Among the immigrants and expatriates who’ve lived in Taiwan for years, there are hundreds and perhaps thousands who’d very much like to cement their status here and their connection with the country by becoming naturalized citizens — but feel they cannot proceed under current rules.

They meet the residency, good conduct, language proficiency and other requirements for citizenship, yet they regard one part of the naturalization process as a dealbreaker. The demand, set out in Article 9 of the Nationality Act (國籍法), that aliens “applying for naturalization shall provide a certificate of loss of original nationality within one year from the day of approval of naturalization,” is widely seen as an unreasonable stipulation that new citizens sever ties with their home country.

Giving up one’s original citizenship may mean: Having to obtain a visa before traveling to the country where one was born; not being able to spend months at a time there, and thus unable to care for aged parents; unfavorable taxation consequences; and not being able to own or inherit property in that country.

Photo: Doruk Sargin

Some foreign citizens are able to naturalize as Taiwanese without relinquishing their previous nationality. Japanese individuals have successfully completed the process after submitting paperwork from their home country confirming that their application to renounce Japanese citizenship wasn’t approved. And because they’re governed by different rules, holders of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region or China passports needn’t give up those travel documents. Chinese citizens, however, must renounce their household registration in China. (It seems they can later restore their China household registration, but doing so would likely result in losing their Taiwan ID card and household registration.)

What’s more, people from countries where renunciation is never permitted (such as Argentina) and those who qualify as “high-level professionals” needn’t prove they’ve given up their original nationality. But the pathway to citizenship for those in the latter category is notoriously narrow: Between 2016 and the end of last year, it resulted in just 281 new Taiwan citizens.

DOUBLE STANDARD

Photo: Reuters

Taiwan, officially known as the Republic of China (ROC) isn’t unusual in insisting that new citizens have just one nationality. Several countries don’t allow their adult citizens to hold other nationalities. In China, Japan and elsewhere, the prohibition applies in both directions. In Taiwan, however, there’s a blatant double standard that exists nowhere else in the world, and which angers many would-be citizens.

In contrast with the renunciation requirement that’s imposed on the majority of newcomers who try to naturalize, Taiwanese who move abroad can continue to enjoy the benefits of holding a Taiwan passport, even if they acquire foreign nationality.

So long as they maintain their household registration in Taiwan, they can vote here and stay enrolled in the National Health Insurance scheme. Taiwanese who move back to Taiwan can keep their second passports, unless they stand for elected office, or accept a senior civil service or political-appointee position.

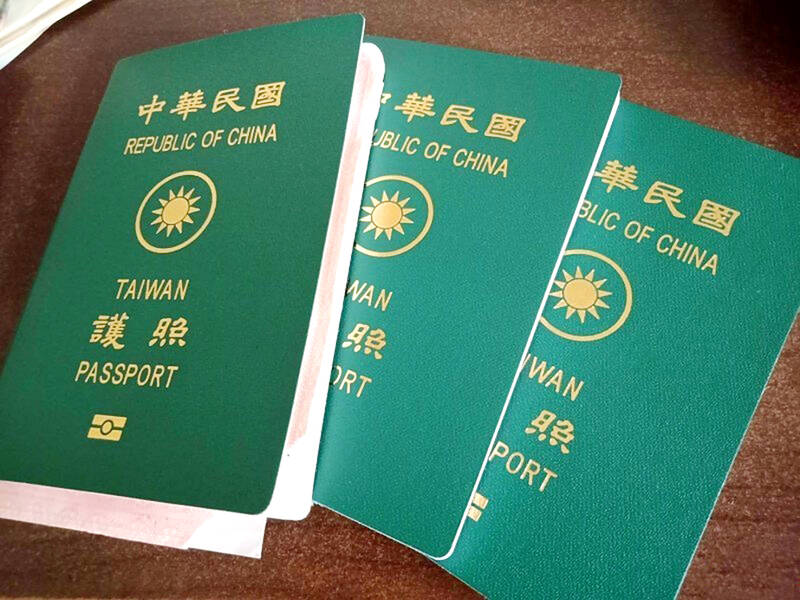

Photo: TT file photo

Asked if he knows why Taiwan has ended up with this peculiar legal asymmetry, David Chang (張代偉), secretary-general of Crossroads — an NGO that aims to facilitate exchanges of talent between local and international communities “for the promotion of cultural, academic and industry diversification” — says he can’t point to any one reason with certainty.

“I think it stems from identity, and an expectation that people declare loyalty by relinquishing their original nationality,” he speculates, adding: “Of course, if you pointed out that, according to such logic, Taiwanese living overseas should give up their Taiwan passports, you’d probably be met with silence.”

He thinks there could also be a fear that, if substantial numbers of “non-Taiwanese” become citizens and take part in the political process, “the system of power might be disturbed. For a country that’s not used to immigration, it’s understandable that people might feel this way.”

At the end of last year, 851,932 aliens were resident in Taiwan. President-elect William Lai’s (賴清德) margin of victory in last month’s presidential election was 914,998. According to a survey last year of Taiwan-based foreign professionals by Talent Taiwan (a unit of the National Development Council), 62 percent of the 1,000-plus respondents don’t plan to apply for citizenship, but they’d consider it if they could also retain their current passports.

