April 22 to April 28

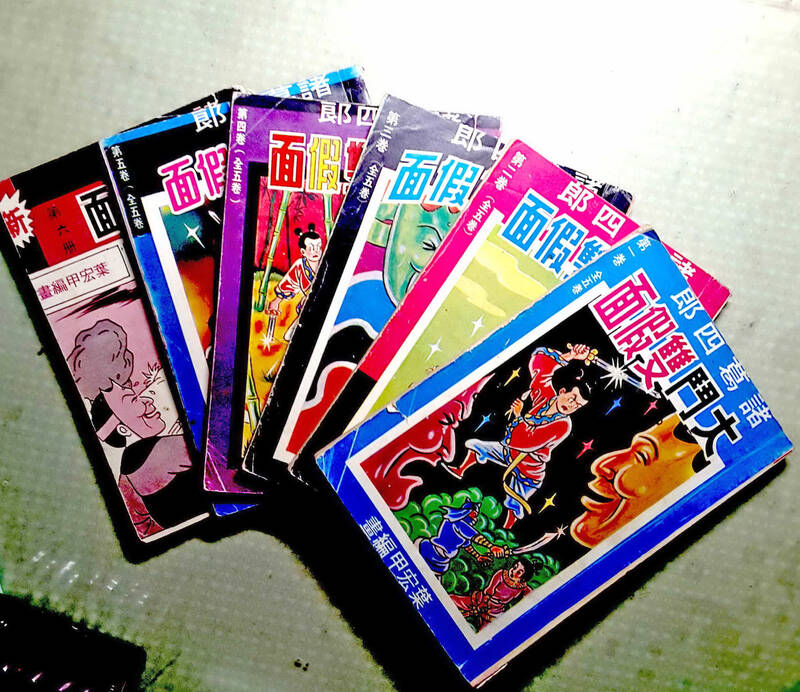

The true identity of the mastermind behind the Demon Gang (魔鬼黨) was undoubtedly on the minds of countless schoolchildren in late 1958. In the days leading up to the big reveal, more than 10,000 guesses were sent to Ta Hwa Publishing Co (大華文化社) for a chance to win prizes.

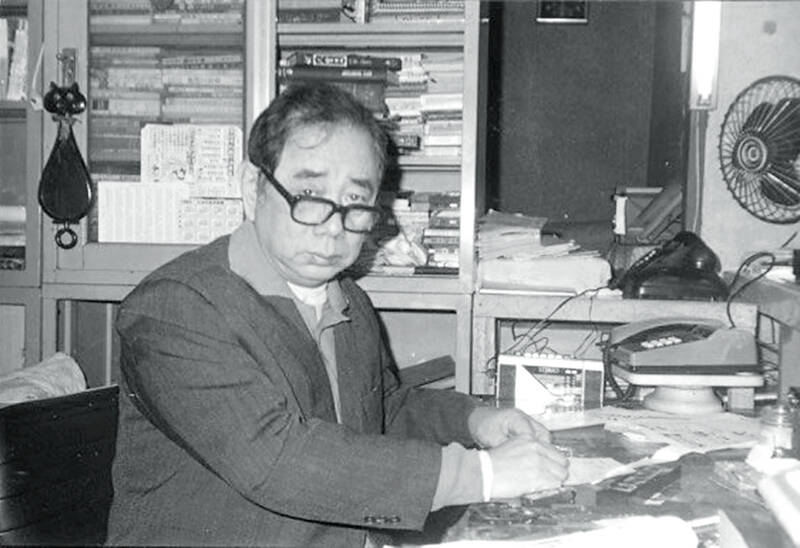

The smash success of the comic series Great Battle Against the Demon Gang (大戰魔鬼黨) came as a surprise to author Yeh Hung-chia (葉宏甲), who had long given up on his dream after being jailed for 10 months in 1947 over political cartoons.

Photo courtesy of Tong Nian Comics

Protagonist Zhuge Silang (諸葛四郎) is considered Taiwan’s first wuxia (武俠, martial arts) comic hero, battling evil and solving complex mysteries until the late 1960s, when the government clamped down on the comic book industry. The censorship law of 1967 greatly restricted the creativity of Yeh and other artists, leading many artists to give up while readers lost interest in the watered-down content.

