There’s a temple fair outside the Sanzhong Temple and the residents of Shuangsi (雙溪), a rural village in New Taipei City, have gathered for a banquet. Fire-crackers are lit streetside and there’s exited chatter among the congregation, mostly in Taiwanese.

“They’re venerating a Song Dynasty patriot, Wen Tianxiang (文天祥)” says M.A. Aldrich, who first visited this corner of northeast Taiwan in 1985 and now calls Shuangsi home.

“I decided to visit Taiwan after a challenging student exchange year in Gwangju, South Korea. It was within a short time of the Gwangju Massacre in 1979 and there had been a lot of upheaval. It was difficult to drink in higher traditional Korean culture with all that negativity floating in the air. So that was the reason why I took a one month trip to Taiwan. I was totally charmed. I was, I admit, better at Chinese than I was at Korean. I based myself in Taipei but travelled around. And I remember being taken by Shuangsi, which I first passed by on the train.”

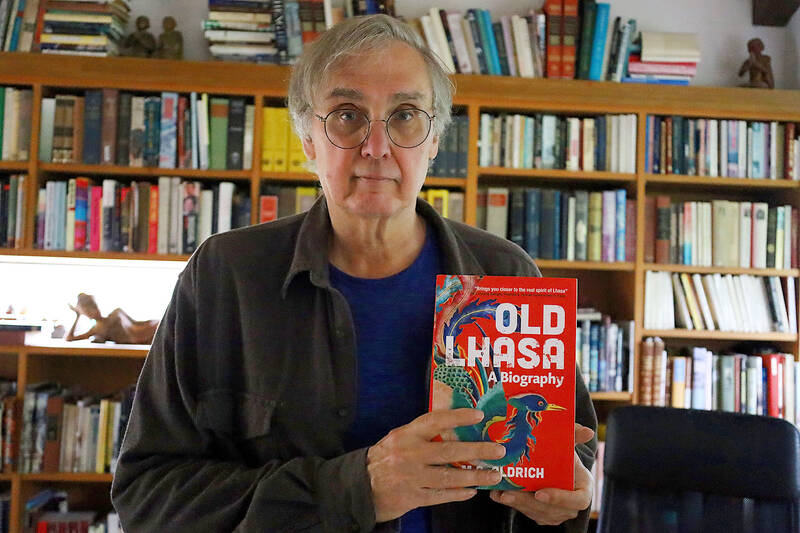

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

Aldrich returned in the US to study law at Columbia University but came back to Taiwan in 1987.

“I realized that once I’d graduated, I wouldn’t have the opportunity to focus on language again, so I took a leave of absence to work as a legal clerk at Ding & Ding Law Offices in Taipei. I loved the job and found the rhythm and flow of life rapturing. Of course Taipei was far less cosmopolitan than it is now. There was only one Indian restaurant and three Vietnamese restaurants. It has changed a lot, with tons of things for young people to do today, rock concerts, exhibitions, you name it. I went to temple festivals and celebrated traditional holidays, visited bookstores to pick up copies of Chinese classics. And I got to witness the lifting of martial law and Taiwan’s transition into democracy.”

Aldrich didn’t just fall in love with Formosa.

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

“That’s when I met my wife-to-be Chuang Mei-chih who was working in a travel agents at the time. I asked her where she was from and she said, ‘you’ve probably never heard of it, it’s a place called Shaungsi.’ I suppose you could say it was one of the rare real life examples of yuanfen (緣分),” he says, applying the Chinese word for “destiny.”

Aldrich takes me on short tour of his adopted hometown, along Shuangsi Old Street (雙溪老街) where a spattering of historic merchant buildings have been maintained for posterity, some dating back to the Qing Dynasty.

“Before they opened the railway, the center of town would have been here by the riverfront,” Aldrich says, pointing to old wharfs along the Shuang River where boatmen would have arrived, their river junks heavy with rice or coal. “Sometimes I like to imagine what life had been like all those years ago.”

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

FROM LAWYER TO SCRIBE

Aldrich lives a short drive away, in a two-story village house fronted by an ornate Japanese-style garden.

