We meet in a branch of McDonald’s on Dasyue Rd (大學路) just opposite the leafy campus of Tainan’s National Cheng Kung University, where Bruce Humes occasionally likes to “sneak into the Engineering Department’s shaded, Japanese-style courtyard for a snack.”

It’s not yet 7am but Humes has already been up for two hours scanning the news before he begins translating a new novel, Hollowed Out, by Liu Liangcheng (劉亮程).

“This is the only place open early enough for me,” he says over coffee.

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

The American polyglot is enjoying a comfortable life in Tainan translating contemporary fiction and non-fiction.

“I lived in Taipei in 1978,” he says, “and I could never get anything dry during the plum rains. The weather is much more pleasant here, plus living costs are lower. From my perspective, having spent years in China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen, Tainan is a village. You can cycle and walk everywhere.”

KEEPING BOOKISH

Photo courtesy: Bruce Humes

Notwithstanding the warm climes and laidback atmosphere in the neighborhood where Humes lives, he’s nothing if not busy and can often be found at the National Museum of Taiwan Literature (國立臺灣文學館) writing and translating. He’s best known for renditions of two novels, Wei Hui’s (衛慧) Shanghai Baby (1999) and The Last Quarter of the Moon (2005) by Chi Zijian (遲子建). But his latest two works, both published this year, are decidedly more academic.

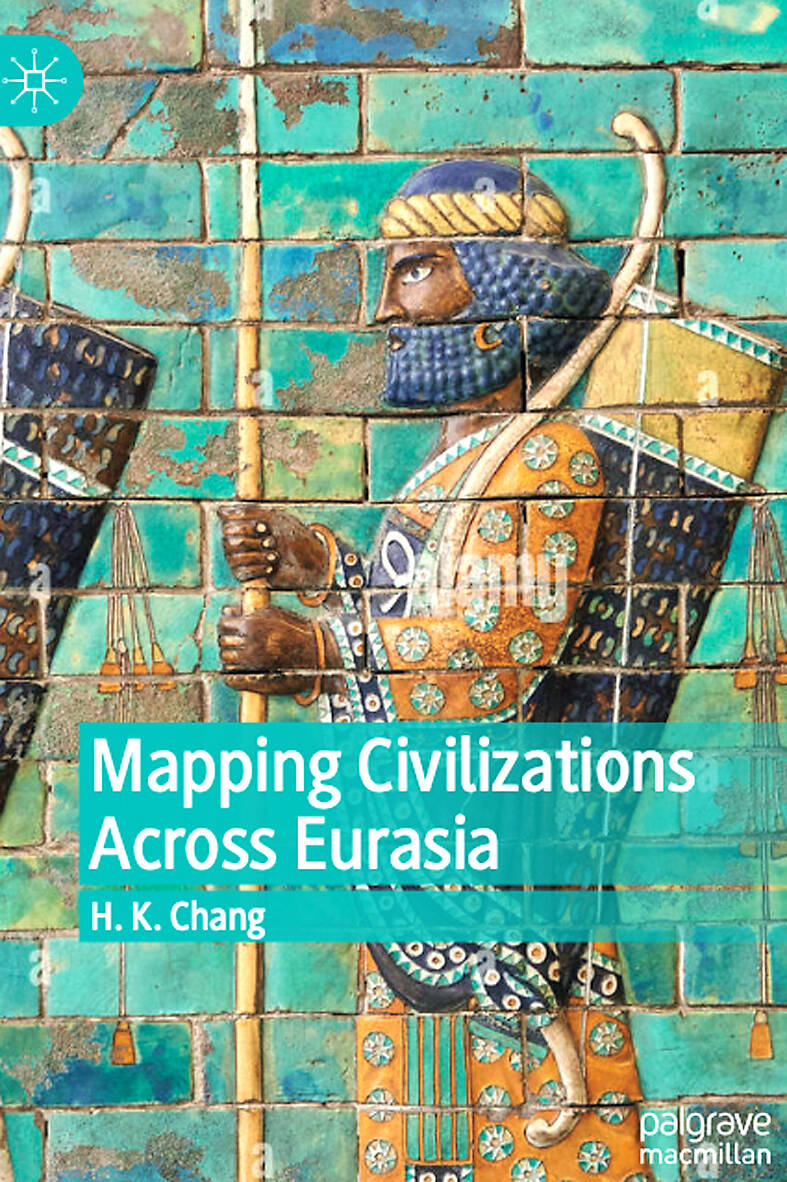

The first is Mapping Civilizations Across Eurasia by H.K. Chang (張信剛), a half-Manchu, half-Han scholar who was born in China’s Shenyang, raised in Taiwan and earned a PhD in biomedical engineering in the US.

Humes says Chang spent much time roaming the Silk Road and has been to most of the main sites from Xian over to Turkey and down to India. He adds that he’s worked on five of Chang’s books, most of which are about Eurasia, but they often emphasize the impact of westward-bound East Asian conquerors, such as the Mongols and Turkic peoples, on Central and West Asia.

