The “one country, two systems” principle has been Beijing’s paramount approach to Taiwan since 1982. Taiwanese and Chinese are described by Beijing as compatriots who come from the same “family” and shoulder the same responsibility to revive the “glory of the Chinese nation.” The words “home” and “family” have been continually employed to underscore the kinship, emotional ties and shared cultures of Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Non-government sponsored film and literature, however, tell another story, showing Chinese artists’ divergent views about Taiwan.

FOUR DECADES OF SEPARATION

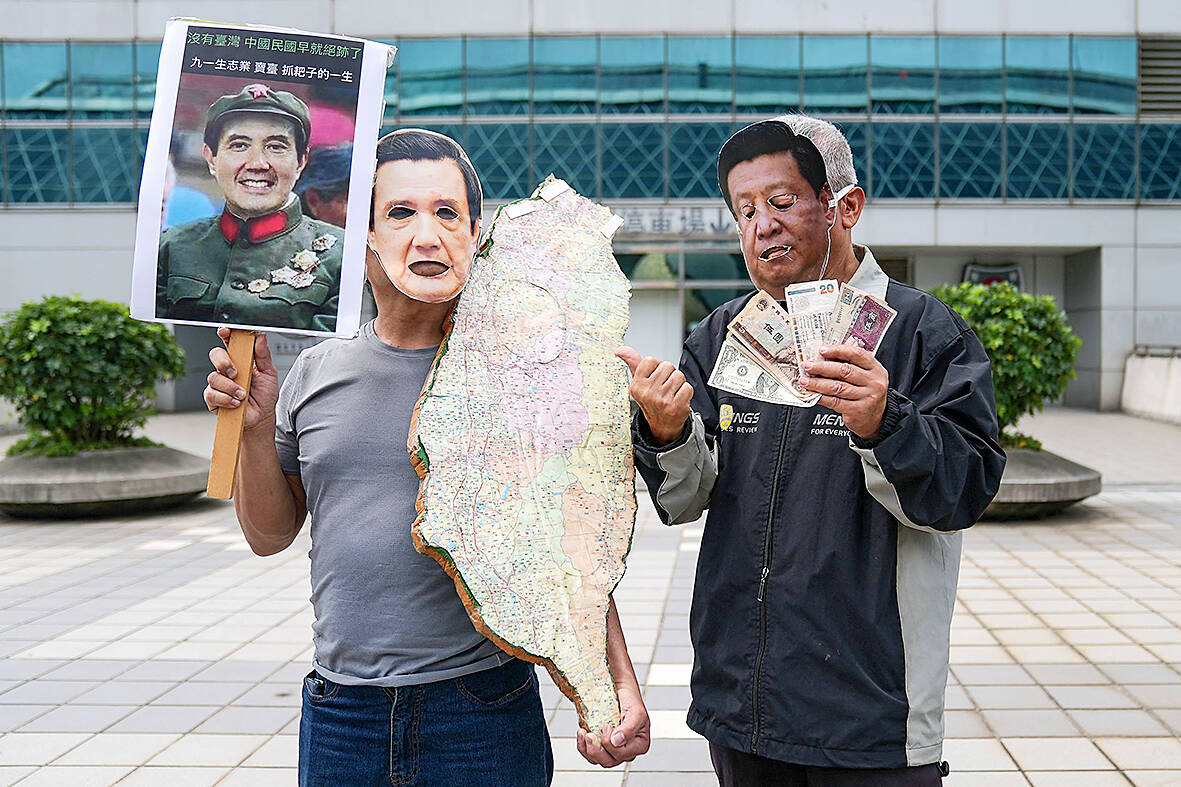

Photo: AFP

Wang Quanan’s (王全安) Shanghainese language film Apart Together (團圓) is one of the very few works on this theme that successfully passed Chinese censorship and was released in China. It recounts a story of a Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) soldier Liu Yansheng’s reunion with his wife Yu-e, whom he left behind in 1949 while he followed the KMT to Taiwan. After Liu’s Taiwanese wife dies, Liu returns to China to visit Yu-e planning to take her to Taiwan. But Yu-e has married a gentle and easy-going People’s Liberation Army (PLA) soldier Lu Shanmin and has a new family. Lu sacrificed his military career for her, and he also raises Liu and Yu-e’s son. Liu Yanshen’s return almost tears Lu and Yu-e’s family apart, as Lu is so kind that he promises to divorce Yu-e and let her go. At the end of the film, Yu-e decides to stay with Lu. Because of Liu’s visit, she realizes the meaning of love and she sees it from Lu.

Throughout the film, Liu is presented as an outsider and even “invader” unwelcomed by this Chinese family. By drawing a highly allegorical contrast between the loyal and responsible Lu and the passionate, yet selfish Liu, the director presents his view of the cross-strait relationship, showing that Taiwan is not so much a member of the Chinese family as an awkward outsider. While largely sympathetic to the Beijing’s perspective, the film questions the possibility of a happy reunion after four decades of separation.

Compared with the very limited number of movies on the topic of Taiwan, young Chinese, particularly the post-1980s generation, have been keen to write about Taiwan after Taiwan’s ban on Chinese visitors was lifted in 2008. Many of these literary works were first disseminated online and then, because of their popularity, published in book form. Most of the works are prose essays (散文) focused on the authors’ lived or travel experience in Taiwan and particularly discuss the cultural differences between the two sides of the Strait.

