After her mother’s death, Elizabeth (not her real name) sought therapy to process the trauma of seeing her father abuse her mother while she was suffering from dementia.

With a lack of therapists on the New South Wales South Coast, she turned to online counseling platform BetterHelp, which claims to “remove the traditional barriers to therapy.”

BetterHelp’s Web site says it provides “affordable and accessible” care, and charges clients US$90 to US$120 a week to talk with a therapist “however you feel comfortable — text, chat, phone, or video … when you need it.”

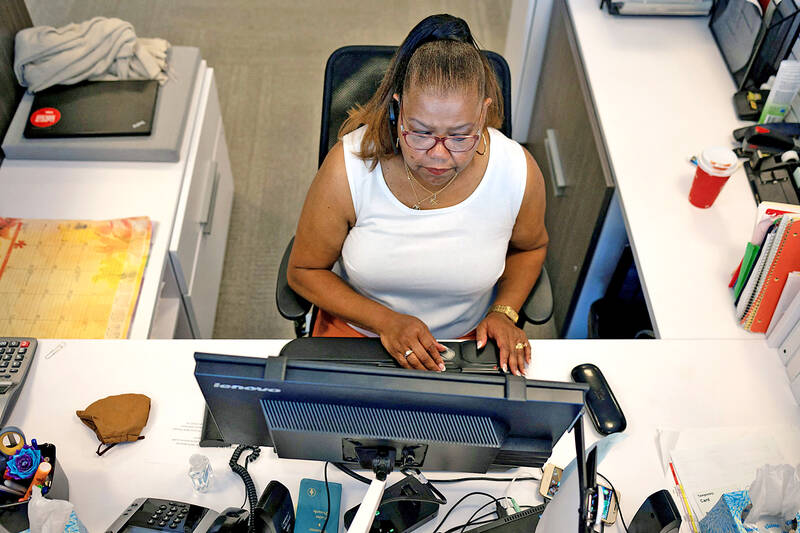

Photo: AP

After matching with a therapist on Feb. 20, Elizabeth was immediately charged a monthly fee of US$296.64, discounting her first week of therapy.

However, she found the only available option — a 30-minute live therapy session — restrictive. During her first consultation, she felt pressure to rush her history, including her own abuse by her father during childhood.

She also hadn’t realized it was a US-based company and she would have to wake up at 3am Australian time to access the group therapy that was on offer.

Photo: Reuters

Elizabeth says she received daily reminders to use the platform’s journaling function but none of what she wrote was forwarded to her therapist. “I was anxious reliving a lot of stuff on a daily basis without getting a solution.”

Elizabeth canceled her subscription because she couldn’t justify US$90 a week during a cost-of-living crisis for a service she said wasn’t helping her.

NOT A CRISIS SERVICE

As BetterHelp looks to expand its Australian operations and customer base, mental health experts are concerned the US company’s subscription model risks creating therapeutic issues. There’s the potential for codependency, they say, and a lack of an endpoint for the therapy.

BetterHelp clients pay a month’s subscription upfront for one hour of a therapist’s time each week that includes either a 30 or 45 minute live session. The remaining time is for the therapist to send messages, emails and worksheets to clients.

Carly Dober, a psychologist and director of the Australian Association of Psychologists, says it is “ethically concerning” that clients are charged a month in advance — irrespective of how many sessions they attend — given mental health issues impact cognition, memory and a person’s ability to work. BetterHelp users also need to actively cancel subscriptions.

Frances Carlton, a clinical counselor who provided therapy sessions on BetterHelp, says the platform advertises itself as an affordable option but clients might be better off seeing someone in private practice when they need to.

While BetterHelp appears cheaper than traditional in-office therapy, clients who attend counseling in-person don’t pay for four weeks upfront “like a gym membership” and don’t have to attend every week to get value for money, Carlton says. Instead, they can choose how often they attend sessions.

Carlton also questions the value clients receive, when 30 or 45 minute live sessions aren’t long enough. She says in private practice she allows at least 75 minutes initially because after 45 minutes a client is just starting to get comfortable. After a few sessions, the therapist can reduce the time to an hour, she argues.

Carlton says while BetterHelp warns it is not a crisis service “the reality is clients get into crisis during sessions because of, sometimes, what they’re talking about.” She says she never sends those clients away when their time is up but under BetterHelp’s model “that’s exactly what you have to do”.

BetterHelp pays therapists US$30 an hour if they work up to five hours in a week. The rate increases by US$5 for every additional five hours worked until those doing a 40-hour week earn US$70 an hour. The platform does not pay overtime and deducts pay if a client logs on late, Carlton says.

Dober says BetterHelp’s rates of pay are below minimum wage under the applicable private sector award but contracting at the platform’s rates is legal.

Carlton says BetterHelp gives clients the illusion that therapists will be messaging every few days and advertises that “you can message your therapist at any time from anywhere”. However, the pay structure does not compensate therapists for that amount of work.

QUALITY OVER QUANTITY

Dober is also concerned BetterHelp requires clinicians to text patients every three days and respond to texts sent by patients within 24 hours and 48 hours on weekends.

“This can create a whole raft of therapeutic issues, such as poor boundaries, codependency, and it can affect the therapeutic relationship if the client perceives feeling forgotten or not important if realistic and supportive communication timeline expectations are not managed at the outset,” Dober says.

Associate Prof Andrew Campbell, a psychologist and the chair of the Cyberpsychology Research Group at the University of Sydney, says if the model of care is “too enmeshed” clients may believe their counselor can help them solve every problem. Campbell is also concerned about a lack of so-called exit points.

“There’s a question about enabling; is the model set up for an exit point where the person is not going to use the app any more because they’re feeling better? Or is it set up to be quite enmeshed where they feel ‘I’m going to build a relationship with this counselor and they’re going to be able to help me through every problem I’ve got, whenever I want, wherever I want it?’.”

Campbell says psychologists are meant to set goals with clients and when those goals are reached suggest a break from therapy.

BetterHelp’s push into Australia is a two-sided coin, Campbell says. On the one hand, “we have a huge demand for mental health services that needs to be met and the space is there for mental health offerings.”

“The other side of the coin is about the quality and the safety of the service … and that’s my concern about BetterHelp. Because it has a reputation of doing, I would say, quantity over quality.”

Carlton says if people feel let down by the platform there is a risk they won’t seek mental health care in the future.

A spokesperson for BetterHelp said “we are confident in the quality and safety of our offerings.”

The spokesperson said therapists were offered competitive compensation of up to A$137,410 (US$91,700) a year based on 52 working weeks — but actual earnings varied due to conversion rates, caseload and client engagement on the platform.

“Our compensation model is designed to be competitive, and we regularly review it to ensure it meets the needs of our therapists. We also provide extensive support and supervision to maintain high standards of care and therapist satisfaction,” the spokesperson said.

After canceling her BetterHelp subscription, Elizabeth decided to see a private practice therapist via telehealth for one hour every three weeks. She thinks that’s better value and gives her time to reflect and work towards her goals.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she