Photo courtesy: Bruce Humes

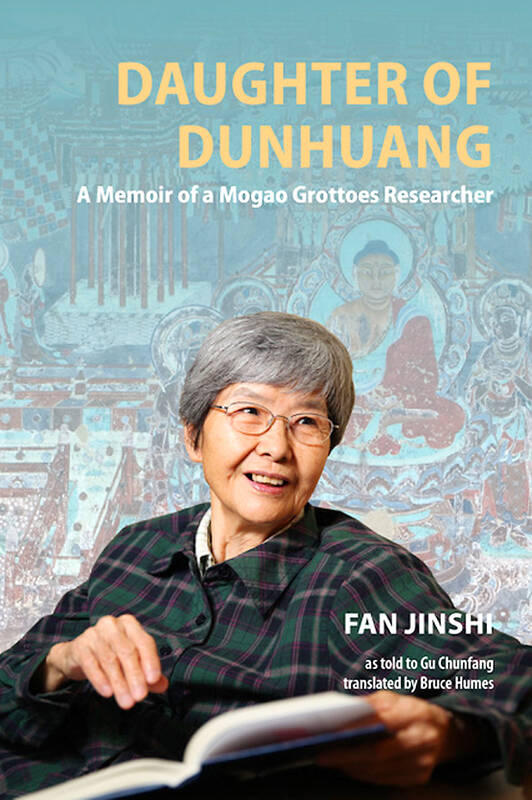

The other recently-published title Humes translated is Daughter of Dunhuang: A Memoir of a Mogao Grottoes Researcher by Fan Jinshi (樊錦詩).

“She’s just an incredible lady,” Humes says. “An archaeology graduate who spent 50-plus years in the desert overseeing the restoration and preservation of Buddhist cave-temples in Gansu Province. Raised in comfortable Shanghai, she endures all kinds of hardships while trying to save those Silk Road murals.”

The original sold half a million copies in Chinese, and will eventually appear in Hindi, Russian, Farsi and Turkish.

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

LIFE’S JOURNEY

Outside of the two decades he spent working in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Humes, a keen traveler, has been fortunate enough to call a number of exotic locales home, including Penang and Istanbul. But his most enduring overseas relationship has been with Taiwan.

“After returning to the University of Pennsylvania from a year-aboard in Sorbonne in Paris, I felt I’d got French under my belt, so I dropped it in favor of Chinese.”

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

Upon graduation, Humes waited on tables for several months, jealously guarding his tips in order to begin his East Asian adventure.

“When I had enough money, I bought a one-way ticket to Taipei.”

Humes lodged in free homestays and audited classes at National Taiwan Normal University to hone his language skills, living in what is today’s Banciao District (板橋) in New Taipei City.

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

“It was just an incredibly chaotic place. Within three months I must have seen four or five motorcyclists dead on the road,” he says.

Humes describes a very different cityscape from the malls and skyscrapers of contemporary Taipei: “First-floor garage-like shops dominated, with the owners working in front and sleeping in the back.”

Despite describing the Taiwanese capital as “filled with a unique fragrance melding motorcycle fumes and open-air sewage,” Humes recalls his time in Taipei fondly.

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

‘WELCOME TO CHINA’

The political climate of the day also contrasted starkly with our time.

“‘Welcome to China!’ was the standard greeting. Censorship was omnipresent and lots of topics were taboo. I remember saying something mildly derogatory about Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and being told off,” he says.

When it was announced that the US would formally recognize the communist PRC, it was known as the “great betrayal.”

One of the few foreigners in the Chinese department at National Taiwan Normal University, a committee brought a big character poster to his house, denouncing then-US president Jimmy Carter for breaking ties with the Republic of China while establishing relations with the “Communist bandits.”

“They pressed me to put my name to it,” he says.

After a year in Taiwan, Humes moved to Hong Kong to be with his sweetheart and flesh out his career, but would continue to visit regularly. In 1988, Humes returned again, this time grieving the loss of his mother Joy Humes, a multi-lingual professor of French literature from whom he’d inherited his passion for languages.

“I came for about four months as part of my recuperation process to study ancient poetry at Taipei Language Institute. My teacher would help me do a deep dive into a single poem each day,” he says of how the melancholy lyrics penned by Tang-era scribes helped him through this sad period.

It wasn’t, however, until 2015 that Humes would return to Taiwan to live. He’d been living in China for years and set up a blog, which attracted attention.

“My activities apparently attracted official attention and I was ‘invited to take tea,’” he says, using the popular euphemism for an informal interrogation. “Unfortunately, under Xi Jinping (習近平), the space for creative writing was closing and there was a lot less you were permitted to write about, especially if you were not Han.”

Internet censorship expedited Humes’ departure, a pioneer in what he dubs “the great China fallout” that saw many old China hands scramble for the exit gate even before the pandemic.

Although he regularly travels elsewhere in Asia, and beyond, he describes Tainan “as close as anything I’ve had to somewhere that feels like home,” adding, “Of course I wanted to continue living in the Sinophone world. But I think it’s largely because I’ve found people here so tolerant and kind.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she