The wreckage of two scooters are just visible from beneath white sheets — the kind that is laid over a deceased body at the scene of an accident.

Intermittently, bright lights are projected onto the sheets. This is the footage from Yang Chia-shin’s (楊佳馨) two motorbike dashcams as she rolled down Keelung Road (基隆路) in Taipei one fateful evening in February, 2022.

The collision is sudden, a 360-degree spin before she is thrown from the vehicle.

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

The perspective change is captured by both cameras, one to the front, one to the rear, as the motorbike careens out of control, until all movement stops.

This dual installation is the main focal point of Return to the Scene (重返現場), a series of artworks on view at Hualien’s Good Underground Art Space (好地下藝術空間), which document Yang’s scooter accident and her slow recovery thereafter.

“I’ve tried to reconstruct the sensitivity of the moment between life and death,” she says.

Photos: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

Yang hasn’t just used video but a range of media and materials to recreate the sensory experience of the accident in the gallery space.

There are growls of motorbike engines revving.

She’s mounted a broken wingmirror on the wall framing a photograph of the point where she came off the road.

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

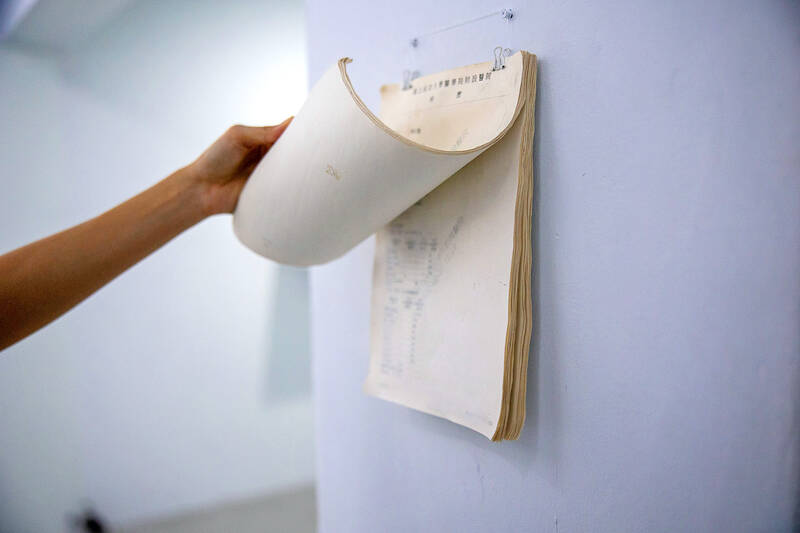

The crash required two collar bone operations and has left her shoulder scared. Yang collected a journal of doctor’s reports in the wake of the accident.

But far from being morbid or depressing, Yang’s work is more a form of exorcism — the artist’s way of working through “emotional layers” with the “aim of cleansing preconceived perceptions and heal her trauma,” as the introduction puts it.

One video shows her cleaning her scooter in an artwork titled The Motorcycle’s Rebirth (機車的重生). “It’s actually me washing away the pain of the past.”

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

“There’s movement in Yang’s work,” says the gallery’s art director Tien Ming-chang (田名璋), adding that there is a unique dynamism, which “invokes a sense of instability.”

The video is projected onto a shroud-like white cloth, which also “serves as a metaphor for the presence of death,” he says.

White symbolizes death, and is associated with the robes worn in traditional funerals.

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

In the wake of the enormous earthquake on April 3, I asked how Tien thinks Hualien residents might react to work that addresses life’s fragility and human mortality.

“Facing natural disasters is not a matter of the last two or three days for Hualien people. It is part of our DNA,” he says.

Although locals have grown accustomed to living on a fault line, he says, “Yang explores issue that we cannot escape,” in her artwork, which he believes, “will help people understand life better as a result.”

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

Photo courtesy of Wu Fang-yi, Good Underground Space

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

This was not supposed to be an election year. The local media is billing it as the “2025 great recall era” (2025大罷免時代) or the “2025 great recall wave” (2025大罷免潮), with many now just shortening it to “great recall.” As of this writing the number of campaigns that have submitted the requisite one percent of eligible voters signatures in legislative districts is 51 — 35 targeting Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus lawmakers and 16 targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers. The pan-green side has more as they started earlier. Many recall campaigns are billing themselves as “Winter Bluebirds” after the “Bluebird Action”

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American