July 29 to Aug. 4

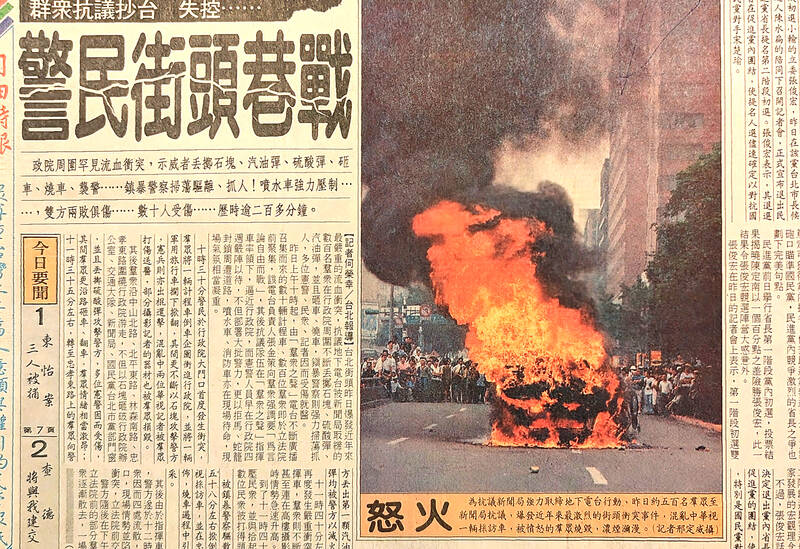

A furious crowd of about 500 people gathered at the Executive Yuan, circling the building while hurling rocks at the windows and police. Yelling, “Lian Chan (連戰, then-premier), come out if you dare, you son of a turtle,” they smashed and overturned surrounding vehicles, and at one point, a taxi tried to ram the main entrance. The demonstrators then started hurling gasoline bombs, clashing with police and setting a Chinese Television Service (華視) van on fire.

Underground radio station Voice of the Masses (群眾之聲), which led the protests, asserted that this was a battle for freedom of speech. Two days earlier, on July 30, 1994, the now-defunct Government Information Office (GIO) raided the offices of 14 underground stations. These stations, which were involved in numerous political rallies during the 1990s, were known to be able to quickly rally the masses — especially taxi drivers — to action.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

Underground radio stations thrived in the early 1990s, a few years after the lifting of martial law when the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) still exercised strict control over non-print media. They were often affiliated with the opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), discussing topics that were ignored in the mainstream media and providing a voice for those who felt oppressed. The defining feature was the call-in hotline, where anyone could speak their mind at length.

About 20 officers and civilians were hospitalized during the protest. Did protesters go too far? A Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister paper) editorial states, “While there is no reason for the government to raid underground stations, there’s also no place in a democratic nation for a radio station to not only command a mass demonstration, but be willing to incite public violence.”

The paper called for the government to open up the airwaves and reduce the hurdles for stations to legalize.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan History

CHAMPION OF CABBIES

The government banned the establishment of new civilian-run radio stations in 1959, and there were 33 legal channels when martial law was lifted. The 13 state or party run stations dominated in both scale and reach. While the newspaper ban was lifted in 1988, no radio station applications had been accepted.

Chen Ching-ho (陳清河) writes in “The changing role of Taiwan’s illegal underground radio stations between 1991-2004” (台灣地下電台角色的變遷 1991-2004) that the first true underground station was Chuan Ming (全民), established in December 1992 by DPP legislative candidate Chang Chun-hung (張俊宏). Since most stations focused on KMT hopefuls, Chang sought other ways to connect with voters.

Photo: File

The station continued after Chang got elected, focusing on a variety of political and social issues. It was an early favorite for taxi drivers, who felt exploited because the government restricted individual licensing, forcing them to join exploitative cab companies, writes Tsai Ching-tung (蔡慶同) in “When cabbies hear the underground radio: A discussion on the relationship between underground radio and social movements” (當運匠聽到地下電台: 論地下電台與社會運動之關係).

