In October 1954, a clerk working at the British embassy in Moscow, John Vassall, was invited to a party. Vassall got into a taxi with a “dark-haired stranger” and found himself in the Hotel Berlin. There, he had dinner with a group of Russian men in a private dining room. Soon, he was naked and lying on a divan. Two men raped him. Another took photographs. At 3:30am they brought him home in a taxi.

The episode — organized by the KGB’s second chief directorate — was a classic honeytrap. A few months later Vassall had a consensual sexual encounter with a uniformed Russian military officer. KGB operatives burst in on them. They showed Vassall photos taken previously and laid out his options. He could spy for Moscow, or be ruined and exposed.

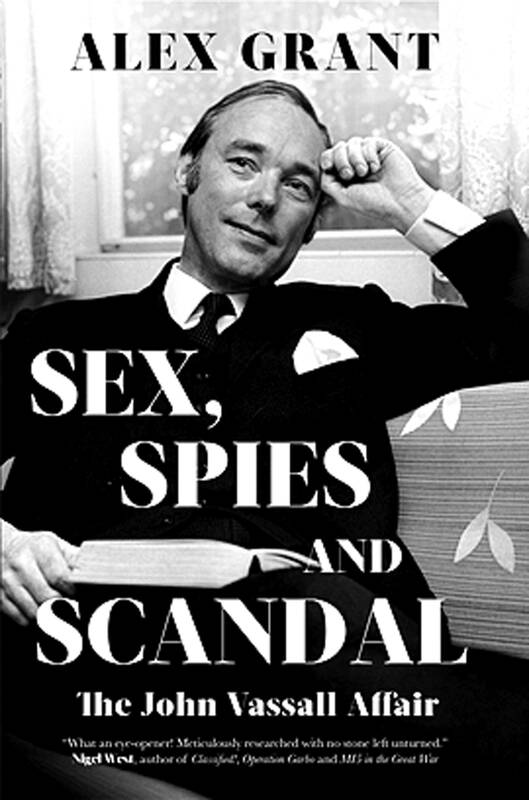

Alex Grant’s biography of Vassall, Sex, Spies and Scandal, is a sympathetic telling of this largely forgotten cold war episode. Vassall might have confessed all. Instead, he spent six years handing over British state secrets to his Soviet handlers, first in Moscow where he worked in the office of the naval attache, and then in London. He turned out to be a resourceful agent, snapping documents with a Minox camera.

There were meetings in the Russian capital with dark figures in long coats. Sometimes Vassall would sit in the back of a car with an intelligence officer, and pass on gossip about visiting Labour delegations, including a conversation he had with Barbara Castle. There were strolls in the country. Nikolai Rodin, the head of the KGB’s London residency, flattered Vassall and told him his clandestine work helped the cause of peace.

‘TRAGIC VICTIM’

In 1957, and back in Britain, Vassall got a clerical job in the naval intelligence division, followed by the office of the civil lord to the admiralty. He passed on highly classified details of British and NATO naval policy and weapons development. Rodin told Vassall to meet him in suburban stations — Alperton and Harrow — and gave him cash. This allowed Vassall to rent a luxury flat in Dolphin Square and to fill it with antiques.

In Grant’s view, Vassall was more “tragic victim” than hard-nosed perpetrator. As a gay man, he faced prosecution for criminal activity in the USSR and England, where homosexuality was illegal until 1967. In a memoir Vassall said he might have been “more courageous” if attitudes had been different. Instead, homophobia was rampant in politics, the security agencies and the press.

For the KGB, Vassall was a perfect blackmail target. He was naive, vain, a bit smarmy according to contemporaries and obsessed with social status: a low-level employee with access to high-level stuff. Before his arrest in 1962, his superiors described him as plodding. But, they added, he was impeccably dressed and with pleasant manners. At times he seemed lonely.

Grant argues that Vassall’s story is an untold part of Britain’s LGBT history. At the time it was an enormous scandal, which embarrassed the Macmillan government and led to a witch-hunt across Whitehall and Westminster for other “gay traitors.” Several of Vassall’s male friends were sacked. The MP Tam Galbraith — wrongly suspected of having a relationship with Vassall — was forced out of the admiralty and parliament.

PROFUMO AFFAIR

Soon, though, the Profumo affair — involving the secretary of state for war, John Profumo — knocked Vassall off the front pages. Profumo slept with a 19-year-old model, Christine Keeler, while she may have been involved with a Soviet naval attache. Screenwriters and historians have given attention to Profumo, because his downfall features “attractive young women” rather than men, Grant suggests.

There is another version: that Vassall’s case is less interesting than that of better known and politically driven traitors. Special Branch detained him in the Mall after a tip-off from a KGB defector. In custody, Vassall promptly admitted he had been stealing secrets. He told police that the bookcase in the corner of his bedroom contained a hidden compartment used to store camera films.

Sentenced to 18 years in jail, Vassall found himself in Wormwood Scrubs. Also there was George Blake, the MI6 officer turned double agent. The two inmates attended an English literature class. Otherwise they had little in common. Blake was a committed communist who spied for ideological reasons. He escaped over a wall and made his way to Moscow, where he got to know several of the Cambridge Five, a group of upper-class co-believers.

Vassall, by contrast, was a model prisoner. He talked at length to MI5 about Soviet tradecraft. (The KGB used the tube, he revealed.) Vassall had no desire to return to Moscow and was not much interested in international events — Suez, the Cuban missile crisis, the Hungarian uprising. In jail, he preferred to write letters to upper-class acquaintances and to lady admirers. After his release in 1972 Vassall’s life was unremarkable.

ANTI-GAY PARANOIA

Grant’s biography is good on the anti-gay paranoia that gripped British institutions in the 1950s and 1960s, wrecking lives and causing misery. He is less interested in the Soviet shadow world and the mentality of its practitioners. Was Rodin, Vassall’s handler, a cynic or a Marxist zealot? How much damage did Vassall do? The KGB’s archive is unavailable, and we still don’t know what exactly Vassall swiped.

Seventy years on, Vladimir Putin’s security services use the same voyeuristic playbook. In 2013 a budding American politician, Donald Trump, stayed in Moscow’s Ritz-Carlton hotel. Trump denies he cavorted there with prostitutes. A bipartisan Senate report found that the FSB — the KGB successor agency — installed hidden cameras in guest bedrooms. An FSB officer based at the hotel reviewed footage.

Trump’s fawning remarks about Putin may be the product of dictator envy. Or they could have something to do with kompromat. Either way, Moscow continues to target the reckless and unwary, using methods honed during the Vassall era and the early cold war. Then as now, the Kremlin sees itself in a constant battle against the west, in Ukraine and across the globe. Everyone has a flaw, if you look hard enough; any weakness can be exploited.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.