Taiwan’s human population is trending downward, yet the greens and browns of its farmlands and forests are increasingly broken up by the black of asphalt and the gray of concrete.

According to a reconstruction of changes in land cover between 1904 and 2015 by the Academia Sinica’s Center for Geographic Information Systems, published in Scientific Reports in 2019, at the end of the 1895-1945 period of Japanese colonial rule, no more than 530km2 of Taiwan (less than 2 percent of its total land area) was built up.

Rapid population growth and industrialization caused the land area devoted to housing and infrastructure to balloon from about 800km2 in 1969 to 4,400km2 in 1995. In the two decades that followed, the built-up area reached 4,800km2.

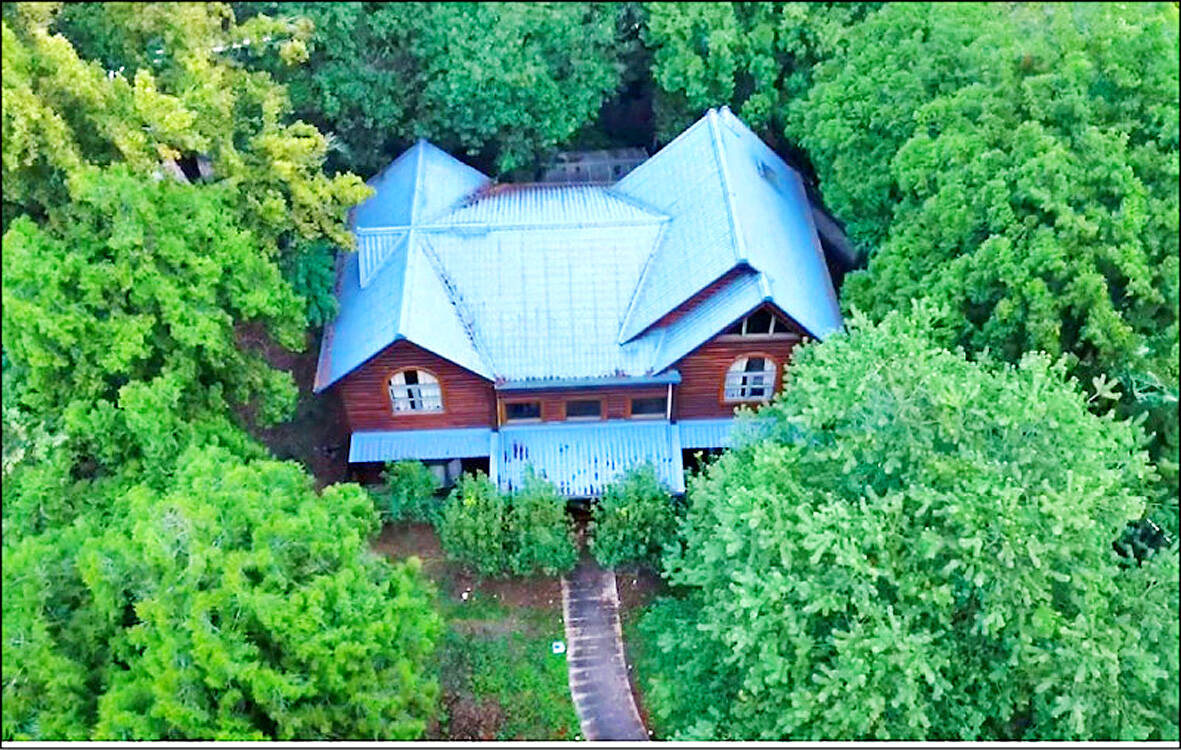

Photo: Steven Crook

Over the course of the 20th century, three quarters of Taiwan’s grassland disappeared. Much of it was turned into farmers’ fields, as were patches of low-altitude woodland.

The Academia Sinica study pointed out that the amount of land devoted to farming has been declining since the late 1950s. In recent years, some has been assigned to government-led afforestation projects — but far more has been lost to a combination of urban sprawl, government-backed industrial zones, so-called “farmhouses” (see Taipei Times, “Protecting Taiwan’s green spaces one ping at a time,” 10) and illegal development.

In last year’s March issue of Land Use Policy, two local scholars noted that Taiwan’s agricultural land shrank from 900,062 hectares in 1981 to 793,026 hectares in 2017, and argued that “strict law enforcement and consistent policy are required to correct” the price, tax and other distortions that drive farmland loss. Even now, rather than redevelop brownfield sites — of which Taiwan has plenty — many new industrial and residential buildings are constructed on greenfield sites.

Photo: Steven Crook

Food security isn’t the only reason why Taiwan should try harder to save its remaining green spaces from being paved over. Farms don’t preserve biodiversity or sequester carbon as well as woodlands or natural grasslands, but in both regards they’re preferable to roads and buildings. Patches of land that aren’t covered with asphalt or concrete are able to soak up rainfall, recharging groundwater and reducing the risk of flooding. What’s more, they don’t exacerbate the urban heat island effect.

ILLEGAL FACTORIES

Farmland is so often illegally converted to other uses that no one seemed especially surprised when, just before the January presidential election, it emerged that a plot zoned for agriculture and co-owned by Taiwan People’s Party candidate Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) had been turned into a parking lot for buses. Ko said he’d sell the plot and donate any profits generated from illegally renting it out for social welfare and disaster relief.

Photo: Steven Crook

Because they may contaminate nearby fields, the thousands of factories which operate illegally on or adjacent to agricultural land are a particular cause for concern.

