Aug.12 to Aug.18

Doris Brougham (彭蒙惠) was tempted to leave Taiwan many times over the decades, from her mother’s death to a marriage proposal to a lucrative job offer in Vietnam when she struggled financially.

But it just never felt right. The Christian missionary and pioneering English-language educator believed that it was God’s plan for her to remain here, writes Lee Wen-ju (李文茹) in Brougham’s biography Love is a Lifetime of Persistence (愛是一生的堅持).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After making Taiwan her home for 73 years, Brougham died on Tuesday at the age of 98.

She once said, “When Taiwan withdrew from the UN, I was in Taiwan, during the 921 Earthquake, I was in Taiwan. I’m a Taiwanese, wherever I am, that’s where my heart is, Taiwan is my home.”

But despite this, Brougham remained on a work visa that required annual renewal until restrictions on permanent residency were relaxed in 2002. She was finally granted citizenship last May.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

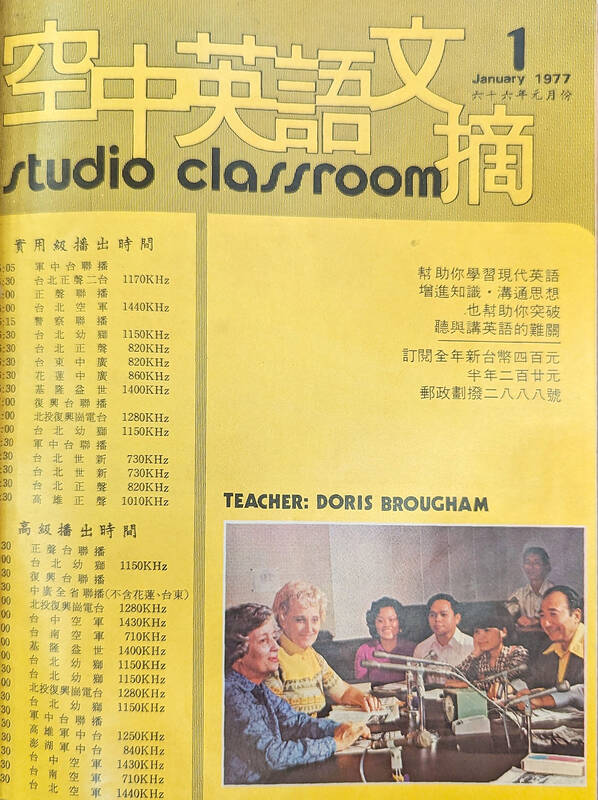

Brougham’s Studio Classroom (空中英語教室) TV / radio programs and magazines, launched in 1963, continue to inspire generations of Taiwanese to learn English in a fun, conversational way.

WARTIME CHINA

Brougham never planned to come to Taiwan; in fact she had barely even heard of China when she first made up her mind as a 12 year old to go evangelize there. Born and raised in the Seattle area in 1936 to a family of modest means with nine children during the Great Depression, Brougham’s opportunities to travel were limited.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While she was attending a Bible summer camp on a scholarship, she heard one of the pastors Andrew Gih (許志文) speak about his homeland and the dangers that Western missionaries faced there. Brougham was especially moved by the story of John and Betty Stam, who were executed by Chinese communists in 1934.

“Who is willing to go to China?” Gih asked after a study session, and Brougham raised her hand. Nobody took her seriously, but she never forgot about it. Years later, the talented horn player gave up a full scholarship to attend the Eastman School of Music in New York, instead enrolling in the Simpson Bible Institute to prepare for missionary work.

Brougham was so determined to go to China that whoever wanted to date her had to have the same plans. While studying Mandarin and Far Eastern Studies at Washington University in 1947, she found a kindred spirit in a man named Jim.

Photo: CNA

However, it just wasn’t a good time to travel there; World War II had just ended and the Chinese Civil War continued ravaging the country. It didn’t matter, however, and Brougham arrived in Shanghai in November 1948 as a member of the Evangelical Alliance Mission.

