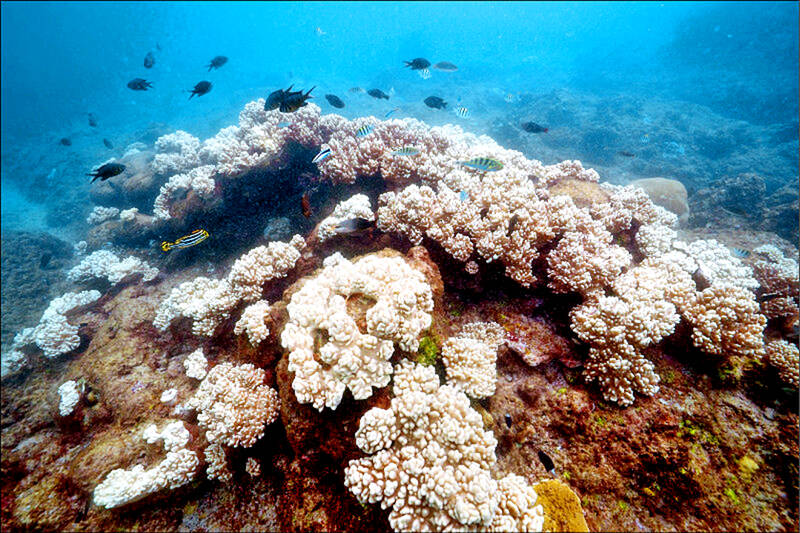

Throughout the world, coral reef ecosystems are withering as a result of climate change and warming oceans. Some of the reefs around Taiwan, such as those close to Pingtung County’s Siaoliouciou Island (小琉球), have already suffered massive and perhaps irreversible damage.

Corals get their color from single-cell photosynthetic organisms called zooxanthellae. If they become stressed by high temperatures or pollution, they expel these zooxanthellae and revert to a stark whiteness. This “bleaching” isn’t necessarily fatal. When the period of stress is brief, the zooxanthellae are often able to return. If it’s prolonged, however, the consequences can be devastating, both for the corals themselves and for the many marine species that shelter and spawn within reefs.

Even where conditions make it possible for a new reef to appear, it takes an eternity: Up to 10,000 years for a typical reef, “while barrier reefs and atolls can take from 100,000 to 30 million years to fully form,” says the Web site of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Photo: Taipei Times file photo

Several of Taiwan’s coral reefs experienced severe bleaching in 2020. The gradual rise in water temperatures wasn’t the only cause. Because there were no typhoons that year, at the height of summer there was less churning of cooler water from the ocean depths.

The extent of the bleaching was obvious, both to specialists such as the Taiwan Coral Bleaching Observation Network and to amateur divers. Among the latter was an engineer working for Taiwan-based manufacturer Delta Electronics Inc. Photos the employee took of bleached corals at Houbihu Fishing Harbor (後壁湖魚港), adjacent to Kenting National Park, inspired staffers at Delta Electronics Foundation (DEF) — a climate-focused NGO established by the company in 1990 — to look into whether existing climate mitigation projects might suggest ways in which humanity can help imperiled coral reefs.

According to emailed responses from the DEF, they soon discovered there was “a great need for cross-sectoral collaborations on coral restoration and research, and that Delta’s technology could play a crucial role.”

Courtesy of Delta Electronics Foundation.

The foundation’s first step was to equip corporate volunteers “with the best-available knowledge of coral ecosystems and restoration.” In 2021, working with marine conservation professionals, Delta converted an abandoned abalone culture pond on Taiwan’s northeast coast into a coral nursery.

Collaborating with the National Museum of Marine Science & Technology (NMMST), Delta last year established the Chaojing Coral Conservation Center within Keelung’s Wanghaixiang Chaojing Bay Resource Conservation Area (望海巷潮境資源保育區). The center is a location for ex-situ conservation work (the breeding and maintenance of endangered organisms under partly or wholly controlled conditions) “prioritizing the conservation of 20 native coral species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Endangered and Vulnerable Coral List,” the DEF says.