CHALLENGES

Taiwan faces multiple challenges, including a low birth rate, an aging population and global competition for talent, Chang says.

“A healthy circulation of talent should consist of a standardized and holistic process for attracting, integrating and cultivating talent to boost the workforce — in essence, bringing in new talents for the purpose of absorbing and ‘home-growing’ the country’s workforce. However, by holding immigrants at arm’s length by making it challenging for them and their children to become fully vested citizens, immigration efforts only serve as short-term ‘bandages’ to the hemorrhaging of talent,” he says, before adding: “But how can we convince people who’ve not been exposed to diversity that this is the case?”

Whatever its origins, the “dual citizenship for us, but not for you” reality is galling, to put it mildly, says a Taichung-based bike industry entrepreneur who prefers to remain anonymous. “In my opinion, insisting on single citizenship for everyone — like Singapore does — is much more reasonable,” he says.

The first business he established employed 50 people before he was bought out by his partner. His current firm has 15 employees. He pays taxes and owns property in Taiwan. His wife and children are Taiwanese. “But I’m not good enough to be a citizen? I’m a little bitter about that,” says the APRC (alien permanent resident certificate) holder.

Asked about his motives, he replies: “I’d really love to vote in Taiwan. I’ve spent almost as much time here as in my home country. I’d love to have my say in the democratic process.”

In 2017, he submitted documents and letters of recommendation in a bid to become naturalized on the strength of his contributions to the country in which he’s now lived for 18 years. His application was rejected.

He’s since considered naturalizing via the conventional route, yet he remains reluctant to disown his original citizenship. One reason is emotional. Despite his strong commitment to Taiwan, and recent turmoil “back home,” he still feels an attachment to the Southern Hemisphere country in which he grew up.

The other is practical. In addition to being Taiwanese, his children are citizens of his home country. But if he renounced his current citizenship to satisfy Taiwan’s rules, they’d lose their second passports. “If it didn’t impact them, I’d probably renounce and then try to reclaim my original citizenship,” he says.

LOYAL CITIZENS?

If the renunciation provision is supposed to ensure that new citizens are loyal, by ensuring they’ve nowhere else to go, there are at least two reasons why it’s unlikely to be effective.

First, whoever drafted the rule didn’t seem to contemplate the possibility that an applicant may already hold more than one passport. Individuals who already have dual nationality aren’t required to give up both, just the one they used to establish themselves in Taiwan.

Second, many countries allow those who’ve quit the citizenship they were born with to restore it at a later date. This is straightforward for someone who used to be Australian, British, South African, Vietnamese or a citizen of the Philippines. For those who relinquished a US or Pakistani passport, it’s much more difficult, but sometimes possible.

Guidance published by the British government advises: “You have a right (once only) to be registered as a British citizen if you previously renounced British citizenship in order to keep or acquire another citizenship.” If the applicant has already exercised that right, they can reapply, but reregistering as a British citizen will depend on the discretion of officials.

A newly naturalized citizen of Taiwan may get their old passport back even before submitting the “certificate of loss of original nationality” required by Article 9. At least one person from a Western country is doing this.

Explaining that he merely needs to provide proof that he renounced his previous citizenship within a year of naturalizing, otherwise the naturalization will be revoked and his Taiwan passport canceled, he tells the Taipei Times that he’s already reinstated his original citizenship and will get a new passport from his country of birth before returning to Taiwan.

The man — who’s been advised to remain anonymous, because his actions could be perceived as making a mockery of the rules and the bureaucrats who apply them — says the entire relinquish-and-restore process is costing him close to NT$20,000.

The financial cost of giving up one’s citizenship may deter some would-be Taiwanese. To renounce, New Zealanders need to pay their government NZ$398.60 (NT$7,764). For Americans, the fee was recently reduced from US$2,350 (NT$74,024) to US$450 (NT$14,175). One unintended consequence of the renunciation obligation is that it transfers money from Taiwan households to foreign governments.

Making naturalization difficult hampers foreign residents who’d otherwise invest in their lives here. A woman from Europe who’s working in Taiwan, and stresses that she’ll never become Taiwanese if it means giving up her original passport, says recently she wanted to buy a property, but couldn’t because local banks wouldn’t lend her enough money.

Her bank told her that, if she’d been a naturalized citizen of Taiwan, they’d be happy to arrange a mortgage of 85 to 90 percent of the property’s value, “but since I’m still a foreigner, despite having a high income, they could only offer 60 or 70 percent.”

In expatriate circles, the reluctance of local banks to issue credit cards to non-citizens who’ve lived here for decades is a perennial complaint.

“I’d like Taiwan to make it easier to express support for this country,” says the bicycle entrepreneur in Taichung. “The amount of international goodwill that Taiwan enjoys is massive and growing. It could only benefit Taiwan to have a greater number of white-collar foreign-born citizens from a range of countries, adding skills and diversity to the society.”

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of