Last spring, Donald Trump was arrested and arraigned for hush-money payments made to the adult film star Stormy Daniels. For a popular online content creator who goes by the moniker Sneako, the moment seemed to crystallize all of his dark thoughts about America and its coming election.

“Nobody is surprised that Trump was arrested,” he tweeted. “Everybody on both sides knows it’s rigged.”

Sneako, 25, whose real name is Nico Kenn De Balinthazy, had been chasing online fame since he was a teen, first with apolitical gaming videos and slightly wooden man-on-the-street interviews, often about dating, before working briefly for the wildly successful YouTuber MrBeast.

Photo: AFP

In 2015, when he was 16 or 17, Sneako tweeted: “Still need to wrap my head around the fact that I’ll be voting for the next US president.”

The following year, he was particularly excited about the senator Bernie Sanders’s presidential run. But when Sanders lost the 2016 Democratic primaries, Sneako began tweeting about his disillusionment with the political process and announced that he’d be voting for Trump. By 2020, he’d grown even more frustrated: “You can’t convince me that voting matters anymore.”

Sneako, who has Haitian and Filipino ancestry, worked with the white nationalist Nick Fuentes on Ye’s short-lived 2024 presidential run.

Photo: AFP

As Sneako’s frustration grew, his online content shifted from light-hearted entertainment to misogyny, praise for Hitler and antisemitic jokes. Last year, a striking moment between Sneako and his fans — he has thousands of followers on X and Rumble, but has been banned from YouTube and TikTok — went viral: a group of tween boys began gushing misogynistic, transphobic and anti-gay sentiments upon meeting their idol at a Miami Marlins game, seeming to shock even Sneako himself.

Trump’s first arrest was the summit of a long mountain Sneako had been climbing for years; when he got to the top, he’d stepped into a political worldview that was equal parts deeply conservative and bitterly jaded.

Sneako is part of a movement called “the heterodoxy” (from the Greek heteros, meaning “other,” and doxa, meaning “opinion”). Heterodox stars believe themselves to be free thinkers, yet they have a remarkable amount in common. As the journalist Radley Balko explained, they “bill themselves as skeptics who are immune to the trappings of tribalism, partisanship, and the status quo” but they share a suspicion of “elites,” “experts” and “wokeism.” The podcasters, streamers, Substack writers and other content-makers in the heterodoxy are overwhelmingly charismatic, brash, spotlight-hungry men. Their political views could once have been described as libertarian. They claim they are at war with the mainstream media, as well as broadly accepted ideas about science, health and government.

Photo: AFP

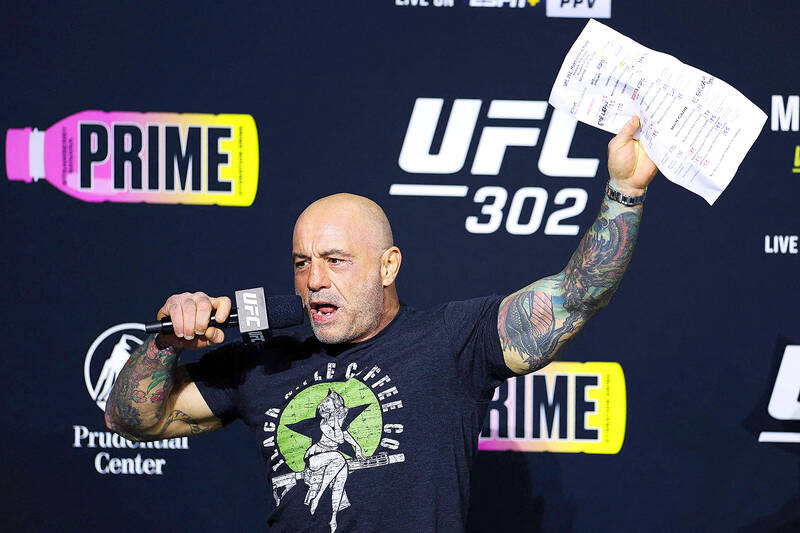

Young men are hooked on the heterodoxy. Joe Rogan, for instance, the most popular podcaster in the world, has an audience that is 81 percent male and more than half 18 to 34-year-olds, according to a YouGov poll of Britons; The Joe Rogan Experience has 14.5 million followers on Spotify.

As a high-stakes election approaches, the heterodoxy is advising listeners that Trump is the lesser of two evils. They’re flirting with the idea of Robert F Kennedy Jr, too. Either way, they didn’t want their listeners voting for Biden, and they view Kamala Harris’s Democratic nomination as little short of a coup.