Photo: AP

The well-known Chinese blogger/writer Han Han’s (韓寒) The Winds of the Pacific Ocean (太平洋的風) is an account from an independent traveler. It is a brief prose essay first posted on Han’s Weibo blog in 2012 (and it was subsequently blocked in the 2020s). It was read 400,000 times and shared 170,000 times on the first day it was released. The essay provoked wide discussion among young Chinese regarding the cultural differences between Taiwan and China. Han praises Taiwan for its civilization and goes so far as to thank Taiwan and Hong Kong for protecting the traditional Chinese culture (中華文化) from being damaged by cultural and political catastrophes in China. Beijing’s “one country” discourse is undermined in Han’s work, and Taiwanese culture is interpreted as a “better system” than that of the PRC.

In 2011, the first group of around 1,000 PRC students arrived in Taiwan. In 2012 and 2013, as many as 10 books written by them were published, most of which revolve around the impacts the study/lived experience had in terms of cultural identification. These writers call Taiwan “an alien land” to demonstrate their displacement on the island. Cai Boyi (蔡博藝), whose work I am in Taiwan, I am Young (我在台灣,我正青春) was published both in Taiwan and China, wrote about her experience of being seen as “the other” by Taiwanese: “I am already used to be called a Chinese (中國人) by my Taiwanese classmates. I no longer argue with them. I am upset, but I no longer have the motivation and position to ask them cynically, ‘Aren’t you Chinese?’ They indeed don’t think they are. Now at most I reply, ‘Please call me Mainlander (大陸人).’”

CULTURE SHOCK

Zhang Yiwei (張怡微) is the only PRC writer who has continuously published Taiwan-focused literary works in China over several years. Zhang moved to Taiwan in 2010 as an exchange student and from 2011 she studied for a PhD degree. Before she left Taiwan in 2017, she had published three literary works about Taiwan. Her work is to date the most important and detailed literature that presents a PRC student’s psychological transformation in Taiwan. Zhang’s work describes her cultural shock after she moved to Taiwan, her isolation and displacement, and the adjustment of her own position as an alien on the island so as to re-understand Taiwan. In the epilogue of For Dreaming of Your Leaving (因為夢見你離開), Zhang says that her feelings about Taiwan are like the process of knowing a person: “I have gradually grown to recognize his [Taiwan’s] kindness, hardships, and sorrow. And he also has learned my prejudices and stubborn-ness. Our relationship seems so close, and yet accidental.”

Zhang’s narrative shows how a Chinese writer comes to adopt a more thorough understanding of Taiwan as well as the cross-strait issue which, she hints, lacks a straightforward approach to resolution.

While the views of these cultural works may be contradictory or even conflicting, they demonstrate that ordinary Chinese people’s feeling about Taiwan are not as homogeneous as often assumed but are instead dynamic and diverse.

Phyllis Yu-ting Huang (黃鈺婷) received her PhD in Chinese Studies from Monash University. Huang is Secretary General of the Australasian Taiwan Studies Association. She is also a research affiliate at Monash University. She is the author of Literary Representations of ‘Mainlanders’ in Taiwan: Becoming Sinophone (Routledge, 2021). A longer version of this article was originally published by Melbourne Asia Review, Asia Institute, University of Melbourne.

Feb. 17 to Feb. 23 “Japanese city is bombed,” screamed the banner in bold capital letters spanning the front page of the US daily New Castle News on Feb. 24, 1938. This was big news across the globe, as Japan had not been bombarded since Western forces attacked Shimonoseki in 1864. “Numerous Japanese citizens were killed and injured today when eight Chinese planes bombed Taihoku, capital of Formosa, and other nearby cities in the first Chinese air raid anywhere in the Japanese empire,” the subhead clarified. The target was the Matsuyama Airfield (today’s Songshan Airport in Taipei), which

On Jan. 17, Beijing announced that it would allow residents of Shanghai and Fujian Province to visit Taiwan. The two sides are still working out the details. President William Lai (賴清德) has been promoting cross-strait tourism, perhaps to soften the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) attitudes, perhaps as a sop to international and local opinion leaders. Likely the latter, since many observers understand that the twin drivers of cross-strait tourism — the belief that Chinese tourists will bring money into Taiwan, and the belief that tourism will create better relations — are both false. CHINESE TOURISM PIPE DREAM Back in July

Could Taiwan’s democracy be at risk? There is a lot of apocalyptic commentary right now suggesting that this is the case, but it is always a conspiracy by the other guys — our side is firmly on the side of protecting democracy and always has been, unlike them! The situation is nowhere near that bleak — yet. The concern is that the power struggle between the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and their now effectively pan-blue allies the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) intensifies to the point where democratic functions start to break down. Both

This was not supposed to be an election year. The local media is billing it as the “2025 great recall era” (2025大罷免時代) or the “2025 great recall wave” (2025大罷免潮), with many now just shortening it to “great recall.” As of this writing the number of campaigns that have submitted the requisite one percent of eligible voters signatures in legislative districts is 51 — 35 targeting Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus lawmakers and 16 targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers. The pan-green side has more as they started earlier. Many recall campaigns are billing themselves as “Winter Bluebirds” after the “Bluebird Action”