The situation deteriorated quickly upon her arrival, and the group fled west to Chongqing, Chengdu and finally Lanzhou, where they caught the last plane to Hong Kong in August 1949 just as the People’s Liberation Army descended upon the airport.

BROADCASTING GOD’S WORD

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Brougham spent about a year in the British colony, working with refugees and becoming the only American and female performer in the Hong Kong Orchestra. Rumors flew that the communists were advancing, and the mission planned to relocate its Asia operations to Japan.

Brougham’s Mandarin had greatly improved by then, and she decided that unless she was sent back to the US, she wanted to stay with the Chinese. In December 1950, she headed to Formosa, where there were also Chinese speakers — but ironically, she spent her first seven years in a part of Hualien where locals spoke only Japanese and indigenous languages.

Jim never made it to China, and Brougham never responded to his last letter. Her father and mother both died during this time, but she resisted the urge to return to Seattle. Most missionaries arriving opted for the more populated east coast, but Brougham looked at the map and chose Hualien, where she began teaching at the Yushan Theological College and Seminary. The children learned Mandarin quickly at school, and she was able to communicate through them.

Brougham wanted to spread Christianity to more Taiwanese, and thought radio would be an effective medium. She wrote to the Broadcasting Corporation of China (中廣), who to her surprise immediately agreed to give her a one-hour weekly program.

Recorded with makeshift equipment in her flat, the show included songs, skits, sermons and music. Sometimes, the guests and staff were too busy to show up, and Brougham ended up playing an hour of trumpet; she jokingly called these sessions solo recitals.

The show was well received, and her media career grew rapidly. Around this time, she fell in love with a doctor at the Mennonite Christian Hospital, who asked her to marry him and move back to the US. Brougham wanted a family, but she just could not leave Taiwan. She turned him down, saying she already made a promise to God.

TEACHING ENGLISH

On a fundraising trip back home, Brougham ran into high school friend Leland Haggerty, who was married with four kids and a nice job. Haggerty showed interest in helping out with the venture, but Brougham did not expect him to move to Taiwan with his entire family.

The nation was about to enter the television age with the launch of Taiwan Television (台視, TTV) in 1963. Brougham saw the potential of the new tech and relocated to Taipei so she could work with the station, selling valuable mementos such as her father’s saxophone to fund the move. The 16 staff pooled their resources to make it work, even taking on odd jobs such as cleaning houses and tutoring. Soon they established Overseas Radio and Television (ORTV).

The programs were popular, but money remained tight. Brougham received a high-paying offer from the US government to work with Chinese in Vietnam that could ease their worries, but she felt an inexplicable unease and refused the offer. Instead, she headed to the US and Canada to fundraise.

In 1963, the Ministry of Education commissioned Fu Hsing Broadcasting Station (復興) to produce an English learning program. Brougham saw how Taiwanese struggled with English at the various international conferences she attended, and was happy to help.

On Aug 1, Studio Classroom hit the airwaves. Brougham eschewed the standard “this is a pen” teaching format, instead sharing interesting articles from American magazines and explaining the contents in a casual, conversational manner. It was a huge hit, and per listener request they began publishing a two-page supplement to the show. This grew into a full magazine by 1974.

Chinese writer and translator Lin Yu-tang (林語堂) became a fan of the show after moving to Taiwan in 1966, the two became good friends. He helped further boost the show’s listenership.

Brougham also hosted the “Heavenly Melody” musical program on TTV, the only religious show at that time which drew the ire of other groups. This led to the formation of Taiwan’s first full-time Christian choir that performed original tunes and toured overseas.

Although her goal was still to evangelize, Studio English was Brougham’s best-known venture, not just teaching the language but exposing locals to many new concepts and ideas. Brougham also taught English to China Airlines flight attendants for many years and was personally commissioned by president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) to help top government officials with the language. She was noted for her ability to get these powerful individuals to relax their pride and have fun in class.

Brougham received countless awards for her contribution, including the Order of Brilliant Star, Taiwan’s highest non-military honor.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,