To step through the gates of the Lukang Folk Arts Museum (鹿港民俗文物館) is to step back 100 years and experience the opulent side of colonial Taiwan. The beautifully maintained mansion set amid a manicured yard is a prime example of the architecture in vogue among wealthy merchants of the day. To set foot inside the mansion itself is to step even further into the past, into the daily lives of Hokkien settlers under Qing rule in Taiwan. This museum should be on anyone’s must-see list in Lukang (鹿港), whether for its architectural spledor or its cultural value.

The building was commissioned by Lukang native Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮) as a family home in 1913. Already a successful businessman in pre-Japanese Taiwan, he continued to gain prosperity and status after the handover, no doubt aided by his allegiance to the new Japanese rulers. After Japanese troops had captured Keelung and the Republic of Formosa President had fled, it was Koo who opened the gates of Taipei to allow Japanese troops in to establish order. He was subsequently nominated for several official posts, including a position in the Japanese legislature, a first among Taiwanese.

In 1973, Koo’s sons Koo Chen-fu (辜振甫) and Koo Wei-fu (辜偉甫) transformed the mansion into a museum by donating the house and a collection of artifacts, later supplemented by other artifacts from the Koo family and members of the public. The museum has continued to operate up to the present, albeit with several interruptions for restoration work. The carefully selected, high-quality artifacts on display here offer a succinct yet rich overview of life under Qing-ruled Taiwan.

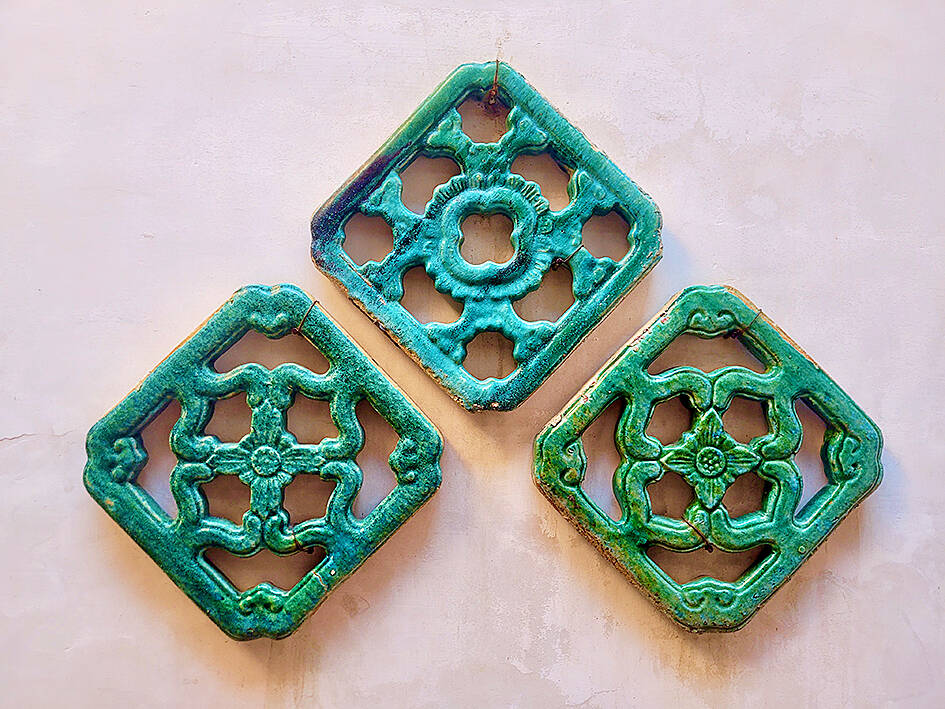

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

AN ARCHITECTURAL FAD

In the early 20th century, many wealthy Taiwanese and overseas Chinese built so-called “Western-style mansions” (洋樓) as both spacious living quarters and symbols of status. These were generally two-story brick buildings with stone accents, often in ornate Baroque style. They sometimes replaced an earlier home, but were sometimes added on to existing Fujian-style dwellings, creating a stark contrast. After the difficult economic times brought on by the war, this style of building fell out of fashion and most of the remaining Western-style mansions in the country are now museums preserved with public funds, or abandoned curiosities slowly deteriorating in the countryside, silent reminders of more prosperous times.

For anyone who appreciates this architectural style, the Lukang Folk Arts Museum is a must-see. The main exhibit hall here, the “Dahe House” (大和大厝), is the most striking example of a Western-style mansion that this author has seen in the country. This is due not so much to the building’s design — which is rivalled or perhaps surpassed by other mansions in Taiwan — but to the immaculate restoration and maintenance carried out on the building and the beautifully manicured grounds surrounding it. As one passes through the gate from the narrow streets of Lukang into the expansive yard, the view of the property is breathtaking.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Dual turrets with black domes flank the main entrance, which boasts Corinthian columns and a red-and-white striped pattern reminiscent of the Presidential Palace. Open-air walkways on both floors with arched openings complete the ornate facade. Attractive paving stone walkways and carefully manicured trees nestled into a spotless green lawn surround the building. Whatever your views on colonialism, it’s hard not to be impressed by the aesthetics of this admittedly very colonial property. Choose a sunny day to visit as the interplay between shadows and light further enhances the crisp geometry of the building.

Off to one side is a more traditional brick building that predates the colonial era, the Ku-Feng Pavilion (古風樓). Unlike the Dahe House, this is a plain brick building with whitewashed interior walls and timber ceilings, just as one can see in traditional three-sided sanheyuan (三合院) dwellings. The first floor is made up of a courtyard and traditional kitchen, while the second floor features a display of two specialized rooms: the nuptial chamber, euphemistically (or perhaps quite literally) termed “hole room” (洞房) in Chinese; and the nursery, including a bed for the new mother and a cradle with mosquito net for the baby.

A WINDOW INTO OLD HOKKIEN CULTURE

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The museum is worth a visit for the architecture alone, but the same could also be said of the artifacts it houses. Through this collection, the Koo family have demonstrated that despite their past association with Japanese colonial powers, they are still fiercely proud of their Hokkien heritage. They have collected and preserved over 6,000 artifacts, displaying just enough of them in the museum to give visitors a broad understanding of the traditional lifestyle of Hokkien settlers in Taiwan, without getting too bogged down in details.

Through simple displays with English and Chinese descriptions, visitors can learn about customs surrounding childbirth, marriage and important festivals. In addition to the fully furnished nuptial room and nursery mentioned above, a few representative items of clothing for important celebrations in excellent condition are on display. Everyday clothing is included in the exhibits, including slippers worn by women who underwent the long-abandoned practice of foot binding. One of the more interesting but obscure artifacts here is an original mold used to make “candy pagodas” — freestanding blocks of sugar in the shape of pagodas or natural objects like flowers and animals — which used to be a common wedding gift to the bride’s family.

The arts are well represented here, too. Sword-swallowing and acrobatics were performed in front of a local temple in the early 1900s, and the actual swords and rings used are on display in the museum. The most popular music styles among Chinese settlers in Qing-era Taiwan were called beiguan (北管) and nanguan (南管). The difference between these two can be imagined after a quick glance at the instruments in their separate display cases. Puppetry — both the glove and the shadow varieties — is represented with a few high-quality exhibits. Painting and calligraphy — art forms for which Lukang was particularly renowned in centuries past — round out this part of the museum.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the