Understanding the threat posed by climate change is one thing. Being able to minimize the detrimental impact of your decisions is another.

When shopping for groceries, not everyone has the time or knowledge to identify low-carbon options. And for the majority of products, the information available to the public is incomplete. This is why several countries, including Taiwan, have recognized the importance of carbon footprint labeling.

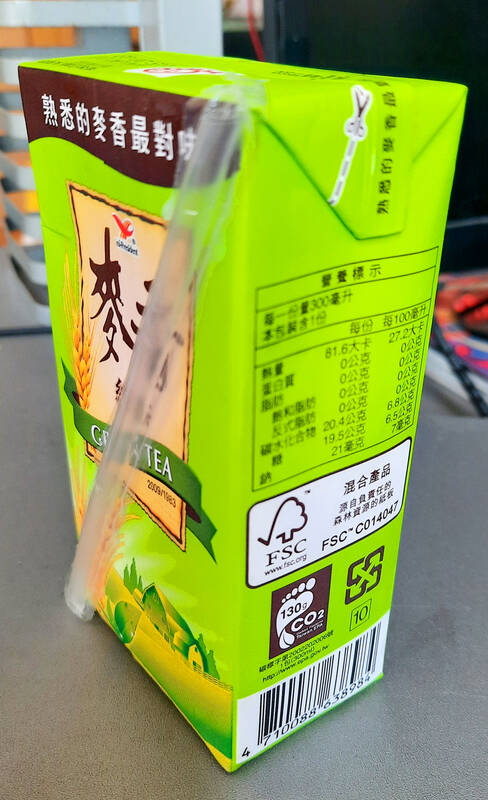

Taiwan’s Carbon Footprint Information Platform (CFIP) exists to help the public understand different carbon-footprint labels, the Ministry of the Environment explained in a Dec. 26 email to the Taipei Times. The majority of labels authorized so far state the product’s total carbon footprint. To earn a downward-pointing arrow, an enterprise must prove that carbon emissions associated with the product have been reduced by at least 3 percent within five years.

Photo: Wang Jung-hsiang, Taipei Times

While there’s no specific subsidy for enterprises that pursue or obtain a label, the environment ministry said that, by sharing information about carbon emission factors (such as electricity use or burning diesel for road transportation), the platform lowers the cost of calculating the carbon footprint for individual products.

In the same message, the ministry said, “our carbon footprint labeling scheme remains a voluntary scheme, like other countries.”

This isn’t entirely accurate: Since Jan. 1 last year, major businesses in France have been required to disclose to the consumer at the time of purchase, through a physical label or the brand’s Web site, the environmental and climate-impact characteristics of a variety of waste-generating products, including textiles and footwear.

Photo: Steven Crook

According to the CFIP’s English-language Web site, Taiwan was the 11th country in the world to develop a carbon footprint labeling protocol. This claim doesn’t appear on the platform’s more detailed Chinese-language Web site (cfp-calculate.tw), which also points out that that carbon footprint assessments help manufacturers to understand where in a product’s life-cycle greenhouse gases (GHGs) are emitted, after which they can work to reduce those emissions by reviewing material inputs, reducing packaging and/or making transportation more efficient.

Supply chains that are greener, “usually also achieve cost reductions,” the CFIP Web site says. For consumers, the certification system makes it easier to “prioritize purchasing products with carbon labels, to support manufacturers who divulge carbon footprints.”

USELESS LABELS?

Photo: Steven Crook

The world’s first carbon labels were launched in the UK in 2007, followed by Switzerland in 2008 and South Korea in 2009. Taiwan’s CFIP started accepting applications in 2010.

The US has three competing systems, none of which are endorsed by the federal government. There’s no internationally-unified standard for carbon footprint labels.

In the early days of carbon footprint labeling in Taiwan, the CFIP Web site concedes, so few products had obtained certification that it was impossible for consumers to make like-for-like comparisons. Nowadays, shoppers can at least know the relative climate impact of bottled waters and pineapple cakes.

A 500ml bottle of Yes-brand sparkling water has a greater carbon footprint (340g of CO2e) than a 1460ml bottle of Twist-brand non-sparkling drinking water (260g).

In an undertaking posted alongside the product profile on the CFIP Web site, the manufacturer of the former says it’ll convert their plant’s boiler system to run on natural gas; combined with other measures, that will help achieve a reduction in GHG emissions of approximately 2.2 percent.

Twist’s maker expects to cut its emissions by 3 percent in three years, having already achieved a significant reduction by redesigning its bottles. The 1460ml container now weighs just 23 g — down from 34 g — lowering emissions not only during the manufacturing stage, but also when trucking bottles to points of sale. Obtaining raw materials accounts for 59.82 percent of the product’s total footprint; manufacturing is 2.84 percent; distribution and sales is a whopping 34.46 percent; while disposal accounts for another 2.88 percent.

But it goes without saying that, in a country where drinking-water fountains are easy to find, anyone who’s seriously concerned about climate change and plastics pollution (see “Reducing Taiwan’s virgin plastics” in the May 25, 2022 Taipei Times) shouldn’t be buying bottled water at all.

Pineapple cake is thought of as a quintessential local product, yet Kuo Yuan Ye’s (郭元益) Taiwan Golden Prize Pineapple and Yolk Shortcake contains a surprising number of imported inputs. While the pineapple, winter melon and egg yolk are sourced from within Taiwan, the pastry is made using imported flour, Dutch cream, Danish cheese powder and New Zealand milk powder. This goes some way to explaining why an edible that weighs less than 50g is responsible for 260g of CO2e.

