March 18 to March 24

Yasushi Noro knew that it was not the right time to scale Hehuan Mountain (合歡). It was March 1913 and the weather was still bitingly cold at high altitudes. But he knew he couldn’t afford to wait, either.

Launched in 1910, the Japanese colonial government’s “five year plan to govern the savages” was going well. After numerous bloody battles, they had subdued almost all of the indigenous peoples in northeastern Taiwan, save for the Truku who held strong to their territory around the Liwu River (立霧溪) and Mugua River (木瓜溪) basins in today’s Hualien County (花蓮).

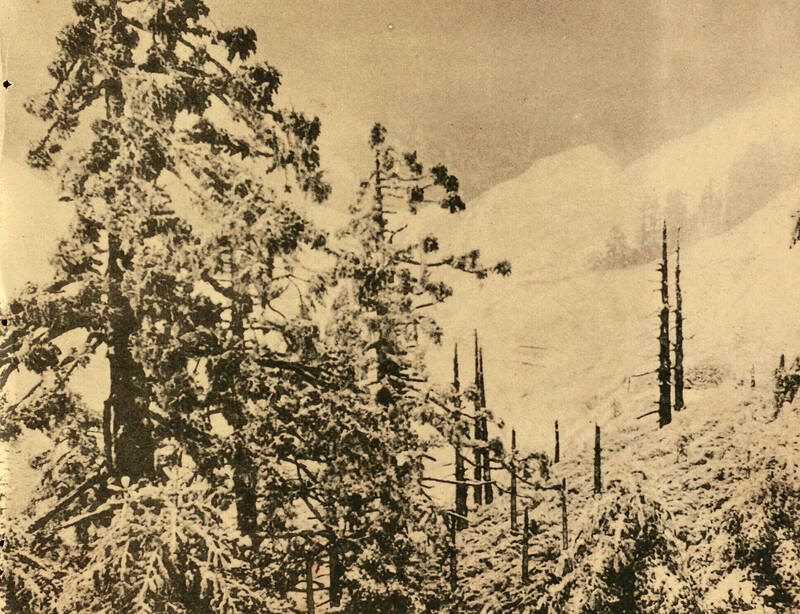

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The Japanese forces were somewhat familiar with lowland terrain, but even after 17 years of ruling Taiwan, they knew nothing of the Truku areas. After several failed survey attempts, time was running out with orders to complete the plan within the allotted time frame.

After praying at the Taiwan Shinto Shrine in Taipei, Noro, who was the expedition’s chief surveyor, led the 286-strong team from Nantou County’s Puli Township (埔里) toward the high mountains of the north.

It was a disaster. After scaling the peak, the group’s camp was pummeled by a massive storm that brought wind, rain and even marble-sized hail. The official death toll was 89 — all of them Taiwanese.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Even though the Yasushi Noro Incident remains the deadliest mountaineering disaster in Taiwan’s history, remarkably, Noro was rewarded as there were no Japanese casualties.

He tried again in October and succeeded, paving the way for the 1914 Truku War.

MAPPING INDIGENOUS LAND

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Noro first arrived in Taiwan in 1899 as a survey technician. By 1902, he was supervising land surveying operations across the entire island. After assuming his post in 1906, new governor-general Samata Sakuma vowed to bring the remaining hostile indigenous areas under colonial control, as they contained valuable timber and camphor resources the Japanese hoped to exploit.

Noro worked directly under Sakuma in the Indigenous Affairs Agency. His first official expedition to indigenous lands was in November 1908, when they scaled Niitaka Mountain, known today as Yushan or Jade Mountain (玉山). It was during this trip that the Japanese realized Yushan belonged to a separate mountain range from the Central Mountain Range.

Noro first attempted to survey Hehuan Mountain in 1910, but turned back due to a storm. Another team led by police officers investigated the Liwu River basin in December 1911. But halfway into the journey they encountered about 40 Truku warriors who blocked their way. Since they were not familiar with the area, the Japanese opted to retreat.

In September 1912, a team climbed Nenggao Mountain (能高) and recorded the Truku villages along the eastern part of Mugua River and the paths the inhabitants used to traverse the thick forest. Then, they climbed the main peak of Chilai Mountain (奇萊山) and mapped the surrounding landscape.

However, they were stopped from going further east by representatives of the Butulan group of Truku, who refused to negotiate or allow the Japanese to meet their village chiefs.

PRECARIOUS ASCENT

The expedition set out in March 1913. It included 14 Japanese officers, 55 Japanese patrolmen and 64 indigenous guides as well as Han Taiwanese porters and frontier guards. The indigenous guides were led by Katsuzaburo Kondo, who moved to Puli in 1896 to trade with the indigenous Seediq and married the daughter of a local chief. In the early days, when few Japanese dared venture into hostile indigenous territory, Kondo was accepted into Seediq society and often acted as the main go-between for the government and different indigenous groups.

They had just reached Yingfeng (櫻峰) police station west of Hehuan Mountain on March 17, when it began to pour. They were forced to camp in the station for two days, and about 40 to 50 porters and frontier guards could no longer stand the cold and slipped away during the night.

The sky cleared on March 20, and porters arrived with fresh supplies. Unfortunately, these porters were forced to join the march up the mountain to replace those who fled, despite them not wearing the proper clothing.

Around noon the next day, the indigenous vanguards sent word that it was extremely cold and snowy on the main peak and advised the group to seek shelter in a forest on the side of the east peak. Kondo personally headed back to convince Noro, but Noro insisted on camping on the top. He was worried that the Truku would attack them in the forest, and preferred to stay on the peak where visibility was better.

Both sides refused to budge, and in the end Noro allowed the indigenous team to stay in the forest and meet them on the peak the following morning. Noro’s group reached the top by 4pm and set up camp.

DEADLY WINDS

They barely had an hour to rest.

The northeastern wind had been increasing in force under pressure as it traversed the narrow Liwu River valley up Hehuan Mountain. Upon reaching the top, with no barriers on either side, it exploded exponentially, hitting the camp with full force.

The entire campsite was destroyed, the team members futilely resisting the elements with soaking wet blankets. Then the hail started falling, and the temperature fell below zero. Most of the Han Taiwanese came from the plains and had never experienced such cold before, faring visibly worse than the Japanese. Many tried to flee in the dark despite Noro’s attempt to stop them.

The storm lasted until dawn. Between 50 and 60 people were missing, and they had lost everything except for the surveying equipment. Noro had no choice but to call off the expedition.

As the survivors descended, they found bodies scattered along the path, belonging to those who tried to leave during the night. A dozen fortunate ones were rescued by the indigenous team. More collapsed along the way.

Upon returning, Noro asked to be punished, but he was rewarded for “responding appropriately during disaster and safeguarding the lives of the team’s members.” Apparently, only Japanese souls counted.

Rescuers were able to retrieve 34 bodies. The victims’ families were compensated, but no plaque was erected and their names remain unknown.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

President William Lai’s (賴清德) March 13 national security speech marked a turning point. He signaled that the government was finally getting serious about a whole-of-society approach to defending the nation. The presidential office summarized his speech succinctly: “President Lai introduced 17 major strategies to respond to five major national security and united front threats Taiwan now faces: China’s threat to national sovereignty, its threats from infiltration and espionage activities targeting Taiwan’s military, its threats aimed at obscuring the national identity of the people of Taiwan, its threats from united front infiltration into Taiwanese society through cross-strait exchanges, and its threats from

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at