“Many of the creators stoking fervor by constantly bashing DEI, critical race theory, feminism and LGTBQ+ rights don’t have anything to lose under a second Trump presidency. For the most part, they’re already wealthy and will only financially gain from the tax cuts that will be passed,” said Derek Beres, co-host of the podcast Conspirituality, which looks at the overlap between New Age and far-right beliefs. “This is the very privilege they rail against on a daily basis, and they’re completely blind to it.”

The heterodoxy’s conservative message is not easily squared with its anti-establishment, nihilistic tone. Now, the big question is whether its rightward turn will have young men immersed in this ecosystem more likely to vote Republican as directed — or less likely to vote at all.

YOUNG MEN AND THEIR DISCONTENTS

Heterodox stars are sympathetic to the challenges of being a young man and happy to provide antidotes to discontents. Those come in the form of health and wellness tips (heavy on protein, raw meat and weightlifting), and pseudo-academic, resentment-tinged explanations as to why so many young men are falling behind in higher education and the workplace (feminism, they theorize, is a toxic force that makes men into pariahs). Young men — from new voters to Zoomers like Sneako who filled out their first ballots in 2016 — are looking for purpose in both ideology and life, and these stars spoon-feed it to them, free of charge.

In a year marked by chaos foreign and domestic — war, economic instability and a bitter partisan divide — some data shows these young men sliding away from liberalism into disillusionment. What luck that their favorite podcasters and streamers are on a parallel journey.

Rogan was an actor, UFC commentator, and genial host of the gross-out game show Fear Factor before launching his podcast in 2009. He soon became infamous for platforming noxious figures like the conspiracy-theory kingpin Alex Jones and the far-right commentator Steven Crowder, as well as for using slurs to refer to Black people and anti-LGBTQ+ language. It was a huge controversy when Spotify acquired the podcast on which Rogan would promote election fraud conspiracy theories, and, later, false beliefs about the Jan. 6 riots being secretly instigated by the FBI.

But Rogan also featured the likes of Robert Downey Jr and the science superstar Neil DeGrasse Tyson. Before the 2020 election, he informally endorsed Bernie Sanders, prompting the New York Times to declare that he could “bolster the candidate particularly among the legions of disaffected male voters who have long been critical to his chances to win.” In 2022, Rogan insisted that he was a “bleeding heart liberal” on some issues, and defended abortion rights in a debate with the CEO of the rightwing satire Web site the Babylon Bee, citing the rights of his teenage daughter.

By January of this year, though, Rogan was claiming to no longer be liberal.

“I was 100 percent a left-leaning person who lived in Los Angeles,” he said in comments that were celebrated on the right — but once he moved to Austin, Texas, he rejected what he called “this fake world of leftist ideology.”

Others followed suit. The elfin, motor-mouthed British actor and comedian Russell Brand tried for a second act as a self-help guru before settling into a third role as a YouTube contrarian. He, too, said that he had moved away from identifying as a progressive.

“I think the left is about censorship and centralized authoritarianism, corporatism and globalism.”

He, too, lives in a country that had a transformative election this year, but he has spent more time focused on the US race, posing with the right-wing politicians Ron Johnson and Marjorie Taylor Greene at the Republican national convention and hobnobbing with the likes of the far-right activist Jack Posobiec.

As immune to partisanship as these heterodox stars claim to be, some of their views have calcified into standard-issue right and far-right beliefs. They have vilified trans people and immigrants and spread COVID misinformation. In a recent conversation with Jordan Peterson, the Canadian psychologist turned manosphere personality, Elon Musk misgendered his estranged trans daughter and said she had been “killed” by the “woke mind virus,” which he has previously described as an existential threat to civilization. Musk has also amplified extreme claims about migrants and illegal immigration (most recently in reference to the UK riots, earning sharp pushback from Keir Starmer, the prime minister). Forty-five percent of young men “like and trust” Musk’s views, according to a new survey from the Young Men Research Initiative.

RELIGION

Christianity and “traditional values” have won over some of these supposedly anti-establishment personalities, too — values that can be appealing to young men for their sense of moral clarity (and, perhaps, because traditional gender roles tend to enshrine men as the leaders of their homes). Their anti-trans and anti-gay sentiments, for instance, are often couched in an admiration for what they call “normal” gender roles and presentations, or a rebellion against “wokeness,” which they claim is warping society.

