In 1519, the German scholar Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa intervened to secure the release of a poor woman accused of witchcraft by a zealous inquisitor, who claimed that such women conceive children by demons.

“Is this how theology is done nowadays, using nonsense of this sort to put innocent little women to the rack?” Agrippa demanded.

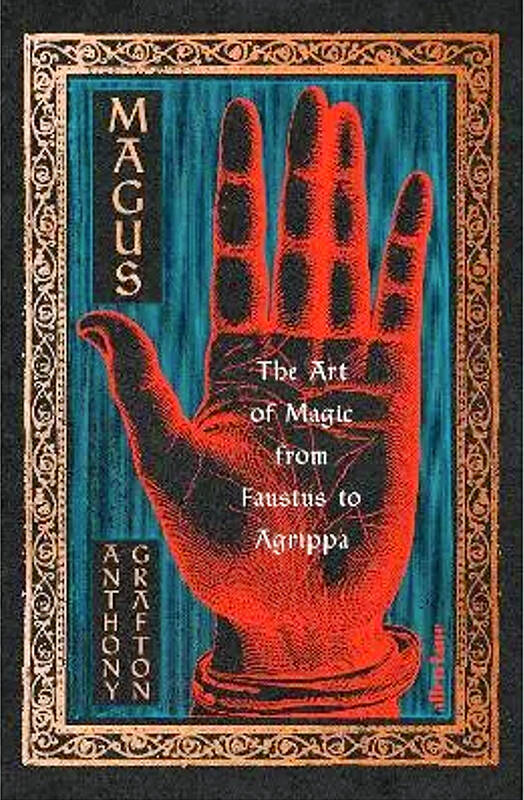

The incident is recounted in Magus: The Art of Magic from Faustus to Agrippa, Anthony Grafton’s dense and fascinating study of the evolution of magic through the 15th and 16th centuries, and it illustrates some of the contradictions and divisions that made the understanding and pursuit of hidden knowledge so fraught at the time.

Grafton, a professor of history and the humanities at Princeton University, shows that “magic” was a vast umbrella term encompassing everything from love philtres and homespun remedies involving the bones of toads, to proto-scientific disciplines such as cryptography, optics and engineering. When practiced by women and unlettered people (not to mention those of other faiths), it usually led to accusations of witchcraft, but articulated and published by learned men, it resulted in books that became the international bestsellers of their day.

Not that the learned men wholly escaped censure by the religious and civic authorities for their determination to test the boundaries of human knowledge. Agrippa — whom Grafton calls “the greatest magus of the 16th century” — had to fight to get his magisterial three-volume work On Occult Philosophy past the censors by appealing directly to the bishop of Cologne; although the book immediately went through three printings, it was widely banned and, according to Grafton, effectively ended its author’s writing career.

The Jesuit demonologist Martin Del Rio published a collection of tabloid-style anecdotes accusing Agrippa of practicing diabolic magic: “When he and Faustus travelled together, Del Rio claimed, they paid their bills in inns with coins that seemed genuine but turned into bits of horn after a few days.”

It examines the often uneasy, sometimes beneficial, three-way relationship between religion, magic and science

Faustus is, of course, the most infamous of the colorful characters who populate the pages of Magus — “a perfect star for this period show” — and Grafton attempts to separate the scant historical fact from the tangle of legends that surrounded him even in his lifetime.

Grafton tentatively identifies the original Faustus as Georg of Helmstadt, a schoolteacher dismissed from his post in 1507 on charges of sodomy, who reinvented himself as an itinerant magician and traveled around the Holy Roman empire building a reputation for supernatural powers so formidable that, on being expelled from the city of Ingolstadt, the council made him swear an oath not to take revenge.

But even at the time, opinion on the nature of Faustus’s powers was contentious. Some influential figures, including Martin Luther and his followers, attributed them to a diabolic pact (Luther claimed that Faustus called the devil “his brother-in-law”), while others, notably the Benedictine abbot Johannes Trithemius, who gets his own chapter later in the book, considered him a fraud — “a vagabond, a babbler and a rogue, who deserves to be thrashed.”

Through the principal magi of the high Renaissance, Grafton examines the often uneasy, sometimes beneficial, three-way relationship that existed between religion, magic and science. From outre self-publicists like Faustus to respected scholars such as the Florentine friends Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, who attempted to synthesize occult knowledge (including Jewish and Islamic learning) with Christian doctrine, he traces the expression of a desire for a comprehensive understanding of the cosmos and man’s place within it, as well as the drive to control the natural world, that paved the way for the evolution of scientific method.

“The magus,” he writes, “is a less respectable figure than the artist or the scientist… but he belongs in a dark corner of the same rich tapestry.”

Grafton’s inspiration for the book came from the work of the 20th-century scholar Frances Yates, who opened up the field of Renaissance occult philosophy, and while Magus is peppered with entertaining anecdotes, it is nonetheless a scholarly study that will most likely be more accessible to readers who already have some familiarity with the ideas of the period. It also feels as if it ends rather abruptly after the chapter on Agrippa; I would have been interested to read even a brief conclusion outlining the influence of the magus on later figures in the history of science. But these are quibbles; Magus is rich in detail and generously illustrated with examples of diagrams, ciphers and images.

In an age when the pace of new technological developments and our ability to harness forces beyond the human are giving rise to ethical questions and fears about the limits of knowledge, a long view of our relationship with magic could not be more timely. Because the concept of magic, Grafton writes, “played a crucial role in the rise of something larger than magic: a vision of humans as able to act upon and shape the natural world.”

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the