Aug. 26 to Sept. 1

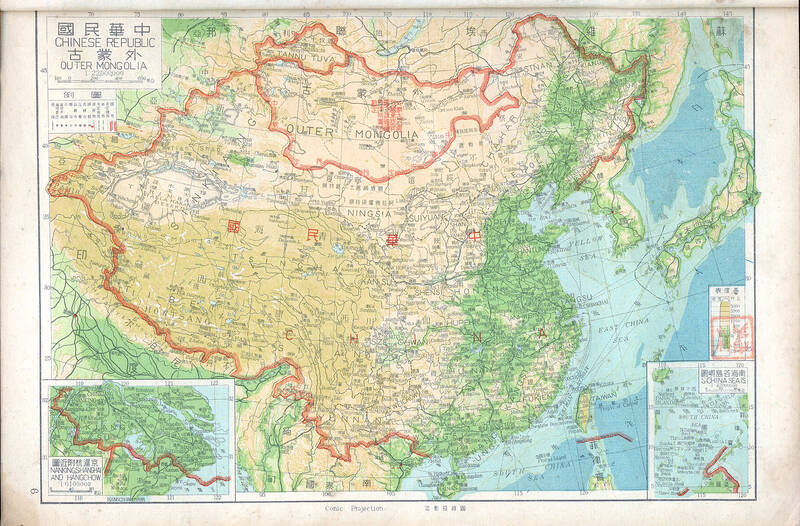

The Republic of China (represented by Taiwan) invoked its Security Council veto just once during its 26 years in the UN: against the Mongolian People’s Republic’s bid to join the world organization in December 1955.

Many considered the socialist nation a puppet state of the Soviet Union, but for Taiwan the issue was more fundamental. At that time, the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) not only held onto its claim as the rightful ruler of China, but considered itself as a successor to all of the Qing Dynasty’s former lands, which included “Outer Mongolia.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The loss of China could be seen as an internal issue resulting from the Chinese Civil War, but the fact was that Mongolia had been independent since 1924. The KMT even acknowledged this fact in 1945 until rescinding its recognition in 1953 due to the voiding of the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance.

From then on, Taiwanese children were taught that the shape of the “motherland” of China resembled a begonia leaf. But in reality, the People’s Republic of China recognized Mongolia after its establishment in 1949, and their version of the Chinese map resembled a rooster. Nevertheless, Mongolia was admitted to the UN in 1961. By the early 1990s when the “Outer Mongolian question” heated up, Mongolia had transitioned into a democracy and enjoyed diplomatic ties with around 100 nations, while Taiwan had dropped out of the UN and only had about 30 allies left.

What complicated the issue is that the current constitution was adopted on Dec. 25, 1946, when the KMT did recognize Mongolian independence. Unlike previous iterations, this document did not specify the scope of ROC territory, only mentioning “existing national boundaries” that were open to interpretation.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

OUTER MONGOLIA?

“Outer Mongolia,” which roughly corresponds to today’s Mongolia plus Russia’s Tuva Republic, fell under Qing Dynasty control in 1691 and remained part of the empire until its demise in 1911. Even though Mongolia declared independence then, the ROC claimed to have inherited the entirety of Qing territory per the Provisional Constitution promulgated in March 1912.

In 1915, Mongolia, China and Russia signed the Treaty of Kyakhta, which made Mongolia an autonomous state of the ROC. The state, however, remained stuck in a power struggle between its two behemoth neighbors, and in 1924, with the help of the Soviet Union, Mongolia broke free of Chinese rule.

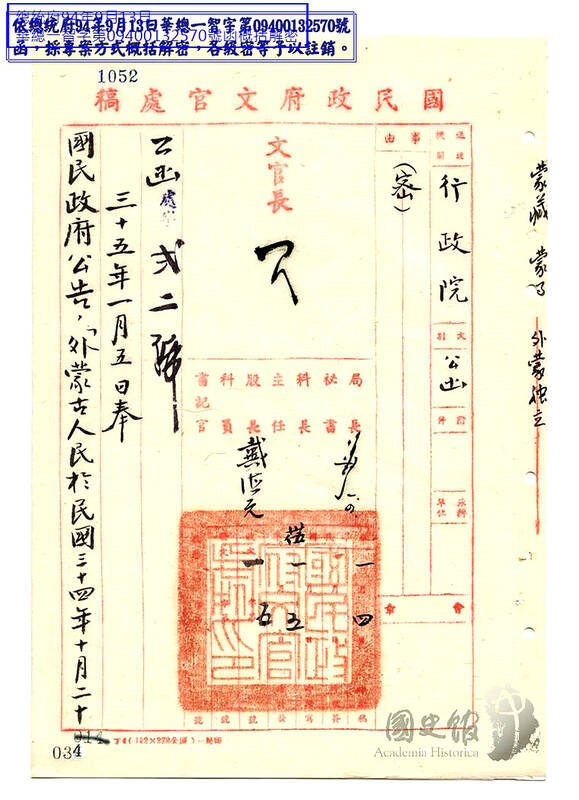

Photo courtesy of Academia Historica

Even so, further iterations of the ROC constitution continued to claim Outer Mongolia as an inalienable part of the nation’s territory, wrote Liu Hsueh-tao (劉學銚) of the now defunct Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission in the 1997 article, “Examining the Outer Mongolia problem from a legal and political standpoint” (從法律政治層面看外蒙古問題).

“Although the nation did not exercise de facto rule over Outer Mongolia, this claim had to be covered in the constitution to serve as justification for future reclamation and to educate citizens to be vigilant and strive toward this goal,” he wrote.

In 1945, the ROC signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, where it recognized Mongolian independence in exchange for the Soviets promising not to help the Chinese Communist Party nor interfere with Xinjiang affairs. Official maps printed during this time excluded Outer Mongolia.

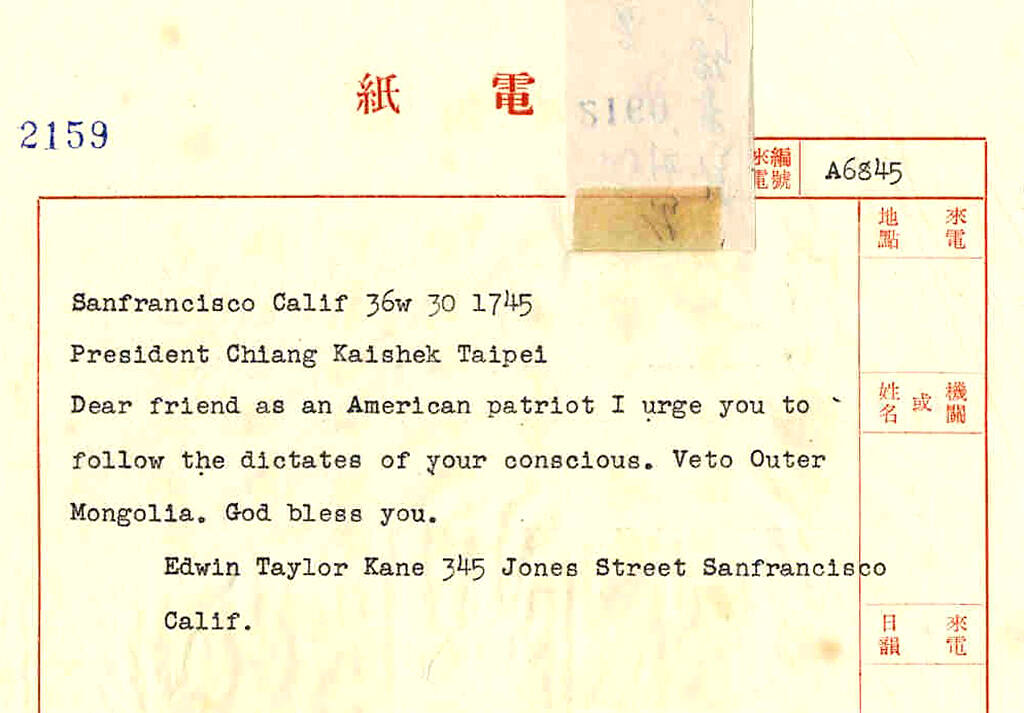

Photo courtesy of Academia Historica

BLOCKING RECOGNITION

Liu “painfully” acknowledged the fact that the ROC had relinquished its claim on Outer Mongolia when the current constitution was drafted, but added that it was only under international pressure during a chaotic time.

He surmised that the 1946 constitution intentionally avoided explicitly defining the nation’s boundaries, and the use of “existing” instead of “current” national boundaries should refer to the ones the ROC inherited from the Qing, which “naturally should include Outer Mongolia.”

In 1952, a UN report found that the Soviets had violated the treaty by aiding the Chinese communists during the Chinese Civil War, which the KMT lost. In response, the KMT rescinded its recognition of Mongolian independence and continued to claim Outer Mongolia for the next 50 years, reverting to the begonia leaf map.

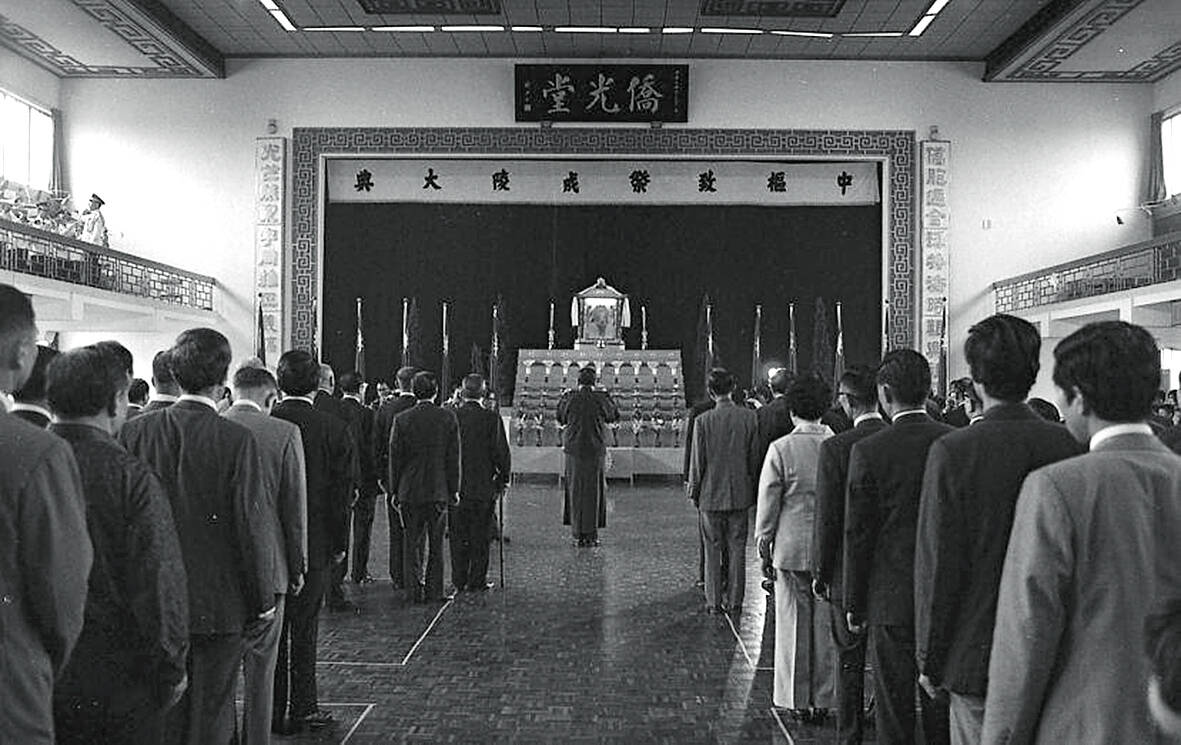

Due to this unwavering insistence, Taiwan spoke strongly against Mongolia’s bid to enter the UN. In 1961, president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) told Life magazine, “We would not hesitate to bar the Chinese Communists and Outer Mongolia at any cost.”

However, under US and Soviet pressure, Mongolia was admitted that October, with Taiwan abstaining from voting. The government continued to balk when other nations established ties with Mongolia — after Australia and Greece did so in March 1967, deputy foreign minister Yang Hsi-kun (楊西崑) warned other allies against following suit, reiterating that Mongolia is “part of our territory.”

Japanese deputy foreign minister Takeso Shimoda was asked about the issue when he visited Taiwan that month, and he promised that Japan would not take any action before consulting the KMT first. Things changed in 1972 following Taiwan’s 1971 exit from the UN (a move which Mongolia supported). Japan established diplomatic relations with Mongolia in February and broke ties with Taiwan in September in favor of China.

QUESTIONING THE CLAIM

After the lifting of martial law in 1987, opposition politicians began questioning the government’s continued claim over both China and Mongolia.

In 1993, Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) legislator Chen Wan-chen (陳婉真) and 18 others requested a constitutional interpretation over the “existing national boundaries” clause. Chen et al argued that since the constitution states ROC territory “shall not be altered except by resolution of the National Assembly,” the 1953 “re-claiming” of Mongolia was invalid since it did not go through said process.

However, the Council of Grand Justices declined to interpret on grounds that it was a political issue rather than a legal one.

In his 1997 article, Liu insisted that there were no direct political and economic benefits to recognizing Mongolia’s independence at the moment, in fact doing so would even affect the ROC’s morale toward reclaiming China and further affect its diminishing international clout.

“There’s no need to rush to a decision about Outer Mongolia until China is reunited,” he concluded.

Under the mayorship of the DPP’s Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) in 1997, Taipei became sister cities with Mongolian capital Ulaabaatar, a relationship usually between two countries. Chen won the presidency in 2000, and in January 2002, the government dropped “Outer Mongolia” from the Statute Governing the Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (兩岸人民關係條例).

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs further announced its recognition of Mongolia that July, noting that “the independence of Outer Mongolia has been a longstanding fact, we are merely respecting this international political reality.”

On Sept 1, 2002, Mongolia and Taiwan established representative offices in each other’s capitals. The Ministry of Interior ceased to print the begonia map that year and textbooks began showing the rooster map in 2004.

The begonia map continues to be used in certain official capacities — for example, several military branches, such as the ROC Marine Corps, continue to feature it in their insignias.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,