Bradley Cooper’s Maestro, a high-wire act of a biopic, leaps constantly between on stage and off, flying through Leonard Bernstein’s very public life as a conductor while diving into his more private marriage to Felicia Montealegre. How each side of Bernstein’s existence interacts with the other is the tension and harmony of Maestro. Which is authentic? Which a performance?

Resolving those dichotomies is, thankfully, not the aim of Cooper’s admirably ambitious if performative drama about the musical conscience of 20th century America. Bernstein’s polymorphous life was spread between his family life and a string of male lovers, just as it was between conducting and the solitary toil of composing. Maestro resists neat conclusions about any facet of an expansively contradictory life.

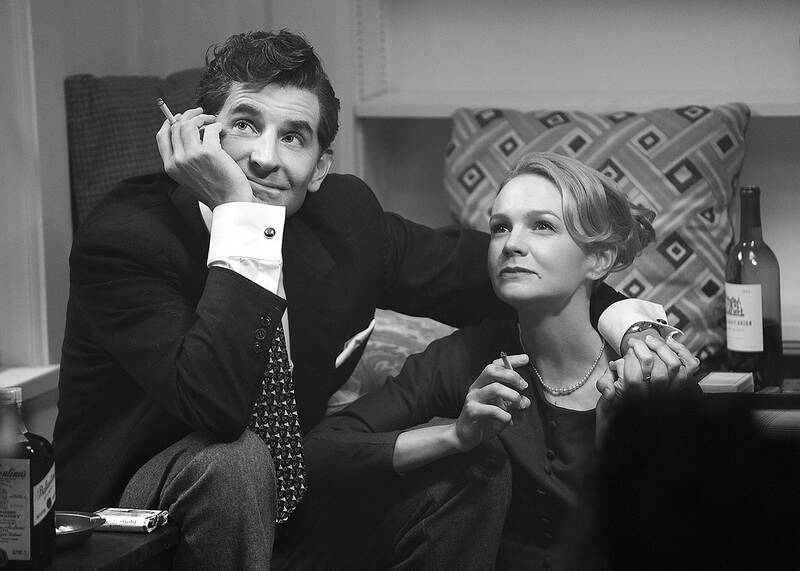

“If you carry around both personalities, I suppose that means you become a schizophrenic and that’s the end of it,” Bernstein (Cooper) says with a laugh in a TV interview alongside Montealegre (Carey Mulligan).

Photo: AP

Maestro, which streams next month on Netflix, isn’t a cradle-to-the-grave biopic, though it doesn’t avoid some of the genre’s standard pitfalls, either. It’s largely set around the beginning and end of his relationship with Montealegre, an actor he first meets at a party.

“Hello, I’m Lenny,” he says, grinning from the piano bench.

It’s a framework with some benefits — no matter what the title says, this is Mulligan’s movie — that also omits much of Bernstein’s most lasting accomplishments. There is little here of music making, generally, and virtually none of West Side Story, Candide, On the Waterfront or all those influential TV broadcasts. Fans such as Lydia Tar may not approve.

Photo: AP

But Maestro begins, thrillingly, in a black-and-white blur. Characters exit scenes like they’re falling through trap doors, a surreal swirl propelled by the verve of Bernstein’s music. In the first scene, a 25-year-old Bernstein is woken with a call notifying him to substitute for Bruno Walter in conducting the New York Philharmonic that night. Enthralled, he pulls open the blinds, slaps, in rhythm, the bare bottom of the man sharing his bed and runs down stairs that magically lead right into Carnegie Hall.

It won’t be the last time that Maestro draws a straight line between lovemaking and music.

“If nothing sings in you, then you can’t make music,” Montealegre will later tell him. Music, no doubt, swells most in the Bernstein of Maestro when he’s liberated to be himself.

Photo: AP

On the night of their first date, Bernstein and Montealegre end up, fittingly, on a stage running lines, with one floor lamp casting them in shadow.