Yeh persisted until 1973, but the financial burden was too great. He attempted a comeback during the Taiwanese comics resurgence in the late 1980s, but publishers rejected his style for being too old fashioned. This dealt a huge blow to his already frail body, and he died of a stroke on April 22, 1990 at the age of 67.

Fans still fondly remembered Yeh’s work, however, as he came in 7th in a poll of the most influential authors of the 1950s held by China Times (中國時報) in 1990, the only comic artist to make the list.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

ARTISTIC BEGINNINGS

Yeh was born on May 6, 1923 in Hsinchu, home to several other Taiwanese comic pioneers such as Chen Ting-kuo (陳定國) and Liu Hsing-chin (劉興欽, see “The Inventive Comic Artist,” April 9, 2023).

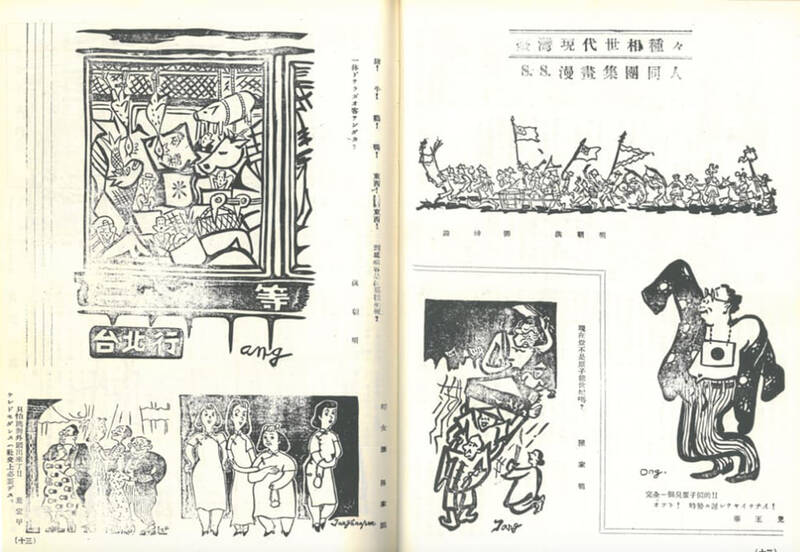

Yeh developed an early interest in art, and at the age of 13 his drawings were selected for public health and airstrike safety campaigns. The Japanese youth manga craze of the 1930s soon spread to Taiwan, and a 15-year-old Yeh joined a local program offered by a Japanese manga association. Members were given a special pin to wear as a badge of honor, and Yeh met his first co-creators after seeing them wearing the pin in the street. Together they formed the Niitaka Manga Club (新高漫畫集團), Taiwan’s first comics collective.

Photo courtesy of Yeh Chia-lung.

After World War II, the same group helped found the literary arts magazine Hsin Hsin (新新), which included a two-page satirical comics section that highlighted corruption, inflation and other problems during the first year of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule. The publication shut down after the 228 Incident of 1947, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed. Yeh was not targeted at first, but he was swept up in a police raid while visiting an artist friend’s house. Upon discovering his involvement with Hsin Hsin, the police threw Yeh in jail for 10 months.

MARTIAL ARTS HERO

For the next several years, Taiwan’s comic book scene was dominated by artists who arrived with the KMT from China, mostly creating anti-communist propaganda works. These pieces appeared in newspapers and were meant for adult readers.

hoto courtesy of Tong Nian Comics

Things changed in 1953 with the launch of the children’s magazine Hsueh You (學友), writes Yu Chia-jung (游家榮) in “Taiwan wuxia comics master Yeh Hung-chia” (臺灣武俠漫畫宗師:葉宏甲). The publishers realized that the comics section was the main draw, leading other magazines to follow suit. Most of this early content was pirated Japanese works.

