Aug. 19 to Aug. 25

The situation was getting increasingly dire for the indigenous Mrqwang and Mknazi Atayal living near Hsinchu County’s Lidong Mountain (李崠山). Largely left alone during the first decade of Japanese colonization, they watched as their northern brethren fell one by one under the aggressive leadership of governor-general Samata Sakuma, who assumed the position in 1906.

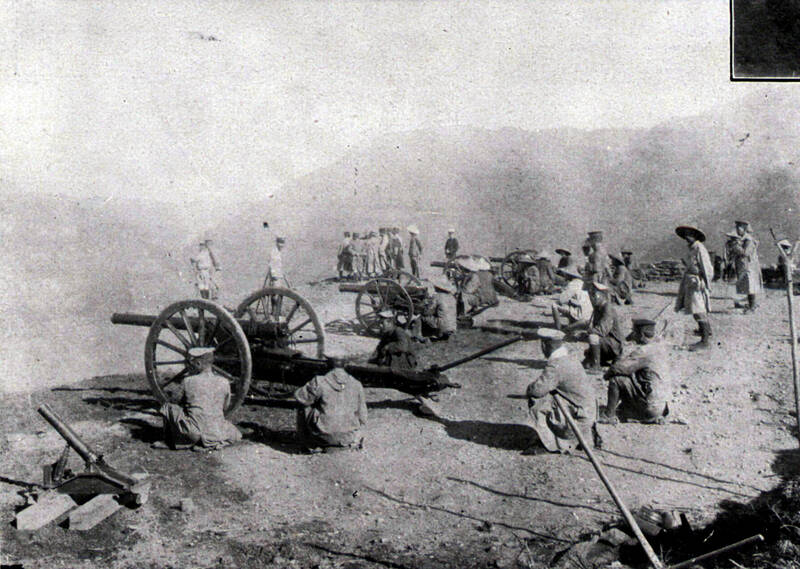

In late 1910, the Japanese defeated their close allies, the Mkgogan, and although the Mrqwang and Mknazi managed to repel an invasion the following year, the Japanese constructed frontier defenses and three hilltop fortresses with cannons aimed directly at their villages.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

After a powerful typhoon in August 1912 devastated Japanese frontline infrastructure and equipment, the Atayal struck back. They launched a coordinated attack on a 10km-stretch of the defense line, seizing one of the forts and pushing the cannons into the ravine. They then destroyed the remaining structures and set the gunpowder on fire, the loud explosions ringing through the ravines.

The win was short-lived as Japanese reinforcements soon arrived. By July 1913, the colonizers had full control over the region, ending the series of conflicts involving at least five Atayal groups now known as the Lidongshan Incident (李崠山事件, also known as the Tapung Incident).

It was the final stand for the northern Atayal, who were forcefully relocated so the government could exploit the region’s valuable timber and camphor.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

COVETED MOUNTAIN

Like the Qing Dynasty, the Japanese did not have full control over the mountainous indigenous areas. Sakuma, however, vowed to change that.

With superior numbers and firepower, the Japanese first targeted Atayal groups living in the southern part of today’s New Taipei City and eastern Taoyuan, prevailing in 1908 after a bloody two-year campaign.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

But Sakuma was not satisfied. In April 1910, he announced the “five year plan to govern the savages,” which aimed to bring every independent indigenous group in Taiwan under government control.

Ethnologist Daya Dakasi (better known as Kuan Da-wei, 官大偉) details the Tapung Incident in his 2019 book Zyaw pinttriqan nqu llingay Tapung (李崠山事件).

The term “Tapung” refers to branches snapping under thick snow. The traditional territory of the Mrqwang, Mknazi and Mkgogan met in this area, and the three enjoyed a close relationship, often banding together to resist invaders.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

The Japanese wanted Lidong Mountain not just for its trees. Camphor harvesters from Yilan, Taoyuan and Hsinchu all had to pass through the area, where they were often attacked by the Atayal who wanted to stem their encroachment. As the highest local point at 1,913m, the Japanese could set up artillery batteries at the top to keep the surrounding villages in line.

“The Japanese attacked the Atayal to seize our land, to fell our trees,” Paqiy Village resident Liu Jen-ching (劉仁青) tells Daya Dakasi. “Without land and without trees, there would be no more Atayal. Of course our ancestors had to fight.”

ASSAULTS ON TAPUNG

The 1,000-strong Mkgogan were partially subdued in previous conflicts, but many continued to fight, fleeing beyond the defense lines and attacking frontier guards, police stations and road workers.

The Japanese decided to deal with them first. To prevent allies from coming to their aid, they closed in from two sides in May 1910. A contingent of about 3,000 troops from Yilan focused on the Mkgogan, while a force of 1,200 from Hsinchu dealt with the Siakaro and Maibarai. The Hsinchu brigade achieved its objective within a month, but the Yilan brigade was having trouble. The Japanese sent reinforcements from Hsinchu, but they were attacked en route by the Mrqwang. The Atayal resistance was fierce, but by September, the Japanese had seized the saddle area of Lidong Mountain.

The tide turned as 1,300 more troops arrived from Taoyuan, and in late October, the Japanese held a surrendering ceremony, where the Mkgogan handed over their firearms. They called for the Mrqwang and Mknazi to do the same, but the two had agreed to refuse and continue fighting.

The Japanese set up a fort and battery on Balung Mountain, from where they could fire at all three groups. Meanwhile, the Mrqwang and Mknazi launched sporadic attacks throughout the year.

On Aug. 2, 1911, a force of over 2,000 made its way toward Lidong Mountain. One contingent successfully took the peak and began constructing fortifications, but the others struggled as the Mkgogan sent warriors to help despite their previous surrender. The Japanese repeatedly tried to rush up the peak, but the Atayal ambushed them from above and engaged them in hand-to-hand combat. Only a handful of Japanese made it to the top.

The Japanese were further hampered by inclement weather, which knocked out their telecommunication lines. The fighting concluded in November, and although the Japanese failed to subjugate either group, they built three mountaintop batteries that would greatly aid their future operations.

FINAL PHASE

The 1912 Atayal offensive was successful at first, but they were driven back behind the defense line on Oct. 1.

The Japanese pushed forward on Oct. 3, but by this time the Atayal had learned a thing or two from their enemy as they began building similar mountaintop fortifications. This battle lasted until Dec. 13, concluding with the surrender of the Mrqwang. The Japanese then expanded the forts on Balung and Lidong mountains and added several smaller ones on the nearby hills.

Only the Mknazi remained, numbering around 630. The Japanese struck on June 25, 1913 with a 2,780-strong force, but they struggled against the much smaller Atayal resistance. On July 7, Sakuma personally arrived at the battlefield, setting up command headquarters at Tapung Fort (formerly known as the Lidong Moutain Fort).

Around this time, the Mknazi fighters multiplied in number — their close relatives, the previously surrendered Siakaro, had sent help. But the Japanese called for even more help, and by July 17, the Atayal began surrendering and turning in their firearms.

After the war, the Japanese sought to erode the ties between the groups. In one instance, they took advantage of a hunting grounds dispute between the Mrqwang and Mknazi, supplying them with guns to widen the conflict before stepping in as mediator. They also relocated the villages to lower ground and encouraged them to farm rice, greatly altering their lifestyle.

Today, Lidong Mountain is popular among hikers, listed among Taiwan’s “Small 100 Peaks” (小百岳) under 3,000m. The Tapung Fort still stands today and became a historic relic in 2003.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the