In King Lear, confronted with the figure of his cruelly blinded father, Edgar wonders whether matters are as bad as they imaginably could be. He concludes, however, that “the worst is not/So long as we can say “This is the worst.”’ The very fact that he has language, and the capacity for judgment, is itself proof that he has more to lose. Edgar’s words, in this most archaic of Shakespeare’s plays, feel horribly prophetic of the slaughter bench of modern history, as if the events of the 20th century were designed to test them. Is this the worst of which human beings are capable? Is this? Is this?

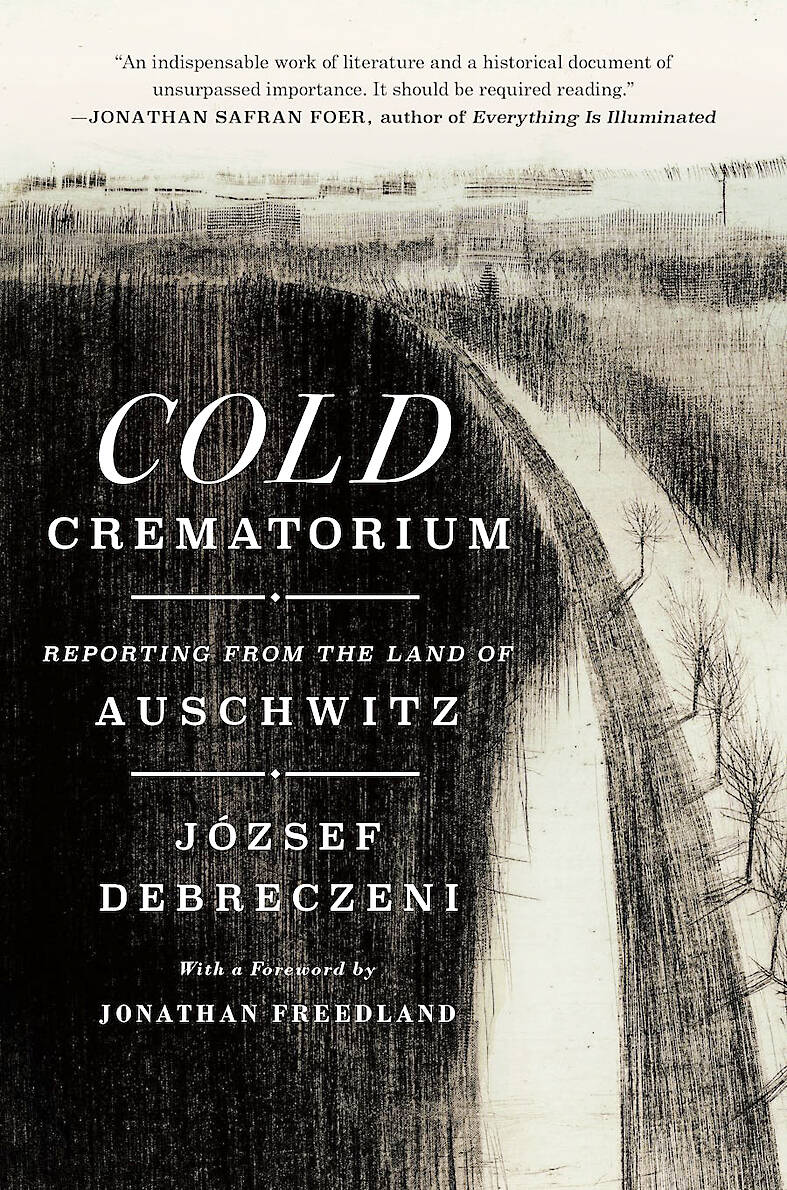

Jozsef Debreczeni’s memoir of the Nazi death camps, translated into English from Hungarian for the first time, frequently echoes Edgar’s claim. After being moved from “the capital of the Great Land of Auschwitz” to one of the networks of sub-camps, Eule, he discovers that he is to be moved again: “Surely I couldn’t end up in a place much worse, I thought — and how tragically wrong I was.”

By the end of his remarkable set of observational writings, the word “worse” has lost all meaning; comparing the depths of human experiences of depravity and suffering feels obscene in itself. Is typhoid worse than starvation? Is being crushed to death while mining a subterranean tunnel worse than wasting away in a pool of one’s own filth?

By the end of his remarkable set of observational writings, the word “worse” has lost all meaning

Debreczeni, an eminent journalist, thwarts any such comparisons by allowing the events that unfold to hover before the reader in the astonishing equipoise of his prose. In an excruciating moment for which the phrase “gallows humor” seems entirely inadequate, he tells us that the doctors’ nightly cry — “Report the dead!” — was responded to by “the more jocular among us” with “Report if you’re dead!”

Debreczeni’s account manages to make something of this unthinkable jocularity, to report the dead and to report his own life-in-death. He captures detail after harrowing detail. The old carpenter, Mr Mandel, an erstwhile chain-smoker whose hands still “moved mechanically, as if holding a cigarette” in the cattle car en route to Auschwitz. The former Czech army officer, Feldmann, who held “seance-like gatherings,” formulating detailed and futile plans for escape.

The spasm of generosity in which those soon to be transported to a new and unknown fate are given meagre gifts, a cigarette stub and a chunk of cabbage, by those who are left behind for the time being: “In the minds of those staying behind, this imperative throbs away: We’ve got to give, to give something.”

If this suggests residual humanity, there are in this coruscating bolt of truth none of the implausibilities and glib moral take-homes that have plagued and devalued Holocaust fictions, from Life Is Beautiful to The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas.

Debreczeni’s book makes spectacularly clear the difficult but necessary double demand of the Holocaust and its memorialization: what we might call the demands of the universal and the particular, or the general and the specific. To do its memory any kind of justice must mean to proclaim never again, for anyone: to decry and oppose all acts of mass violence. But the urgency of deriving this general imperative must not mean rushing too quickly past the particulars of what the Nazis and their enablers perpetrated; past its industrialized scale and mechanisms, its bureaucratized intricacies, its sheer massiveness and the massiveness of each life flayed, reduced, and destroyed.

Only through the difficult act of keeping both the general imperative and the specific example in mind at once can we hope to answer Debreczeni’s anguished call into the void on his first night at Dornhau: “Come here, you visionaries who create with pen, chalk, stone, or paintbrush; all of you who’ve ever sought to conjure up the grimace of suffering and death; prophets of the danse macabre, engravers of terror, scribes of hells — come here!”

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

The term “pirates” as used in Asia was a European term that, as scholar of Asian pirate history Robert J. Antony has observed, became globalized during the European colonial era. Indeed, European colonial administrators often contemptuously dismissed entire Asian peoples or polities as “pirates,” a term that in practice meant raiders not sanctioned by any European state. For example, an image of the American punitive action against the indigenous people in 1867 was styled in Harper’s Weekly as “Attack of United States Marines and Sailors on the pirates of the island of Formosa, East Indies.” The status of such raiders in

As much as I’m a mountain person, I have to admit that the ocean has a singular power to clear my head. The rhythmic push and pull of the waves is profoundly restorative. I’ve found that fixing my gaze on the horizon quickly shifts my mental gearbox into neutral. I’m not alone in savoring this kind of natural therapy, of course. Several locations along Taiwan’s coast — Shalun Beach (沙崙海水浴場) near Tamsui and Cisingtan (七星潭) in Hualien are two of the most famous — regularly draw crowds of sightseers. If you want to contemplate the vastness of the ocean in true