Whether it is the waft of clove-studded oranges or the crisp fragrance of a fir tree, the festive season is filled with aromas that conjure Christmases past. Now researchers say our sense of smell, and its connection to our memory, could be used to help fight dementia.

Our senses can worsen as a result of disease and old age. But while impairment to hearing or vision is quickly apparent, a decline in our sense of smell can be insidious, with months or even years passing before it becomes obvious.

“Although it can have other causes, losing your sense of smell can be an early sign of dementia,” said Leah Mursaleen, the head of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, adding it was a potential indicator of damage in the olfactory region of the brain — that is, the part of the brain responsible for smell.

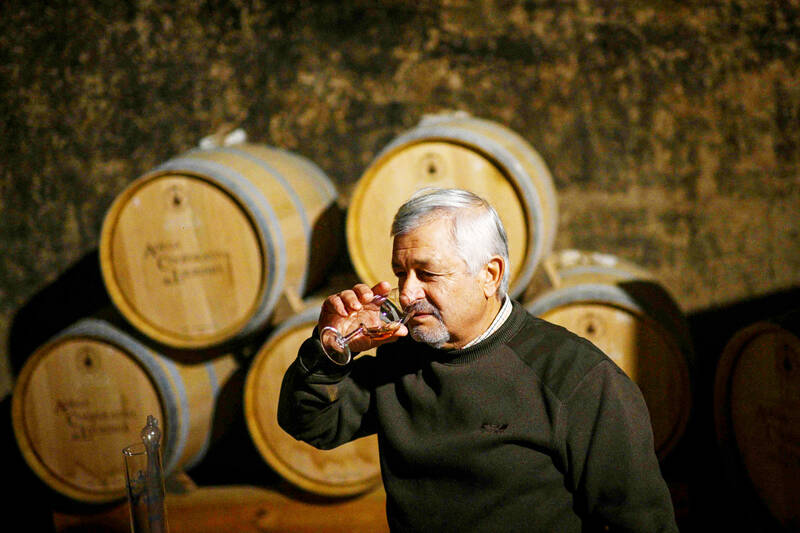

Photo: AFP

That has led to researchers examining whether loss of smell could be used to diagnose conditions such as Alzheimer’s long before symptoms such as memory loss set in — an approach, experts say, that could allow patients access to drugs such as lecanemab early in the course of the disease, when they work best to slow cognitive decline.

But just as research has suggested the use of hearing aids could reduce the risk of developing dementia, questions are being asked about whether bolstering our sense of smell could do the same. Could a declining sense of smell be a risk factor for cognitive decline, not just a symptom?

“Olfaction is intimately involved in many brain processes, and especially the emotional processing of stimuli,” said Thomas Hummel, of Technische Universitat Dresden. Indeed, smells, memories and emotions are often tightly bound, with research revealing recollections triggered by scent tend to be rooted in our childhood.

Photo: AFP

“If olfactory function fails, stimuli lose salience, which may affect general cognitive functions,” said Hummel.

Neurons involved in the olfactory system are also involved in other systems in the brain. Indeed, as Hummel and others note, some areas of the brain play a key role in cognitive and olfactory processes. As a result, if the sense of smell becomes dysfunctional, cognitive processing might also be affected.

A number of studies have found that exposure to certain odors can either boost or hinder cognition, while work by Hummel and colleagues has suggested smell training in older people can improve their verbal function and subjective wellbeing.

More pertinent still, a small study published last year by researchers in Korea, revealed that intensive smell training led to improvements in depression, attention, memory and language functions in 34 patients with dementia compared with 31 participants with dementia who did not retrieve such training.

“We’ve already seen some early studies suggesting that ‘training’ our sense of smell, through repeated exposure to strong-smelling substances, could have benefits in improving cognitive performance in certain tasks,” said Mursaleen.

“However, much more research is needed to understand whether things like olfactory training could help prevent or slow down the onset and progression of mild cognitive impairment and dementia.”

Among other problems, intensive scent training takes time and effort. In an attempt to solve this problem, Michael Leon, professor emeritus at the University of California, Irvine, and his team have come up with a device called “Memory Air that emits 40 different smells twice a night, while people are sleeping — an approach Leon says allows “universal compliance.”

The hope is that exposing people to more smells, even when they are asleep, could strengthen their olfactory abilities.

The team is about to start a large trial with the gadget among older adults without dementia, building on a smaller study that suggested the approach could improve memory performance in such participants.

“We will then start a large trial with Alzheimer’s patients using that device,” said Leon.

In another small study, Alex Bahar-Fuchs, a clinical neuropsychologist at Deakin University, Australia, is looking at whether training cognitively healthy older adults to distinguish smells using a scent-matching memory game can help improve wider aspects of memory and cognition, compared with using a similar game based on matching pictures. The approach, he said, goes further than passive exposure to odors by setting cognitive tasks for participants.

“We believe that the neuroplastic properties of the olfactory centers in the brain might make it more likely that improved performance on olfactory memory will generalize, or transfer, to memory functions more broadly,” he said.

Meanwhile, Victoria Tischler, at the University of Surrey, is working to learn more about how our olfactory function changes as we age normally.

As part of their work, the team hopes to produce olfactory training kits suitable for healthy older people, those with mild cognitive impairment, and those living with dementia in care homes.

Tischler said it was important to cherish our most enigmatic sense.

“I would advise the public to look after their sense of smell, much like they look after other aspects of their sensory health” such as their eyesight, she said.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the