Jiu Zhen Nan (舊振南), a Kaohsiung-based maker of baked goods in business since 1890, has assessed the climate impact of its pineapple cakes at 240g CO2e per 35g treat. The company’s CFIP’s entry says that, by installing more efficient machinery and optimizing the manufacturing process, it anticipates a further carbon-footprint reduction of 2 percent.

According to Kimber Kuo (郭念鑫), director of the company’s Branding and Marketing Department, Jiu Zhen Nan joined the CFIP because it recognizes its environmental protection and carbon-reduction obligations. Kuo says the company hopes that, by displaying the carbon footprint label, consumers will understand Jiu Zhen Nan’s commitment to environmental principles at every point in the manufacturing and distribution process.

There’s also a business calculation. Ahead of holiday seasons, Kuo says, the companies which buy in bulk from Jiu Zhen Nan for public-relations gifting insist that each box of pineapple cakes carries a carbon footprint certification mark to reflect their own values.

Jiu Zhen Nan’s GHG calculations were double-checked by SGS Taiwan, one of five companies authorized by the environment ministry to provide carbon-footprint verification services. Kuo declines to reveal how much the entire assessment and certification process costs, saying only that it wasn’t easy.

DO CONSUMERS CARE?

According to the results of a survey conducted by IPSOS and released on Feb. 28 last year, 76 percent of Europeans would like the carbon footprint of each food item to be visible on its label. Moreover, 58 percent of Europeans say they consider the climate impact important when buying food and beverages, and 51 percent express a willingness to pay more for food produced without the use of any fossil fuels.

However, it isn’t clear if consumers understand such labels. In a 2021 paper in the Journal of Cleaner Production, researchers at the University of Reading’s School of Agriculture, Policy and Development noted that people who express concern about the environment and those who frequently buy foods labeled as eco-friendly “are willing to pay more for carbon-footprint labeled foods.” They went on to say that “consumers still have poor knowledge of carbon measurements,” and carbon-footprint information seems to have less impact on purchasing decisions than other organic or Fair Trade labeling.

Now in its second decade, Taiwan’s CFIP covers a mere 530 items, up from 394 in 2016. Among them are: beverages, condiments and processed foods; reusable chopsticks; shower gels and shampoos; tissue paper; and several credit cards. Tainan City Government’s Bureau of Transportation has assessed the carbon footprint of its electric buses as 90g CO2e/per person-per kilometer.

But for people planning to buy a smartphone, a car or a motorcycle, a refrigerator or a washing machine, shoes or clothes, the CFIP is no help.

There’s local evidence to suggest that, if the carbon labeling scheme was heavily promoted and more products were included, it’d have a meaningful impact.

Working with a handful of convenience stores in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), scholars from National Taiwan University of Science and Technology and National Taipei University encouraged 1,900 residents to open personal accounts that tracked purchases of 20 “carbon-negative” products. (Making those products generated GHGs, but the emissions were more than offset by purchased carbon credits.)

In a paper published by Sustainability in July last year, the scholars described their goal as encouraging individuals to take personal responsibility for their carbon footprint and “make good use of consumer sovereignty and wise consumption power.” Analysis of sales data shows that the scheme is “economically feasible” and could be scaled up, they concluded. And because carbon labeling is fundamental to such efforts, the promotion of such labels “is needed and is recommended to ensure a successful carbon-neutral living transition.”

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

Climate change, political headwinds and diverging market dynamics around the world have pushed coffee prices to fresh records, jacking up the cost of your everyday brew or a barista’s signature macchiato. While the current hot streak may calm down in the coming months, experts and industry insiders expect volatility will remain the watchword, giving little visibility for producers — two-thirds of whom farm parcels of less than one hectare. METEORIC RISE The price of arabica beans listed in New York surged by 90 percent last year, smashing on Dec. 10 a record dating from 1977 — US$3.48 per pound. Robusta prices have

The resignation of Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) co-founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) as party chair on Jan. 1 has led to an interesting battle between two leading party figures, Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) and Tsai Pi-ru (蔡壁如). For years the party has been a one-man show, but with Ko being held incommunicado while on trial for corruption, the new chair’s leadership could be make or break for the young party. Not only are the two very different in style, their backgrounds are very different. Tsai is a co-founder of the TPP and has been with Ko from the very beginning. Huang has

A few years ago, getting a visa to visit China was a “ball ache,” says Kate Murray. The Australian was going for a four-day trade show, but the visa required a formal invitation from the organizers and what felt like “a thousand forms.” “They wanted so many details about your life and personal life,” she tells the Guardian. “The paperwork was bonkers.” But were she to go back again now, Murray could just jump on the plane. Australians are among citizens of almost 40 countries for which China now waives visas for business, tourism or family visits for up to four weeks. It’s

A dozen excited 10-year-olds are bouncing in their chairs. The small classroom’s walls are lined with racks of wetsuits and water equipment, and decorated with posters of turtles. But the students’ eyes are trained on their teacher, Tseng Ching-ming, describing the currents and sea conditions at nearby Banana Bay, where they’ll soon be going. “Today you have one mission: to take off your equipment and float in the water,” he says. Some of the kids grin, nervously. They don’t know it, but the students from Kenting-Eluan elementary school on Taiwan’s southernmost point, are rare among their peers and predecessors. Despite most of