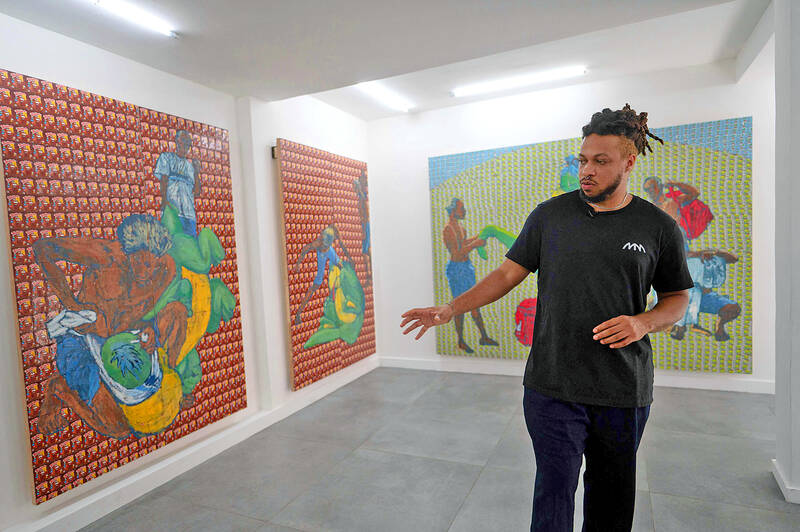

Like in most cities, Rio’s galleries are concentrated in its affluent neighborhoods. But artists like Maxwell Alexandre are trying to change that, hoping to “give access to what was previously the art of the bourgeoisie, something exclusive,” the 33-year-old said.

Alexandre grew up in the shantytown of Rocinha, Brazil’s second most populous favela, and where he opened the Pavilhao 2 display space last year. At the moment, he is exhibiting a collection of his own works that last year was on display at a gallery in the exclusive sixth arrondissement of Paris, France.

Entitled Entrega: one planet. one health, the exhibit includes paintings of daily life in Rocinha.

Photo: AFP

A series of three works shows children dressed in school uniforms carrying bags from a food delivery company: a commentary on pervasive child labor.

Another aim of Alexandre — who has also exhibited in Spain and the US — is to make favela residents art owners.

“I want people who live in the favela to see my work not only in the gallery but also at home,” he said.

Photo: AFP

Alexandre is selling his works at the below-market price of about 1,000 reais (US$200) apiece though even this may be a high ask of many.

ART POWER

The gallery also aims to draw visitors from outside, such as 45-year-old teacher Mariana Furlonis, who said: “It’s great, because art is usually very elitist.”

Alexandre acknowledges that most visitors do not come from the favela, whose impoverished inhabitants have other, more pressing priorities.

But though he is often advised to focus his efforts on such artistic hubs as Berlin or New York, Alexandre prefers to stay in Rio, where he says his creativity is inspired by the heat, the violence, the omnipresent poverty.

About 30 kilometers away, fellow artist Allan Weber, 31, opened a gallery in his childhood favela, Cinco Bocas, in 2020.

His works had recently been exhibited at the Miami contemporary art fair Art Basel.

Back in Rio, he uses his gallery to give exposure to lesser-known local artists.

“It’s a place of exchange between the favela and people who come from elsewhere,” he said.

His target clientele are people like himself who grow up without access to downtown museums, but also more affluent friends reluctant to visit the favelas, frequent targets of heavy-handed police operations.

“I spent all my childhood seeing weapons, and thanks to art, I was able to give them a new meaning,” Weber said.

One of his creations is an assault rifle made from camera parts.

‘NO PLACES LIKE THESE’

Since last September, Weber’s gallery has hosted an exhibition entitled “To de Pe” (I am standing) by 22-year-old Cassio Luis Brito da Silva.

The youngster’s creations include photos of evenings of “Baile funk,” a musical style born in the favelas, and sculptures made with cigarettes. Da Silva, a favela resident himself, said being exposed to the work of other artists at the gallery serves as an inspiration.

“It is wonderful to see people like me exhibit in this place,” he says.

At Cinco Bocas, Weber encourages visits from disadvantaged youngsters from the favela.

Cintia Santos de Lima, 35, says her autistic son has benefited from the initiative.

“Before, he didn’t want to go out. It is good for us because in the community there are no places like these.”

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern