April 1 to April 7

Wiping away tears, the residents of Ljavek Village watched on Monday as excavators tore down the final house. With that, Kaohsiung metro area’s sole indigenous community — located (in)conveniently in the heart of the city’s business district — was no more.

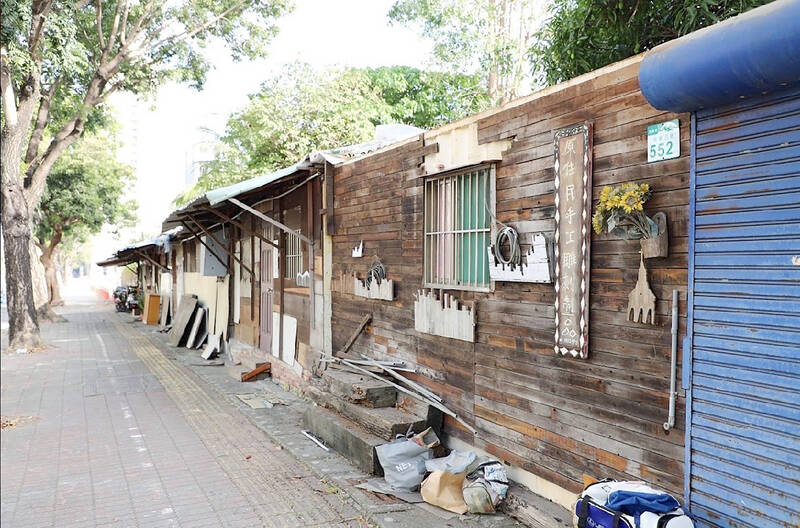

Ljavek, which means “place near the ocean” in Paiwan, was one of many urban indigenous communities that sprang up across Taiwan after World War II, when societal changes and industrialization pushed young people to seek work in the cities. Built along a shipping canal using scrap timber, bricks and iron sheets, it had up to 200 residents in its heyday.

Photo: Wang Jung-hsiang, Taipei Times

The village persisted as its surroundings drastically changed the canal was filled up in 1997 to become Jhonghua Fifth Road (中華五路), and the 2003 Asia New Bay (亞洲新灣區) development project eventually transformed the surrounding areas into shiny malls and high-rises. As such, many, including the media at that time, painted the community an eyesore and impediment to the city’s development.

In 1997, the city deemed Ljavek illegal despite the houses all having number plates and electric meters, and decided to demolish it — sparking a protracted struggle that culminated with the remaining residents winning a lawsuit against the government in 2022. After 33 negotiation sessions over the past year, the two sides agreed on a plan where villagers would build their own new houses in Fengshan District (鳳山) with government assistance, with space to continue their traditions and showcase their culture to visitors.

NEW URBAN HOME

Photo: CNA

In Taiwan Human Rights Journal article Displaced on their own land: Ljavek Village’s quest for survival in the city, Lin Tung (林彤) writes that the government’s indigenous assimilation policy in the 1950s hastened the erosion of traditional social structures and cemented mainstream capitalistic values into villages that were mostly self-sufficient in a natural economy.

These villages, however, did not have the resources to generate sufficient revenue under the new system, and their prospects were further limited by land use restrictions and other bureaucratic problems.

Most of Ljavek’s earliest residents were Paiwan from the villages of Kaviyangan, Qapedang and Makazayazaya in Pingtung County, who found work at the timber yards by the canal. They were later joined by Amis and Puyuma from Taitung. Companies had limited staff housing and most of them could not afford rent at first, so they simply began constructing simple abodes near their workplace.

Photo courtesy of Ljavek Self Help Association

For decades, the Paiwan maintained their traditional language and rituals and often returned home for ceremonies, Lin writes.

According to village records, residents successfully applied for electricity meters as early as May 1950, and began registering their household addresses in 1955. They paid property taxes, and, in 1985, they received standardized door plate numbers.

The filling of the canal was a turning point for the village, as it reduced their space and caused frequent floods. Hsu Yu-shan (許瑜珊) writes in Indigenous Documents (原住民文獻) that many residents elevated their houses to deal with the problem, leading someone to report their actions to the city. The government didn’t just deem the new additions illegal, however — they deemed the entire village illegal.

STRUGGLE TO STAY

In April 1997, residents received notice that their “illegal” village was to be immediately demolished. They protested and petitioned the government to let them stay, successfully delaying the process. In 1999, the city offered them public housing in Siaogang District (小港) at prorated rates.

Lin writes that the apartment-style buildings could not meet the villagers’ needs or lifestyles, nor did they have enough units to house all the residents. Plus, they were only guaranteed rental rights for eight years. In the end, only 13 households out of 40 agreed to relocate. The buildings were reportedly in bad condition, and many ended up moving back to Ljavek.

With the problem unresolved, the demolition was put on hold once more.

As the surrounding areas rapidly developed in the early 2000s, the city began pressuring the villagers to move again. Residents insisted that their houses were legal and refused, but facing immense pressure, they finally relented — but only if they could move together as a unit instead of being scattered to various locales like countless other displaced communities.

The case of the indigenous community of Cinemnemay in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) was of particular interest to the villagers. After resisting relocation for more than a decade, they accepted a plan to rebuild their village nearby with the costs split three ways between the villagers, the government and government-assisted loans. The process was by no means smooth, but they finally moved into their new homes in 2021 and completed a cultural park showcasing Amis culture last year.

Ljavek residents visited Cinemnemay in 2012 with city officials to learn about the process — but just a year later, the city’s public works bureau suddenly announced the village’s demolition within three months. Apparently, after the death of Formosa Plastics Group co-founder Wang Yung-ching (王永慶) in 2008, the company wanted to build a memorial park in the area where the billionaire got his start — and the proposed grounds included Ljavek.

NOT ILLEGAL

This event sparked the forming of the Ljavek Village Self Help Association and drew activists, scholars and students to the cause. But after two fires in 2015 and 2016 destroyed a dozen houses, which the residents were forbidden from rebuilding and unable to withstand the stress of the prolonged resistance and constant fear of ending up homeless, 19 households agreed to move to public housing in 2017.

Things came to a head when five households who agreed to move had yet to tear down their residences by the deadline of March 20, 2018. According to Lin, in one household, the eldest son had signed the relocation agreement but the elderly parents disagreed and remained. Another house was vacated, but then occupied by a family who lost their house to a fire. Another resident thought the agreement he signed was just a poll.

In the morning of April 2, 2018, the Kaohsiung City Government sent 300 police officers to block off the roads, evacuate the residents and razed a total of 11 houses. The villagers had enough and sued the government, and after a lengthy court battle lasting three years, they won.

The city agreed not to appeal and began seriously negotiating with the villagers on a suitable relocation plan, finally drawing the battle to a close.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern