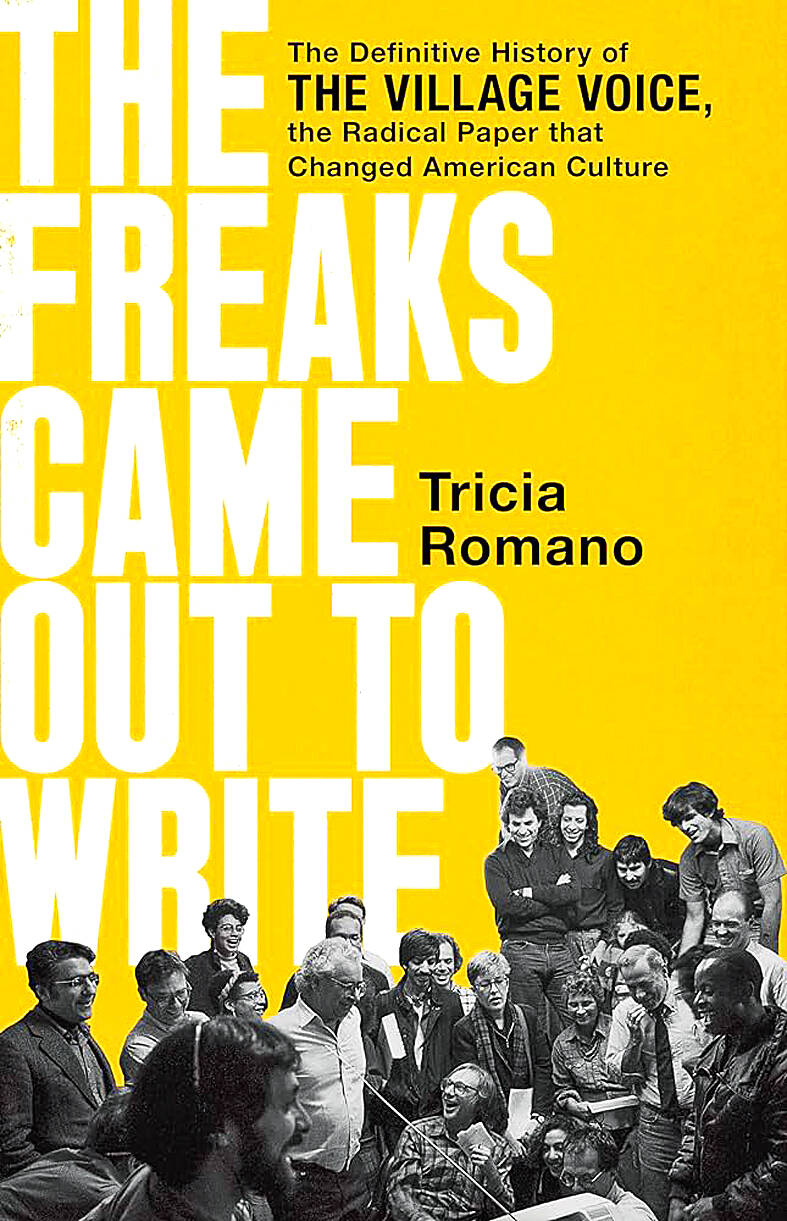

Midway between the glitz of Times Square and the grind of Wall Street, Greenwich Village used to be New York’s ulterior zone, a refuge for artists and agitators, dropouts and sexual dissidents. With the New York Times established as the city’s greyly official almanac, in 1955 this bohemian enclave acquired its own parochial weekly, the Village Voice. The rowdy, raucous Voice deserved its name, and now, following its closure in 2018 (it has since been revived as a quarterly), it has an appropriately oral history. The collage of interviews in The Freaks Came Out to Write extends from the paper’s idealistic beginnings to its tawdry decline, when it scavenged for funds by running sleazy ads for massage parlors.

The Voice’s origins were proudly amateurish. One early contributor was a homeless man recruited from a local street; equipment consisted of two battered typewriters, an ink-splattering mimeograph machine and a waste paper basket for rejected submissions. Morale spiked when a staff member discovered that dried pods used in fancy flower arrangements contained opium, which was boiled up in the office when the time came for a coffee break. Editorial standards hardly matched the pedantic correctness of the New Yorker. Norman Mailer, a columnist for a while, loudly berated a Voice copytaker who mistook “nuance” for “nuisance” and ordered the cowering menial to “take your thumb out of your asshole!”

GONZO JOURNALISTS

Behavior like this was the rule at the ungenteel Voice. An investigative reporter joined forces with teenage gangs on looting expeditions, and during a riot at Tompkins Square in the East Village another journalist relished the wet but effective weaponry used by squatters, who bagged their own urine, added donations from stray cats and dropped the plastic sacks from rooftops on to the police below.

“Cops will run away from cat urine,” we’re assured. “It’s a lot better than a gun.”

At the New York Times, someone else reflects, people stabbed you in the back, whereas the more upfront writers at the Voice aimed for the chest. Notoriously competitive, contributors denounced one another in abusive slogans scrawled on the walls of the office toilet. Occasionally there were punch-ups in the newsroom.

“You may kick my ass,” the music critic Stanley Crouch warned a colleague, “but I’m going to hurt you.”

If pinioned to prevent him from using his fists, Crouch savaged his opponents with his teeth instead. A battle of the sexes was fought more peaceably in an exchange of epithets. Mailer snarled that the Voice’s feminist contributors wrote “like very tough faggots;” one of the women snapped back by denouncing Mailer and the jazz critic Nat Hentoff as “old-school male fuckheads” or “absolute oppositional pieces of shit.”

FLASHY, QUIRKY

The Village’s voices were journalists of a new kind, flashy and often crazily quirky. Jill Johnston wrote rhapsodies about female desire in an unpunctuated flux that mimicked Molly Bloom’s stream of consciousness in Joyce’s Ulysses. Greg Tate devised a critical method for analyzing Black culture that he called “Yo, Hermeneutics.” The sports reporter Robert Ward found himself speechless when the baseball team he favored lost the World Series, and began his column with an elongated moan followed by a smattering of curses: “O h h h h h h h h h h h h h h h. Shiiiitttttttttt. Jesus Fucking Shit. Oh Christ. Agh. Arg.”

Cutting through this vocal and verbal babble, the most quietly eloquent testimony is a moment of suppressed terror recalled by Michael Musto, whose job was to keep the Voice topped up with high-pitched showbiz gossip. During the Aids epidemic, Musto recalls that he showered in the dark, afraid of discovering a potentially fatal lesion as he soaped his body.

“The Voice saved the Village,” boasts one of its last editors. Yes, during the 1950s its advocacy helped defeat a scheme to level the area’s crooked, congested maze in order to send a four-lane expressway careening across Manhattan. But although the Village was physically preserved, social and economic changes invisibly overtook it and at last these neutered the radical Voice. Property developers drove out the impecunious artists; yuppies occupied the lofts and studios they vacated. Rudy Giuliani’s regime at City Hall enforced a pious ordinance that banned gay bars and sex shops situated near churches. The Meatpacking district, where the streets until recently were puddled with blood from butchered carcasses, now houses showrooms for Rolex, Apple, Moschino and — taking the prize as most dizzily pretentious — a brand of apparel entitled Theory.

The founders of the Village Voice thought of it, Ed Fancher says, as “a religious thing”, leading a progressive crusade. These days the local religion is consumerism, not liberal reform: the Village has been recast as a shopping mall where the only voices to be heard are a hubbub of inducements to buy. The Freaks Came Out to Write is a rueful elegy for rawer, cheaper better days.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the