The Factory Management Act (工廠管理輔導法) was amended in 2019 to require Taiwan’s local governments to “suspend the electricity and water supply and demolish the unregistered factories” that appeared after May 20, 2016. In mid-2020, environmental advocacy organization Citizen of the Earth, Taiwan suggested that more than 20,000 business sites might fall into this category.

What happens to those that can prove they began operations before that deadline depends on whether they’re categorized as “low pollution” or not. Those that aren’t must relocate to a site where they can become properly licensed and registered, or face being closed down.

Photo: Liao Hsueh-ju, Taipei Times

Low-pollution unregistered factories have a chance of staying in business if they apply for “management and guidance” under Chapter 4-1 of the Act and pay an annual fee of between NT$20,000 and NT$100,000, depending on the factory’s size. So long as air pollution, wastewater, and other standards are observed and rezoning the land is possible, this puts them on a pathway to becoming properly licensed. Businesses that don’t fall within the scope of the Act, such as warehouses and vehicle repair shops, aren’t eligible.

On Feb. 26 this year, the Ministry of Economic Affairs’ Industrial Development Administration (IDA) published a list of 32,802 low-pollution illegal factories that have applied to join this scheme. Some 4,098 are in New Taipei; another 3,137 are in Taoyuan. According to IDA’s Web site, by December last year, 8,443 applicants had graduated from the program to become fully licensed manufacturing sites.

The IDA has also released a list of 3,637 low-pollution unregistered factories that haven’t applied under Chapter 4-1. New Taipei has 706 such factories, while 635 are in Kaohsiung. There are 622 in Taoyuan, 349 in Miaoli County and 336 in Changhua County.

Photo: Ko Yo-hao, Taipei Times

Rather than name and shame these businesses, the IDA has partly redacted the name of each one, and the addresses shown are incomplete. What message does this — and the entire program — send to entrepreneurs who aren’t sure whether to follow the rules? And some might say that allowing any illegal factory to become fully licensed is unfair on enterprises that have obeyed the law from the get-go.

Politicians are aware that a ruthless crackdown on illegal enterprises would destroy jobs often done by older, rural and less educated voters. It might even disrupt supply chains. In any case, local government staff shortages make decisive action highly unlikely. A 2022 investigation by Citizen of the Earth, Taiwan indicates that Changhua County might need 105 years to clear its backlog of uninvestigated factories, while Tainan could require 99 years.

CLEAN POWER VS AGRICULTURE?

Photo provided by reader

Taiwan’s push for renewable energy has resulted in large-scale photovoltaic arrays taking over tracts of countryside, especially in the south. It’s unclear just how much farmland will have to be sacrificed for the country to achieve its net-zero ambitions — but well before then the proliferation of solar farms might undermine parts of the agricultural sector.

If most of the land in a particular township is converted to photovoltaics, certain farming-related businesses might cease to be viable. And if the area’s remaining farmers have to travel further to purchase agrochemicals or have their machinery repaired, they’re less likely to turn a profit and more likely to quit. Taiwan will get the clean energy it needs — but at the price of a domino effect that could drag down the country’s already-low food self-sufficiency rate.

Much of the unnecessary development and illegal land conversion that blights Taiwan’s countryside is the result of a lack of integrated planning to anticipate and balance the demand for land for various purposes, says Tsai Jia-shen (蔡佳昇), formerly a researcher at Citizen of the Earth, Taiwan.

“The Spatial Planning Act (國土計畫法) [passed by the Legislative Yuan in late 2015] is seen as the solution by many, as it establishes a systematic land use regulation framework. But enforcement remains a significant challenge. Despite fines or even criminal penalties for illegal land conversion, the inertia in local governance hinders the progress expected by planners and environmentalists,” Tsai says.

He thinks the reasons for this may include “a lack of education, instances of corruption, the influence of capitalist interests, Taiwan’s development status and its position in the global supply chain.”

Tsai, who’s currently studying for a master’s degree in environmental management at Duke University in the US, stresses that there are no quick fixes for Taiwan’s land-use problems.

“In my opinion, a bottom-up management approach is preferable to top-down regulation. Whether discussing regional or national-scale industrial or agricultural development — even though the latter is undervalued monetarily — I believe in the power of community solidarity. The critical step is to build or rebuild communities in rural areas that can effectively communicate and discuss public interests rationally. Only through strong local solidarity can they resist the allure of short-term economic gains at the expense of their environment, health and security,” he says.

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

Climate change, political headwinds and diverging market dynamics around the world have pushed coffee prices to fresh records, jacking up the cost of your everyday brew or a barista’s signature macchiato. While the current hot streak may calm down in the coming months, experts and industry insiders expect volatility will remain the watchword, giving little visibility for producers — two-thirds of whom farm parcels of less than one hectare. METEORIC RISE The price of arabica beans listed in New York surged by 90 percent last year, smashing on Dec. 10 a record dating from 1977 — US$3.48 per pound. Robusta prices have

A few years ago, getting a visa to visit China was a “ball ache,” says Kate Murray. The Australian was going for a four-day trade show, but the visa required a formal invitation from the organizers and what felt like “a thousand forms.” “They wanted so many details about your life and personal life,” she tells the Guardian. “The paperwork was bonkers.” But were she to go back again now, Murray could just jump on the plane. Australians are among citizens of almost 40 countries for which China now waives visas for business, tourism or family visits for up to four weeks. It’s