In a conversation with the NFL star Aaron Rodgers, Rogan referred to the guidelines handed down by religion as “laws to adhere to that will make for a much better life for all humans and all life on Earth.” (Rodgers is himself increasingly part of the heterodoxy, denouncing the “woke mob” and repeating false claims about HIV and Aids drawn from Kennedy). Brand, fresh off a bruising sexual assault scandal and still under investigation by UK police, has undertaken what one Christian publication skeptically referred to as a “sort-of conversion.”

“No one trusts the government,” Brand posted after his baptism. “No one trusts the media. So why are we surprised that more and more of us are turning to God?”

It’s this point especially — distrust — about which the heterodoxy are now singing essentially the same tune.

In April, Rogan and the disgraced ex-Fox News personality Tucker Carlson echoed what Sneako feared: that democracy is dead.

“Whenever you have unelected people who are not accountable to anyone making the biggest decisions, you don’t have a democracy,” Carlson proclaimed, referring to unelected federal employees like those working in intelligence agencies, who he claimed secretly control the entire political apparatus. “I would call it tyranny.”

Rogan, in the midst of his political transformation, nodded in agreement.

To hear heterodoxy figures tell it, the government is captured by a secret cabal, and participating in the system is pointless. It’s on them, they believe, to tell the truth about what they’re witnessing, and they have done so, loudly.

Since he took over X, Musk has promoted election misinformation. The self-proclaimed journalist Tim Pool, who got his start streaming Occupy Wall Street rallies, has claimed that this year’s elections are somehow already rigged. The formerly leftist journalist Matt Taibbi said the same, claiming in a January article that the forthcoming election would be swayed by lawyers working to stop Trump.

“The fix is in,” Taibbi wrote. “To ‘protect democracy,’ democracy is already being canceled.”

The sentiment seems to be international: despite having his own significant legal troubles to attend to, the American-British manosphere influencer and accused human trafficker Andrew Tate has tweeted many times about “illegals” being let into the US to steal elections. Of all the heterodoxy, Tate has a particularly magnetic pull on teenage boys, who view his wealth and perceived success as aspirational.

These figures are painting the political and social establishment of the US, with a broad brush, as a place hopelessly captured by corruption, shadowy plots and an enslavement to wokeness. Many of these conspiracy theories are, of course, also being amplified by Trump himself, who claimed in March that the general elections would be rigged. But, as the Wall Street Journal noted at the time, such remarks jeopardize the Republicans’ effort to get out the vote. And Republicans indeed need young men out and voting for Trump if he has any hope of winning in November.

WILL YOUNG MEN VOTE?

Ostensibly, this turn towards the right by heterodox figures who hold sway over young men would have the Republican party celebrating, promising a flood of impassioned new young voters. But the connection between right-sympathetic politics and Republican votes is less clear than it may seem.

“The attention-capture economy and everything that happens in it doesn’t translate into civic engagement,” Beres said. “It just translates into fervor,” generally for the content creators themselves.

For one thing, heterodox stars haven’t been reliably supporting one party or candidate, especially in recent tumultuous weeks.

After the July 13 assassination attempt on Trump, Musk enthusiastically endorsed him. When Biden dropped out of the race a week later, Brand posted a remarkably long and somewhat incoherent screed on X, excoriating Harris’s rise to Democratic nominee as a “bait n’ switch” that was “offered in lieu of democracy.” (He also seemed to confuse “melanin” with “melatonin” while making what many saw as a racist commentary on her ethnicity.)

Sneako, meanwhile, busy as he was tweeting about “zionist demons” and his disdain for trans people, barely responded to the assassination attempt or Harris’s ascendancy until Saturday, when he tweeted: “Trump lost all his assassination aura by choosing [JD] Vance as VP.” He made his continued disillusionment clear by finishing the tweet: “MAGA :(”.

Pair this inconsistency with a generally jaded view of politics, and young male listeners could hardly be blamed for feeling confused, or opting to stay home on election day.

“It might be too early to know about the voting patterns of these young men,” said Dr Karen Douglas, a professor of social psychology at the University of Kent who studies conspiracy theories and their social consequences. “There’s good reason to believe that if they are attracted to these extreme narratives that involve conspiracy theories, they will also be attracted to other extreme political views.”

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislative caucus convener Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) and some in the deep blue camp seem determined to ensure many of the recall campaigns against their lawmakers succeed. Widely known as the “King of Hualien,” Fu also appears to have become the king of the KMT. In theory, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) outranks him, but Han is supposed to be even-handed in negotiations between party caucuses — the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) says he is not — and Fu has been outright ignoring Han. Party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) isn’t taking the lead on anything while Fu