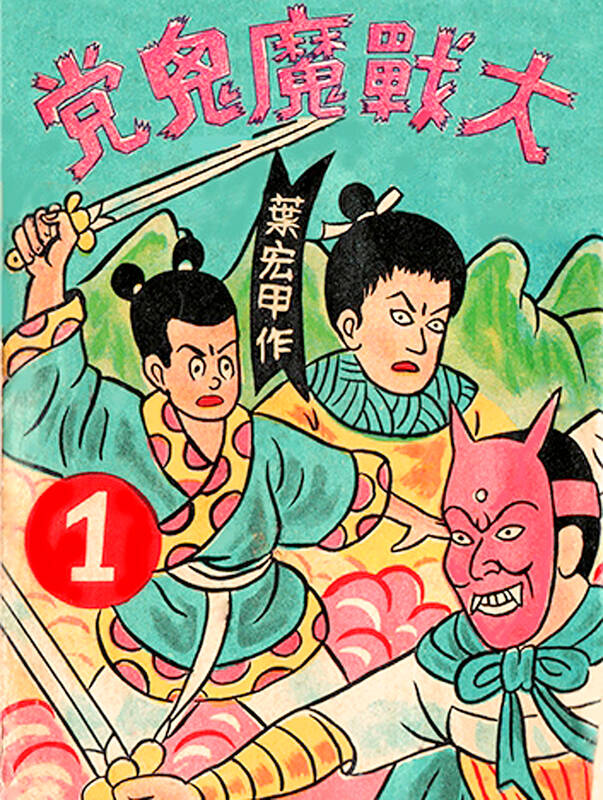

In 1956, Ta Hwa publisher Huang Tsung-kui (黃宗葵) asked Yeh, who ran his own design firm then, to contribute illustrations for a series of Chinese folk stories. They were pleased with his work, and let him take over a serialized comic of Journey to the West (西遊記) after the original artist abruptly quit. Two years later, Ta Hwa was preparing to launch Comics King (漫畫大王) — Taiwan’s first publication entirely devoted to the art form. Usually reserved and unassuming, Yeh boldly recommended himself as one of the main artists — and Zhuge Silang was born.

Yeh had only planned on drawing about 10 chapters, but the inpouring of fan mail compelled him to keep creating, sometimes working up to 14 hours a day. His pay rate soon doubled, and he was able to support his family by only drawing comics.

File photo

An amalgamation of two Chinese historical figures Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮) and Yang Silang (楊四郎), Zhuge Silang’s powers and virtues are rooted in the Chinese legends that Yeh voraciously read as a child. The setting is also a fictional version of ancient China. But the suspenseful, twisting plotlines reminiscent of detective novels, art style and certain character elements are clearly Japanese, writes Fan Kai-ting (范凱婷) in “Cultural imagination in the narrative texts of Taiwan wuxia after World War II” (戰後臺灣武俠敘事文本中的文化想像).

INDUSTRY DOWNFALL

The success of martial arts comics led to an explosion of works in the genre, but Yu writes that instead of diversifying, artists began copying each other and exaggerating the stories just to make a quick buck. This led to a steep decline in overall quality and increase in questionable content.

Although comics artists made good money, they were often reviled by society — especially parents, for distracting children from their studies. Many students lingered in darkly-lit book rental stores after school, and some even ran away into the mountains to find an immortal martial arts master to train with. Several never made it home.

A neighbor once told Yeh, “Your comics kill people!”

In 1962, the government began tightening restrictions on the industry. Still, Yeh persisted, launching his own publishing firm in 1965 and taking in numerous disciples, many who came from poor families. The 1967 comics censorship law dealt the final blow, as among other restrictions it banned artists from depicting any superhuman powers — which were the bread and butter of the genre.

For example, Zhuge Silang and his comrades no longer possessed mystical powers in the 1968 Storm in Snake Valley (蛇谷風雲), disappointing readers who eventually lost interest. Yeh shut down his studio in 1973.

Yeh suffered a serious car accident that same year, which led to a stroke that paralyzed half of his body. He continued to draw with a shaky hand with the support of his wife, and created covers for new editions of his previous work.

Interest in Zhuge Silang continued over the years, however, as evidenced in the 1978 live-action film Little Hero (諸葛四郎大鬥雙假面), and the 1985 Chinese Television System (華視) drama series. He and the Demon Gang were referenced in the classic 1982 song Childhood (童年) by Lo Ta-yu (羅大佑). Most recently, Yeh’s son Yeh Chia-lung (葉佳龍) produced a 3D animated version that hit the theaters in January 2022.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she