Deep in the mountains of Hsinchu County, a few dozen residents of Smangus are holding their daily morning meeting in a weatherboard hut, overlooking the towering peaks nearby.

The remote Indigenous village, home to about 200 people from the Atayal community, is preparing for Saturday’s presidential election. They take it very seriously, running their own polling station since 2008, and discussing candidates with all the residents.

“We normally don’t talk about politics [at the meeting] but the presidential election is a big deal,” says Lahuy Icyeh, a community leader. “The village elders encourage the tribe to choose who is best for Taiwan.”

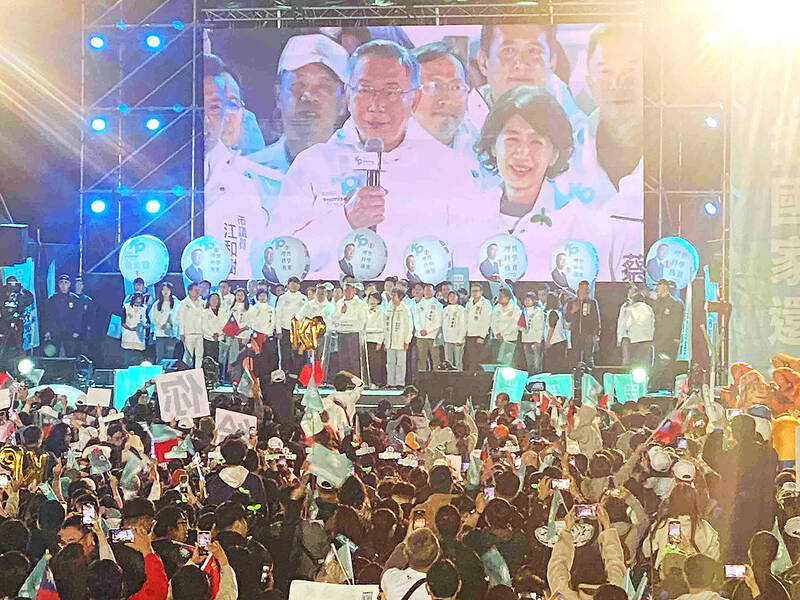

Photo: Lee Jung-ping, Taipei Times

The vote will be Taiwan’s eighth direct presidential election since martial law ended in the late 1980s. The current president, Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), must step down due to term limits, and her current deputy, William Lai (賴清德), is running to keep the Democratic Progressive party (DPP) in power. He’s up against Hou You-yi (侯友宜) of the national opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), which ruled during the decades of authoritarianism, and the Taiwan People’s party (TPP), led by founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲).

DOMESTIC ISSUES

The campaign has been dominated by the Chinese Communist party’s threat to annex Taiwan, but surveys have shown it is economic issues that are the main concern of voters, including low wages, housing affordability, energy security and inflation. In 2022, wages had the steepest yearly decline in 10 years, while housing in some Taiwanese cities ranks among the world’s most expensive relative to income.

Photo: Wang Shu-hsiu, Taipei Times

Inflation was lower than many other countries last year — 2.48 percent — but a series of extreme price rises on individual products such as eggs worsened perception of the cost of living.. There are also Care for children and the elderly, corruption, judicial reform, education and rights for minorities are also immediate concerns.

All three presidential candidates have made pledges addressing most big-ticket items but many of them are quite similar. Dafydd Fell, director of the Centre of Taiwan Studies at Soas University of London, says this has neutralized most debates except on the contentious future of Taiwan’s nuclear power plants. Publication of polling — which could show any potential impact of these pledges — is banned in the 10-day blackout period prior to the vote.

The Smangus community has clear asks: better assistance for elderly care, road improvements and land rights and transitional justice for Indigenous tribes. But the village, which operates a kibbutz-style economy, including shared land and housing, and a flat-salary jobshare system, is protected from some of the economic issues.

Photo: Huang Hsu-lei, Taipei Times

For them, the presidential election is about big picture themes, says Yarah Pihu, Smangus’s Presbyterian minister and a community leader.

“We want a president with an international perspective and a sense of Taiwanese identity.”

Masay Sulung a Smangus community leader, said: “I expect 90 percent of Smangus to vote for [William] Lai Ching-te. We have high expectations for Lai, he has a clear vision for the country.”

Photo courtesy of the office of Tseng Wen-Hsueh

At a DPP rally in Taipei, 20-year-old university students surnamed Huang and Chen say they support the DPP’s stance on gender issues, Taiwanese identity and care for the elderly. But there are signs that young people — who make up about 16 percent of the voting public — are moving away from the DPP, which is now seen by them as the establishment.

At a KMT rally, a 34-year-old man surnamed Liu says he’s switching from the DPP because he thinks governments should change frequently. In Guanxi township, Hsinchu County, one woman surnamed Lee, feels the same, but she doesn’t like Hou or Ko, so she’s just not going to vote.

CORRUPTION

Corruption is another major issue for most Taiwanese voters. Fell says political corruption is often the “most stressed issue in Taiwanese elections and has been the most influential issue in a number of local and national elections.”

“After eight years in office, you would expect the DPP to be threatened by this issue, and the KMT has made a number of accusations. But it is not entirely clear which side owns this issue,” he added.

Candidates have flung a dizzying range of accusations at each other, from plagiarism to illegal housing structures, dodgy income streams and other forms of corruption. Past local elections have seen allegations of vote-buying, bribery, voter intimidation and political links with organized crime.

“Taiwan’s local politics has been long dominated by ‘electoral machines’ — a system of voter mobilization through networks of patronage and local political factions — ever since the authoritarian era,” says Kevin Luo, assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Minnesota. “The entrenchment of the KMT party machine in Miaoli is a good example.”

According to the Taiwan Anti-Corruption and Whistleblower Protection Association, 11.6 percent of 1,677 city councilor candidates in 2022 had criminal records — more than 20 percent of them in Miaoli County, New Bloom Magazine reported.

On a Friday night, independent candidate Tseng Wen-Hsueh (曾玟學) is rallying a crowd of people at a temple in Miaoli County, on a platform of anti-corruption and political change. Party loyalty runs deep here among a diverse mix of ethnic groups and a high proportion of state-run employers in its large natural resources sector. In 72 years, Miaoli has never voted against the KMT, regardless of national trends. A popular joke refers to it as “Miaoli Nation.”

“Miaoli’s closed political environment allows those in power to do whatever they want,” Tseng tells the Observer. Most people struggle to imagine change after so long without it, he says. “So most of the people tend to continue to choose KMT for the sake of stability in their own lives. [But] if someone wins for the first time, the public will have confidence when they vote, this is the most important thing. The public will understand that this vote in hand can really bring about changes.”

Once known as Taiwan’s most remote village, Smangus only got electricity in 1980, and a road to neighboring villages in 1995. That road — a trail of switchback turns and fuel-sucking inclines, punctuated by the remnants of frequent landslides — is now busy with campaign trucks and candidate advertising.

But in Smangus the vote is largely decided. Since at least 2008, the village has voted for the DPP in almost direct inverse proportions to the pro-KMT region it sits in. But the main thing is that they will vote.

“We enjoyed democracy later than other places,” says Icyeh. “ It’s important to choose someone who can protect and lead Taiwan and appreciate our hard-won democracy.”

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had