“We came here in 2015. I’ve worked in some challenging places over the years, dragging my wife with me. We decided it was time to come home.”

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

This is no exaggeration. After a stint in California, Aldrich moved to Hong Kong in 1992, a time he describes as “exhilarating.” His work required frequent business trips to the People’s Republic of China and in 1993 he moved to Beijing for a period, returning to live there in 2005. While working in northern China he found time to pen two books, The Search for a Vanishing Beijing (2006) about the fast-disappearing historic areas of the capital and, with Lukas Nikol, The Perfumed Palace (2009), concerning Beijing’s Muslim quarter.

In 2009, a Mongolian law firm requested a senior lawyer who’d be willing to help them improve their service standards. Aldrich signed-up, at first temporarily, but ended up staying six years in remote Ulaanbaatar.

Since taking early retirement, however, Aldrich keeps himself busy with his passion projects.

Photo: Thomas Bird, Taipei Times

“When my wife goes out to play mahjong you’ll probably find me here,” he says, guiding me through a sizable library of books, mostly on Asia, in his private study. “That’s if I’m not brewing beer,” he adds, alluding to his hobby microbrewing ales and pilsners.

As he’s out of homebrew, he opens a bottle of single-malt Kavalan whisky instead, which he sips beside his log wood fireplace in the company of his dog Pooch.

“Except to walk the dog, I don’t get out much.”

Instead, Aldrich writes. It was in his Shuangsi study that he completed his third book Ulaanbaatar: Beyond Water and Grass (2019), which he says led him to his latest literary endeavor Old Lhasa: A Biography, which was published last year by Taiwan-based Camphor Press to critical acclaim.

“When I was writing about Beijing I discovered the remnants of the older Mongolian city so that led naturally to Ulaanbaatar. After I finished my book about Ulaanbaatar it occurred to me the city seemed to be an alternative reality for Lhasa, that is, if Tibet had avoided absorption into the Chinese state like Mongolia had.”

This sentiment Aldrich expresses early on in the book, “the juniper incense wafting from temples, and the drawings of endless knot on wooden doors enclosing khasas (Mongolian courtyards) were echoes of distant Tibet.”

The impetus to write about Lhasa, he writes, “was irresistible.”

ROOFTOP OF THE WORLD

Researching a city sometimes dubbed the real “forbidden city” due to Beijing’s ironfisted control of Tibet since 1950, was not without its challenges and Aldrich had to apply for travel permits and sign up for officially sanctioned tours.

“I had four hundred pages of notes before I went so I knew where some of the significant temples would be before I even set eyes on them.”

A total of three trips were made before COVID-19 saw Tibet closed to foreign tourists.

“I suppose you could say I was ready for lockdown,” he says.

The result is as much a guide through time as place. It’s a chunky 611 pages but this is no academic treatise and is designed to transport an armchair traveler through “one of Asia’s great cultural capitals” as well as help a visitor to Lhasa understand what they see.

“One of the best compliments I have had is that people say it’s readable,” Aldrich says with a chuckle.

To give each sacred site context, each chapter weaves in narratives from history, be it the life of the Buddha in India or the British expedition led by Francis Younghusband in 1903. Photographs and illustrations throughout the book compliment the text.

Aldrich says he took inspiration from “Liza Picard who writes superb books about London’s history and culture,” when writing Old Lhasa: A Biography.

On the way back to town, Aldrich tells me of his next great literary journey: “There’s a topic that fascinates me, it’s called New Qing Studies and is essentially an attempt to try to resurrect the role of the Manchu people, to give them a less Han infused interpretation of history. The Manchus are very enigmatic. So what I’d like to do is to write a travelogue about visiting the most famous sites associated with them.”

Shuangsi Station, quaint and mountain-framed, seems a world away from the Gandan Monastery in Mongolia or the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. But it’s clearly a place where Aldrich can allow his imagination to fly freely around Asia, while his boots remain firmly on the ground.

“Of everywhere I’ve lived, I’ve liked it here best. I remember reading in one of the guidebooks there’s nothing much to do around Shuangsi. Maybe they’re right, but well, there’s something about the quietude.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,