Sept. 2 to Sept. 8

Lee Tang-hua (李棠華) recalls performing with his acrobatic troupe on an Republic of China (ROC) Navy warship in the Taiwan Strait. It was the early 1950s, and clashes between China and Taiwan were still frequent. Suddenly, People’s Liberation Army fighters appeared in the sky.

As the rest of the fleet set out for battle, Lee’s troupe remained on the main vessel and continued on with their show.

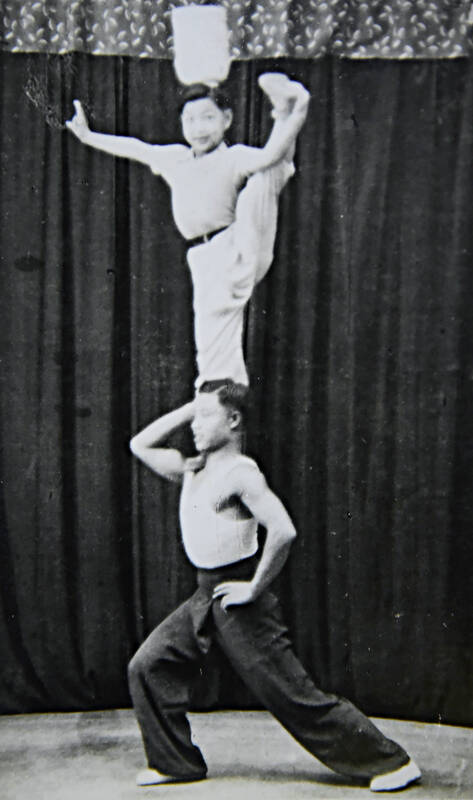

Photo courtesy of New Image Acrobatic Group

Several years later, the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1958 broke out, and the military was having trouble finding people to entertain the troops defending Kinmen, which was under heavy bombardment.

Lee immediately canceled his troupe’s activities in Southeast Asia and flew straight to the frontlines.

People soon began calling Lee the “patriotic performer” (愛國藝人). In the ensuing decades, Lee’s group traveled to more than 30 countries on behalf of the government to rally overseas Chinese support and raise awareness for Taiwan. This was almost as dangerous as visiting a war zone, as Beijing’s agents tried to sabotage their efforts, once even planting a bomb in the theater.

Photo courtesy of New Image Acrobatic Group

Domestically, his high-flying, colorful stunts were frequently seen at public functions, dazzling generations of children from the 1950s to the 1980s.

“Countless Taiwanese knew about acrobatics because of Lee Tang-hua, and countless foreigners knew about Taiwan because of Lee Tang-hua,” a Chinese Television Service (CTS, 華視) presenter said in a special segment aired after Lee’s death on Sept. 7, 2016.

BORN PERFORMER

Photo: CNA

Lee was born in Hunan, China in 1926 and raised in Hankou. At that time, acrobatic troupes consisted mostly of poor children whose families couldn’t afford to take care of them. Lee’s parents, however, were wealthy and even owned one of the local theaters. Around the age of eight, a troupe performed at their theater, and Lee was mesmerized.

He begged his grandfather to let him join, and finally his family relented and sent him to Shanghai to learn under Pan Yu-hsi (潘玉喜). Lee took the stage after a year or two of grueling training, and got his first taste of overseas touring in New Zealand, Australia and the Philippines.

Lee struck out on his own at the age of 16, and returned to Shanghai in 1945 where they found great success. Signature stunts included balancing with one hand on top of nine hapahzardly stacked chairs, riding a bicycle with 10 people, jumping through fire hoops and swallowing swords.

Photo: CNA

Then-president Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) sons Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) and Chiang Wei-kuo (蔣緯國) were both fans, often inviting him to perform at official functions, writes Kuo Hsien-wei (郭憲偉) and Hsu Yuan-min (徐元民) in “History, body: Taking Lee Tang-hua’s acrobatics group as a narrative center” (歷史,身體:以李棠華技術團為論述中心).

When the Chinese communists captured Shanghai, Lee took his family and about 40 troupe members to Taiwan where they hit the ground running with his connections. They began entertaining troops on various frontlines such as Kinmen and Matsu in 1951, and their overseas missions started in 1953.

THREATS AND SABOTAGE

Kuo and Hsu write that it was evident the acrobatics scene was strongly controlled by the government, and performers bore the responsibility whether they liked it or not to further the nation’s political goals.

Lee seemed to enjoy it, however, insisting on hanging the ROC flag everywhere he went, sometimes even outside his hotel. This often drew the ire of those loyal to the People’s Republic of China.

In 1957, the troupe was performing in Bangkok when two burly men appeared and demanded that they remove the flag from the stage’s backdrop. Lee staunchly replied, “Your threats will not work on us!”

However, the theater manager asked him not to hang the flag for the following day’s performance. Lee said he’d rather not perform in that case, canceling the remaining shows at the venue.

Sabotaging methods by enemy agents varied, ranging from stealing equipment to life-threatening violence. One time, communist sympathizers in Indonesia cut one of the troupe’s wires, almost causing a serious accident. Another time they set off firecrackers and told security it was bombs.

Upon landing, the troupe would head first to the local ROC embassy to ensure their safety. On one occasion the embassy staff heard wind that enemy agents had planted bombs in the theater, causing them to abruptly cancel the show.

Beijing even tried to recruit Lee several times with lucrative offers, but he always turned them down.

The bomb threat did not deter Lee, who once said on television, “As performers, it brings us great comfort to be able to do something meaningful for the nation.”

NURTURING TALENT

In the 1970s, Beijing began sending its own acrobatic troupes overseas to raise its international profile.

Taiwan’s diplomatic clout had all but hit rock bottom at this point, so the government formed the “Chinese Acrobats of Taiwan” in 1973 as a countermeasure. It was made up of three notable acrobatic troupes, including Lee’s, as well as other top talents.

From Aug. 20 to Nov. 28, they performed 120 shows in Central and South America and the Caribbean, drawing an average of 4,000 spectators per show.

In 1978, Lee started the Chinese Folk Arts Training Center (中華民俗技藝訓練中心) with partial government support, initially recruiting 60 students between the ages of 8 and 14 in order to keep the art form alive.

Gone were the old days where the disciple lived with the troupe and served the master while watching and learning. Lee took a strict but more comprehensive, systematic approach that focused on providing a holistic understanding of how the stunts worked. He believed that this would increase student interest and also keep them from unnecessary injuries.

In 1990, the training center closed due to lack of funding. The government had already set up traditional performing arts schools such as the National Fu Hsing Dramatic Arts Academy (precursor to National Taiwan College of Performing Arts), which absorbed the training center. Lee’s son disbanded his troupe in 1996, and Lee could only accept that times were changing.

“Because of the grueling training, not many parents would like to send their children to acrobatics school,” he said in 2011. “[This] has caused a succession crisis, while acrobats in foreign countries continue to perform at local circuses and in other countries around the world.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

When nature calls, Masana Izawa has followed the same routine for more than 50 years: heading out to the woods in Japan, dropping his pants and doing as bears do. “We survive by eating other living things. But you can give faeces back to nature so that organisms in the soil can decompose them,” the 74-year-old said. “This means you are giving life back. What could be a more sublime act?” “Fundo-shi” (“poop-soil master”) Izawa is something of a celebrity in Japan, publishing books, delivering lectures and appearing in a documentary. People flock to his “Poopland” and centuries-old wooden “Fundo-an” (“poop-soil house”) in

Jan 13 to Jan 19 Yang Jen-huang (楊仁煌) recalls being slapped by his father when he asked about their Sakizaya heritage, telling him to never mention it otherwise they’ll be killed. “Only then did I start learning about the Karewan Incident,” he tells Mayaw Kilang in “The social culture and ethnic identification of the Sakizaya” (撒奇萊雅族的社會文化與民族認定). “Many of our elders are reluctant to call themselves Sakizaya, and are accustomed to living in Amis (Pangcah) society. Therefore, it’s up to the younger generation to push for official recognition, because there’s still a taboo with the older people.” Although the Sakizaya became Taiwan’s 13th

For anyone on board the train looking out the window, it must have been a strange sight. The same foreigner stood outside waving at them four different times within ten minutes, three times on the left and once on the right, his face getting redder and sweatier each time. At this unique location, it’s actually possible to beat the train up the mountain on foot, though only with extreme effort. For the average hiker, the Dulishan Trail is still a great place to get some exercise and see the train — at least once — as it makes its way

Earlier this month, a Hong Kong ship, Shunxin-39, was identified as the ship that had cut telecom cables on the seabed north of Keelung. The ship, owned out of Hong Kong and variously described as registered in Cameroon (as Shunxin-39) and Tanzania (as Xinshun-39), was originally People’s Republic of China (PRC)-flagged, but changed registries in 2024, according to Maritime Executive magazine. The Financial Times published tracking data for the ship showing it crossing a number of undersea cables off northern Taiwan over the course of several days. The intent was clear. Shunxin-39, which according to the Taiwan Coast Guard was crewed