The center aims to foster over 10,000 corals within three years. At the same time, Delta volunteers are assisting NMMST scientists to research coral reproduction and heat-resilient coral species cultivation.

Photo courtesy of Orsted

Emphasizing that the DEF makes a long-term commitment to each project it supports, Delta is backing the coral restoration effort with technology, funding and manpower. The coral breeding system is based on the company’s vertical farming technology, and incorporates Delta’s lighting and industrial automation solutions.

“Following collaboration between NMMST scientists and Delta engineers, initial test results showed a 40 to 50 percent increase in growth rates for certain coral species, compared to in-situ samples,” Delta says.

Delta’s micro-computed tomography equipment is being used to generate 3D X-ray images with pixel sizes down to one micrometer. (Human hair is 20 to 40 micrometers in width.) This allows scientists to analyze coral bone density and soft tissue, and to study coral calcification mechanisms and skeleton structure in detail, adding to humanity’s understanding of endangered corals.

Photo courtesy of Orsted

WIND FARM CORAL REEFS?

Among the multinational enterprises involved in Taiwan’s ambitious wind-energy program is Orsted A/S. The Denmark-headquartered company is partnering with the Penghu Fisheries Research Center (a unit of the Ministry of Agriculture’s Fisheries Research Institute) in a human intervention to support coral habitat on the foundations of four turbines within the Greater Changhua offshore wind farms between 35km and 50km from Taiwan’s west coast.

These locations offer stable sea temperatures of 20 to 25 degrees Celsius in which, it’s hoped, corals can thrive. Coral reefs don’t form in deep water because zooxanthellae rely on sunlight for photosynthesis, but — as Orsted’s Web site explains — on designated areas of turbine foundation structure, “corals will have good access to light while being protected from extreme temperatures by the natural circulation of the cooler, deeper water the turbines stand in.”

Orsted’s ReCoral project is still at the proof-of-concept stage, says Lee Chih-an (李之安), the company’s Asia Pacific’s senior sustainability advisor.

The first step was the collection of approximately 200,000 coral eggs as they washed ashore in the Penghu archipelago in the spring of 2022. Lee says that taking even this great number doesn’t undermine the natural reproduction of coral in the ocean, as many species release vast surpluses of gametes.

That summer, 10,000 lab-cultivated coral larvae were shipped out to the turbines and released. As with many first attempts, it wasn’t a great success.

“The results of the 2022 offshore seeding of coral larvae indicate that the water column may be too challenging for coral larvae to compete for living,” says Lee. She adds that, while the ocean’s temperature and salinity were comparable to lab conditions in which the larvae had thrived, “factors such as waves, current and keen competition with other benthic animals like mussels and barnacles” complicated the picture.

In May and June last year, researchers once again went out to gather coral spawn, which they then seeded on brick tiles and cultured in the laboratory at Penghu Fisheries Research Center.

“A thermostatic system and artificial lighting were installed, to keep the corals alive throughout the winter by ensuring the temperature stays close to 23 degrees Celsius. This should make them strong and healthy, and give them a better chance of surviving the offshore environment,” says Lee.

For the next attempt, lab-grown one-year-old and two-year-old corals (the 2022 and last year’s “crops”) will be moved to the wind farm. That is expected to give scientists a better idea as to the location’s suitability for corals, and also yield data that could assist coral restoration efforts in other parts of the world.

Some researchers say the best way to future-proof coral reefs could be through the cultivation of climate-resilient corals. If scientists can bolster corals’ heat tolerance through selective cross-breeding, or by conditioning and acclimating certain species to gradual increases in water temperature, humanity might be able to reduce the severity of bleaching events. Given the importance of reefs to marine biodiversity and fisheries, and their role in mitigating storm surges and land erosion, we should grasp at any straw we see.

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has