In July 1993, Chuan Ming launched a call-in program hosted by A-zhu (阿珠) to discuss public policy. Since A-zhu’s husband was a cabbie, she often criticized the licensing policy and later invited an expert as co-host to explain the technicalities and how they could push back. After several months of on-air discussion, the hosts and 25 drivers formed the Chuan Ming Taxi Association to safeguard their rights. The association grew quickly and was known for its ability to mobilize support, whether it be during disputes or demonstrations. Sometimes the protests turned violent, giving them a bad reputation (see “Taipei’s epic taxi war,” Aug. 14, 2022).

Tsai writes nearly half of the program’s air time was given to listeners to call in, with each caller speaking for an average of six minutes. Almost 90 percent were taxi drivers.

Photo: Hsing Ting-wei, Taipei Times

The government finally opened up a number of new licenses in 1993, although capital, technical and other requirements made it difficult for the mostly bare-bones underground stations to make the cut. Instead, many slots went to corporate stations. Chuan Ming evidently had the money as it used expensive imported equipment, and became legal in October 1994.

FREE-WHEELING DELIVERY

Tsai writes that out of the 50 or so stations that popped up in 1993 and 1994, more than 40 were run by DPP members or supporters. The programming was often in Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), rallying Han Taiwanese who felt oppressed by the KMT.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

Chen writes that some stations simply preferred to remain underground so that they could continue their free-wheeling and provocative programming style. They were also worried that they would lose their supporters once they became part of the system. Most relied on listener funding and peddling illegal medicine.

Most hosts were not professionals; they did not have a “radio voice” and used everyday language. They often got tongue-tied or made errors, and swearing and yelling was common.

“Listeners felt more emboldened to interact with these ‘hosts who didn’t sound like hosts.’ It was like a speaker’s corner at a night market. Anyone could become a ‘’street commentator,’” Chen writes.

It was basically social media before the Internet.

Launched in November 1993 by Hsu Jung-chi (許榮棋), Voice of Taiwan (台灣之聲) took Chuan Min’s call-in formula to the next level, and was even more effective in mobilizing the masses. In addition to call-ins, it also had call-outs and three-way conference calls, directly reaching out to politicians for comment during debates. “For NT$1, you can be the boss” was their slogan.

Taiwan New Telecommunication (寶島新聲, TNT) was started in March 1993 by social activists and DPP members, including former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), who was then a legislator. Besides political commentary, it also supported causes such as indigenous and labor rights.

Other notable early stations include the Voice of the Taiwanese Nation (台灣國之音), which was a Buddhist station that supported independence. It alternated between chanting sutras and criticizing the KMT and also sold tea products. And there was Voice of the New Party (新黨之音), which appeared in 1995 as a rare pro-Republic of China (ROC) station that opposed both the KMT and DPP.

AUTHORITIES CRACK DOWN

In April 1994, cultural workers and the left-wing Masses (群眾) magazine were trying to stop the KMT from demolishing their former central headquarters, which was a historic building. When the government began tearing it down in the small hours of April 11 with police protection, Masses staff quickly called Voice of Taiwan and rallied hundreds of taxicabs to the scene. Things got contentious, and both government property and taxis were damaged.

A week later, the police raided the Voice of Taiwan office and confiscated its equipment — the first time authorities took action against an underground station. After witnessing the power of radio, Masses staff closed the magazine and launched Voice of the Masses. With the Voice of Taiwan temporarily out of commission, Voice of the Masses quickly filled its role.

On July 30, the GIO struck again, hitting 14 underground stations in one morning, injuring Voice of the Masses founder Chang Chin-tse (張金策) and other staff in the process. The station quickly replaced its equipment and resumed broadcasting that night, calling for supporters to surround the Executive Yuan on Aug. 1. The protest quickly turned violent, and the mainstream media branded those from the station as hooligans and instigators.

While authorities continued to suppress underground stations (ironically, Chen Shui-bian went after them especially hard when he was president), they persevered, although their political influence waned as the media environment became increasingly liberal. Several of the oldest stations, including TNT, opted to turn legal as restrictions eased.

Listenership of Voice of the Masses dropped after Taiwan’s first direct presidential elections in 1996, and it shut down in 1998. Voice of Taiwan appears to still exist as an online radio, but its Web site is barely functional and is plastered with life insurance ads, which has long been its main revenue source.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had