It’s one of those strange but immutable truths of the movies that a song like Earth, Wind & Fire’s September can play in roughly a thousand films before a movie about a dog and a robot comes along and blows them all out of the water.

The animated Robot Dreams is wordless, so the songs play an outsized influence in conjuring its whimsical and gently existential tone. But Pablo Berger’s Robot Dreams, a 1980s New York-set fable about loved ones who come and go, doesn’t just use September for a scene or even two. It’s the soundtrack to the friendship between Dog and Robot (yes, those are the protagonists’ names in this disarmingly simple film), and its melody returns in various forms whenever they’re reminded of each other.

To a remarkable degree, Robot Dreams has fully imbibed all the melancholy and joy of Earth, Wind & Fire’s disco classic. Just as the song asks “Do you remember?” so too does Robot Dreams, a sweetly wistful little movie that, like a good pop song, expresses something profound without wasting a word.

Photo: AP

Remembering is also helpful when it comes to the film, itself. I first saw Robot Dreams over a year ago at the Cannes Film Festival. Its release comes months after Robot Dreams was Oscar nominated for best animated film. But for whatever reason, the film is only arriving in North American theaters this Friday.

It’s an unconventional release pattern for an unconventional film. Robot Dreams, adapted from Sara Varon’s 2007 graphic novel, is likewise an all-ages movie in a curious way. It’s very much for kids, but it’s also so mature in its depictions of relationships that older generations may swoon hardest for it.

Robot Dreams begins in the East Village where Dog lives a rather lonely life. Before he sits down to eat a microwave dinner, he notices his solitary reflection in the TV screen. An ad, though, sparks Dog to order the Amica 2000. A few days later, a box arrives, Dog assembles its contents and soon a friendly robot is smiling back at him.

Photo: AP

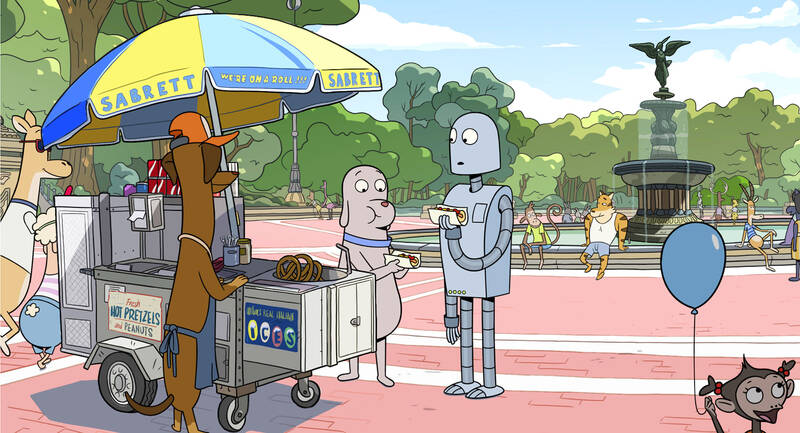

Together, they have a grand old time around a New York colorfully rendered with pointillist detail. They jump the subway turnstiles, visit Woolworths and rollerblade in Central Park (with September playing on the boombox). But after an outing to Playland (which looks much more like Coney Island), Robot’s enthusiasm gets him into some trouble. After frolicking in the water, he lies down on the beach and later finds he can’t move. This may be a movie about a Dog who rollerblades and a Robot who eats hot dogs, but the scientific reality of rust is one suspense of disbelief too far for Robot Dreams.

Despite all of Dog’s efforts, Robot is stuck, and, this being September, the beach is soon closed for the off-season. Much of Robot Dreams passes through the seasons while Robot dreamily sleeps through the winter and Dog is forced to go on with his life, and maybe try to meet someone new.

The dreams of each can be surreal; Dog has a bowling alley visit with a snowman who bowls his own head, while Robot imagines a Wizard of Oz-like fantasy. But both are consumed by fears of their friend’s abandonment while progressively finding new experiences and friends. New characters enter, with their own New Yorks (kite-flying in the park, rooftop barbecues) and their own soundtracks. Robot Dreams movingly turns into a story about moving on while still cherishing the good times you once shared with someone — a valuable lesson to young and old, in friendship and romance.

And even this sense of memory runs deeper in Robot Dreams than you might be prepared for. Berger, the Spanish filmmaker whose movies include the 2012 black-and-white silent Blancanieves, has filled his movie with countless bits of a bygone past, from Atari to Tab soda. The name Amica 2000 could be a pun for the Amiga 500, the early computer and harbinger of our digital present. Even more dramatic, though, is the way the Twin Towers often loom in the background in a film so connected to the month of September. There, too, is a poignant symbol of companions, friends and family members who vanished, but whose memories still stir within us.

This is, you might be thinking, a lot for a cartoon about a dog and a robot to evoke. And yet Robot Dreams does so, beautifully. And it will leave you curiously lifted by the spirit and lyrics of one of the most-played wedding songs of all time: “Only blue talk and love, remember/ The true love we share today.”

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

This was not supposed to be an election year. The local media is billing it as the “2025 great recall era” (2025大罷免時代) or the “2025 great recall wave” (2025大罷免潮), with many now just shortening it to “great recall.” As of this writing the number of campaigns that have submitted the requisite one percent of eligible voters signatures in legislative districts is 51 — 35 targeting Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus lawmakers and 16 targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers. The pan-green side has more as they started earlier. Many recall campaigns are billing themselves as “Winter Bluebirds” after the “Bluebird Action”

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American