In the hills outside the Tajik capital Dushanbe, shepherd Bakhtior Sharipov was watching over his flock of giant Hissar sheep.

The breed, prized for profitability and an ability to adapt to climate change, garners celebrity status in the Central Asian country, which is beset by a shortage of both meat and suitable grazing land.

“They rapidly gain weight even when there is little water and pasture available,” 18-year-old Sharipov said.

Photo: AFP

Facing a serious degradation in farmland due to years of overgrazing and global warming, the hardy sheep offer a potential boon to Tajikistan’s farmers and plentiful supply of mutton to consumers.

Around 250 of the animals — instantly recognizable by two fatty lumps on their rear end — were grazing in the early spring sun under Sharipov’s watch. “These weigh an average of 135 kilograms (300 pounds). It’s the end of winter, so they’re not as heavy, but they’ll put on weight quickly,” he said.

A white Central Asian shepherd dog, almost as large as the sheep he was watching over, stood on guard.

Photo: AFP

The largest Hissar rams can weigh over 210 kilograms (460 pounds).

Able to yield meat and fat of around two-thirds their total weight — more than most other breeds, many of which also consume more — they can be highly profitable for farmers.

‘IMPROVE THE LAND’

Photo: AFP

“The Hissars are a unique breed, first because of their weight,” said Sharofzhon Rakhimov, a member of the Tajik Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

“Plus these sheep never stay in the same spot so they contribute to improving the land’s ecosystem,” he said. They can wander up to 500 kilometers (300 miles) in search of grazing land between seasons, helping pastures in different regions regenerate. The decline in land quality is one of the main environmental challenges facing Central Asia. Around 20 percent of the region’s land is already degraded, affecting 18 million people, according to a UN report.

That is an area of 800,000 square kilometers (nearly 310,000 square miles), equivalent to the size of Turkey.

The dust churned up by the arid ground can fuel cardio-respiratory diseases.

Facing a hit to their livelihoods as their land becomes ever less productive, many farmers choose to emigrate.

In such an environment, the status of Hissar sheep — able to thrive in the tough conditions — is of serious public interest for Tajikistan.

Among the dozens of posters glorifying Tajik President Emomali Rahmon that line the road into the Hissar valley, stands a golden-colored monument to the three kinds of Hissar sheep.

EXPENSIVE SHEEP

At his biotech center near the capital, scientist and breeder Ibrokhim Bobokalonov harnesses genetic samples of the very best specimens in the hope of rearing the largest and most profitable sheep. “Demand for Hissar sheep is growing not only in Tajikistan, but also in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Turkey, Azerbaijan, China and even the US,” Bobokalonov said.

The animals have even become a source of rivalry in the region.

Tajikistan recently accused its neighbors of tampering with the breed, crossing it with other local varieties to create even heavier sheep.

A Hissar weighing 230 kilos was recorded at an agricultural competition in Kazakhstan last year, setting a Guinness World Record. Others in Kyrgyzstan have surpassed 210 kilos. Tajik breeders say they are intent on staying ahead. “Here’s Misha. He weighs 152 kilograms and is worth $15,000,” Bobokalonov said, standing in front of a sheep lying on the scales with its legs tied together.

The sum is equivalent to six years’ average salary in Tajikistan. Bobokalonov plans to sell him later this year.

“I hope that by the time of the competition this summer, he will weigh 220-230 kilograms. Just by feeding him natural products, without doping, he can put on around 800 grams a day,” Bobokalonov said.

In Kazakhstan, a sheep sold for US$40,000 in 2021.

While farmers like the Hissars for their profitability, the sheep is famed among the wider population for its flavor.

Mutton is an essential ingredient in central Asian fare.

Scouring the offering at a local market, shopper Umedjon Yuldachev agreed.

“You can cook any Tajik national dish with this mutton.”

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

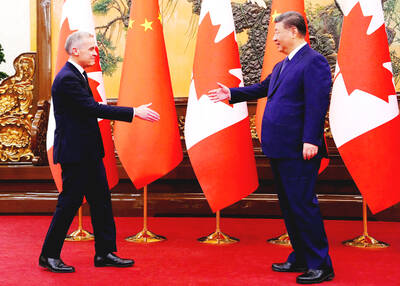

Britain’s Keir Starmer is the latest Western leader to thaw trade ties with China in a shift analysts say is driven by US tariff pressure and unease over US President Donald Trump’s volatile policy playbook. The prime minister’s Beijing visit this week to promote “pragmatic” co-operation comes on the heels of advances from the leaders of Canada, Ireland, France and Finland. Most were making the trip for the first time in years to refresh their partnership with the world’s second-largest economy. “There is a veritable race among European heads of government to meet with (Chinese leader) Xi Jinping (習近平),” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director