“Even though you’re the king, you’re quite taken with me,” she says, explaining his characterization.

The fiction is quickly borne out, albeit with a foreboding sense of marital trouble. Another headlong sprint between scenes ends with the two rushing onto the stage of Fancy Free, the Jerome Robbins ballet that will lead to On the Town. Bernstein, himself, joins the hip-swinging sailors.

Maestro is, for this roughly first black-and-white hour, wonderfully brisk and free of normal biopic constraints. It’s like a dream of 1950s New York modernism. Dialogue moves at an urbane clip. The photography, by Matthew Libatique, dips confidently between intimate exchanges and wide-shot vistas of the Berkshires of Tanglewood or of Central Park. (This is, most definitely, a great Central Park movie, full of romance and encounters along its pathways.)

When Maestro shifts forward and into color, it loses its brio. The film, which Cooper wrote with Josh Singer, skips over the central decades of Bernstein’s accomplishments, taking up residence instead in the early 1970s.

By then, Bernstein and Montealegre are married with three children (the oldest, Jamie, is played by Maya Hawke) and a house in Connecticut. But even though Montealegre entered into the marriage without wool over her eyes (“I know exactly who you are,” she tells him, early on), all is now discord. Bernstein’s dalliances, she tells him, have gotten sloppy. In a Thanksgiving Day argument in their Manhattan apartment overlooking the park, she seethes: “If you’re not careful, you’re going to die a lonely queen.”

Right about then, an inflated Snoopy floats past the window, like an eclipse.

In scene after scene like this, Maestro is staged exquisitely. But even as the film moves from its nervy first hour to its melodramatic set pieces, artifice steadily grips Maestro. Cooper’s Bernstein has come under criticism for the prosthetic nose, but it’s other affectations in his performance that smother. It’s a sincere performance, thoughtful and dedicated, but it’s also mannered and showy, drowning in turtlenecks, cigarettes and accents.

But Cooper, a sensitive director, was also wise enough to follow Mulligan’s increasingly moving performance. (She gets top billing, too.) The film’s slide into family dynamics comes at the expense of Bernstein’s larger story, but it yields a beautiful platform for Mulligan to capture a woman too infatuated by her husband to abandon him, but too clear-eyed not to be devastated.

“It’s my own arrogance to think I could survive on what he could give,” she says.

It’s a powerfully piercing moment, followed by an extended, passionate recreation of Bernstein in 1976 conducting Mahler’s Second Symphony. There, gyrating at the podium before an orchestra, the film tells us, may be where Bernstein truly gives all of himself.

Some of America’s top filmmakers have long been tempted to tackle a film on Bernstein, among them Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg (both credited producers here). But Cooper’s film never finds its balance. If Bernstein’s sexuality must be the prism through which we view him, why do his male lovers (Matt Bomer makes a brief impression) pass by so fleetingly? Maestro is a fine portrait of a complicated marriage. But for a man who contained symphonies, that leaves a lot of notes unplayed.

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

This was not supposed to be an election year. The local media is billing it as the “2025 great recall era” (2025大罷免時代) or the “2025 great recall wave” (2025大罷免潮), with many now just shortening it to “great recall.” As of this writing the number of campaigns that have submitted the requisite one percent of eligible voters signatures in legislative districts is 51 — 35 targeting Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus lawmakers and 16 targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers. The pan-green side has more as they started earlier. Many recall campaigns are billing themselves as “Winter Bluebirds” after the “Bluebird Action”

Feb 24 to March 2 It’s said that the entire nation came to a standstill every time The Scholar Swordsman (雲州大儒俠) appeared on television. Children skipped school, farmers left the fields and workers went home to watch their hero Shih Yen-wen (史艷文) rid the world of evil in the 30-minute daily glove puppetry show. Even those who didn’t speak Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) were hooked. Running from March 2, 1970 until the government banned it in 1974, the show made Shih a household name and breathed new life into the faltering traditional puppetry industry. It wasn’t the first