In Tainan’s Annan District (安南), a pond-pocked wedge of land juts out into the Yanshui Estuary (鹽水溪口). Salt scents the breeze and the soft slapping of water against mangroves is broken only by the occasional dinosaur squawk of an egret in flight.

Gazing seawards from the tip of this wedge, Sicao Bridge (四草大橋) separates the observer from the Taiwan Strait, while at the levee’s leeward base, an unassuming sign states, “Mountains to Sea Greenway — 0km.”

Casual visitors would likely cycle past without stopping, but for some, this spot marks the beginning of a multi-day adventure from the coast to the summit of the country’s highest peak — Jade Mountain (玉山).

Photo: Ami Barnes

Covering 188km, the Mountains to Sea National Greenway (山海圳國際綠道), is a hiking and biking route linking two National Parks, three National Scenic Areas and several distinct forest biomes.

Along its footpaths and roads, visitors can find traces of Dutch colonial history, temples established by early Han Chinese settlers, ambitious Japanese-built infrastructure projects and indigenous villages.

In short, it offers a slow-travel window into the diverse natural and cultural forces that have shaped contemporary Taiwan.

Photo: Ami Barnes

The route consists of four sections that can be completed either independently or as a through-hike. This piece is the first in a series of four and focuses on the first segment — the Inner Sea Trail (內海之路)

THE INNER SEA TRAIL

At 30.8km and with little elevation gain, the Inner Sea Trail can be completed in a day using YouBikes.

Photo: Ami Barnes

The scenery along the first stretch is distinctly littoral — think oyster beds bobbing gently in the tidal waters and waders stalking the muddy foreshore.

Indeed, Taijiang National Park’s wetlands are renowned for birdlife, with winters drawing flocks of avian aficionados hoping to sight the endangered black-faced spoonbill.

Four hundred years ago, around the time when the Dutch East India Company established a base in Taiwan, much of this area was submerged beneath an expansive lagoon called Taijiang Inner Sea (台江內海).

Photo: Ami Barnes

Transposed onto modern-day Tainan, this feature — from which the Inner Sea Trail draws its name — stretched south to Jhongsi District (中西), east to Anding (安定) District, and north beyond Jiangjun District (將軍).

Centuries of river-borne sediment and flooding events have nudged the coastline westward — a process compounded by the endeavors of farmers claiming parcels of land from the waters to raise Tainan’s prized milkfish.

As the fish ponds segue into food stalls and stores, turn left and take a detour towards Chaohuang Temple (朝皇宮).

Established in 1878, recent decades have seen Chaohuang Temple spearheading a movement to return temples to their role at the center of community life — proof of which abounds in the many photos displayed on its walls.

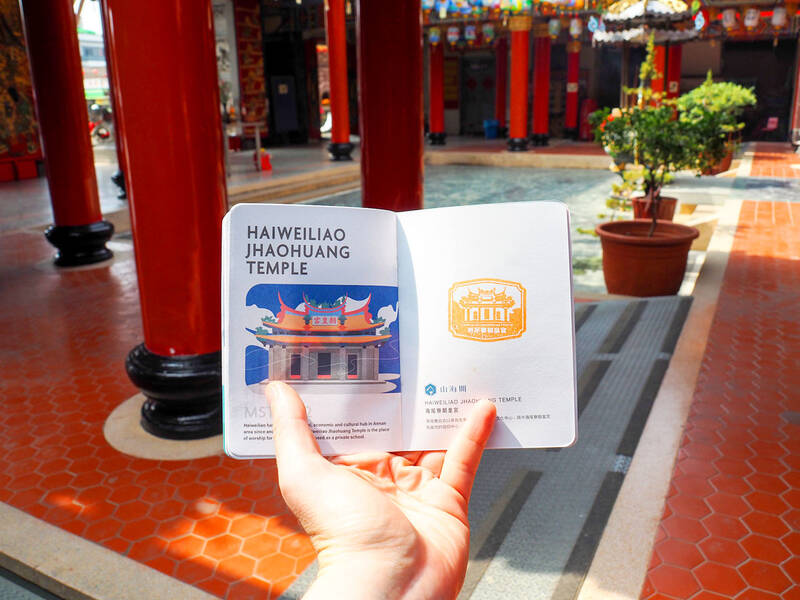

Travelers can pause here to fill their water bottles, pray for safe travels and collect one of the eight route’s trail passport stamps.

A GENERAL’S TEMPLE

Another brief detour leads to General Flying Tiger’s Temple (飛虎將軍廟).

Enshrined within is Sugiura Shigemine, an Imperial Japanese Navy pilot credited with saving many people at the cost of his own life when his plane sustained serious damage during a World War II dogfight.

Although Sugiura’s sacrifice was largely forgotten in the aftermath of the war, villagers reported sightings of a wandering spirit clad in a Japanese navy uniform.

Chaohuang Temple’s main deity was consulted and advised venerating the spirit with a shrine. This was evidently efficacious because sightings of the ghostly aviator have since ceased.

Back on the trail, the next point of interest is the National Museum of Taiwan History (國立臺灣歷史博物館), where a handily placed YouBike dock makes it easy to pause and enjoy the museum’s excellent bilingual displays.

From the museum, the route cuts through Southern Taiwan Science Park’s (南部科學園區) fabrication plants and banks of solar panels before passing first under the high-speed rail line and then over the TRA tracks.

Keep straight until reaching the fast-flowing waters of Chianan Irrigation Canal’s Southern Main Line (嘉南大圳南幹線). Here, the Inner Sea Trail turns left to follow the canal for a short way before terminating at Jiaba Tianhou Temple (茄拔天后宮).

A statue of the sea goddess Matsu (媽祖) presides over the temple’s main altar and has done so since 1661, when she accompanied a boatload of Fujian immigrants on their voyage to a new life.

Out in the courtyard, villagers sit in the shade of a sprawling twin-trunked banyan, beside a historic well that’s at least as old as the temple itself.

While no longer a communal water source, the well plays a central role in annual Dragon Boat Festival celebrations as hundreds participate in the custom of drawing lucky noontime water (打午時水).

At the end of the Inner Sea Trail, day trippers can ride back into Shanhua (善化) to catch the train, while those embarking on a longer journey have the option of spending the night in Shanhua or continuing on to Liujia (六甲).

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the