The Taipei Biennial has served as Taiwan’s major portal to the global art world and most important exhibition of contemporary art since its first international edition in 1998. Through most of its first two decades, the exhibition has been helmed by star curators, mostly from Western Europe, who attempted to use the exhibition for their own grand philosophical statements about the newest and most crucial framings of the human predicament as reflected in contemporary art. Often, however, these globalist curators failed to understand what the world looked like from a Taiwanese perspective.

Now, for this edition of the Taipei Biennial, which opened at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM) on Saturday and runs to March 24, the biennial feels both comfortable with its internationalism and also like it is finding its own voice. It is still plagued by the foibles of contemporary art –– an obsession with theory, artworks that rely on explanation rather than emotional or sensory experience, and general apathy towards notions of beauty –– but at least now it feels more like Taiwan’s own version of this elitist, intellectual enterprise.

NEW DIRECTION

Photo: David Frazier

Last weekend’s opening attracted hundreds of culturati from Taiwan and around the world. Notably perhaps, for the first time ever the afterparty was held in the museum, with hundreds drinking and dancing in a B1 courtyard to the music of DJs Katrina and Sprinkles. (If you know anything about Taiwanese bureaucracy, a public institution staying open past 10pm is a major sea change, and TFAM director Wang Jun-jieh (王俊傑) is to be credited.)

The exhibition fills three floors of TFAM’s galleries with work by 58 artists, and also includes cinema and music programs that will provide event-based programs for the entirety of the four-month exhibition period. Artworks include 11 new commissions, dozens of recent works and also a selection of archival works from the 1950s to the 1980s the curators believe still have value today.

Music programs will feature sets by experimental turntablists (Dec. 10 to 16), musical collaborations with Indonesian migrant laborers (Jan. 7 to 27), and three-day residencies for local non-mainstream musicians focusing on improvisation (Feb. 21 to March 17).

Photo: David Frazier

This Taipei Biennial is also the most Asia-focused to date, featuring at least 19 artists representing Taiwan, Hong Kong, China and overseas Chinese as well as major contingents from Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

At the same time, there are no real Western “art stars” –– and to be honest, it doesn’t feel like one is missing much by their absence.

The exhibition’s makeup is a result of the selection of curators, which steered away from Western European silverbacks and opted instead for a team of three relatively young curators: Taiwan’s Freya Chou (周安曼), who’s served as assistant curator at multiple Taipei Biennials since 2008, Brian Kuan Wood, US-based co-founder of the highly influential online journal of contemporary art, e-flux, and Reem Shadid, director of the Beirut Art Center.

Photo: David Frazier

‘SMALL WORLD’

This exhibition theme chosen by this curatorial trio, “Small World,” is one for life in post-pandemic times and the age of social media.

“Small World,” the curators tell us in their exhibition statement, “suggests both a promise and a threat: a promise of greater control over one’s own life, and a threat of isolation from a larger community.”

Photo: David Frazier

It very much reacts to a world in which tech entrepreneurs promise us unlimited self-enablement, while at the same time human societies are encountering new epidemics of loneliness and mental health. Our “feelings of vulnerability and omnipotence,” the curator statement reads, have become “strangely interchangeable.”

The selection of artworks bundled under this guiding concept is often confoundingly eclectic. (At the opening, one long-time biennial observer commented, “It feels more like an art fair. The way the exhibition is designed, the works don’t really speak to each other.”) Often, the gallery design feels rather random.

Yet there are several threads that, even if they are woven loosely, nevertheless run through the exhibition. These include virtual realities and artificial intelligence, views of the world through the lenses of technology and science, dehumanization, neo-Marxist ideas of labor and exploitation and music as a source of social strategies.

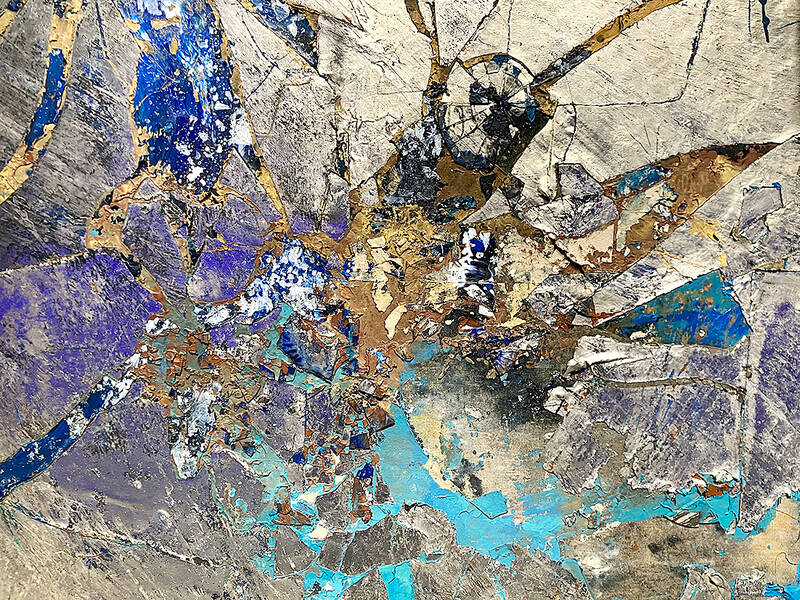

Photo: David Frazier

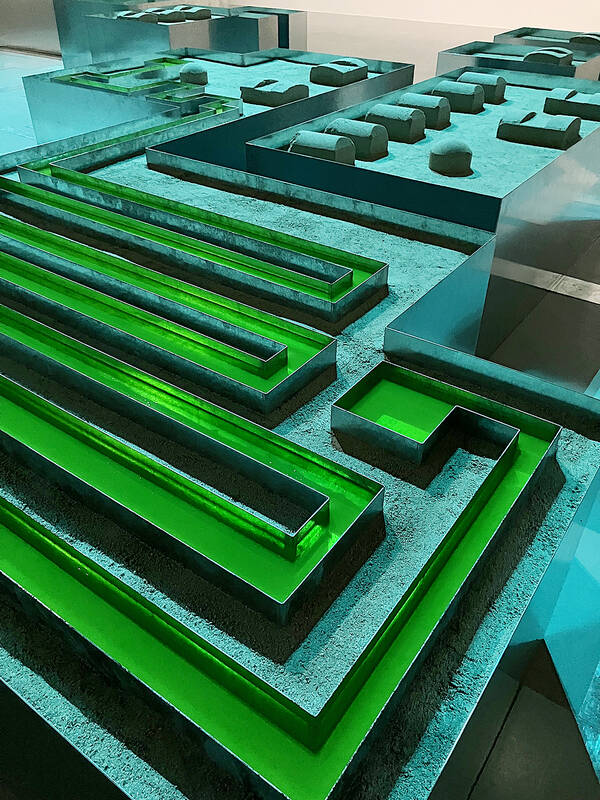

One of the exhibition’s most successful sections reflects Taiwan’s global preeminence as a manufacturer of computer chips by grouping several works. One is the short film Particular Waters by Taiwanese director Su Yu-hsin (蘇郁心), a humanistic portrait of one of the white-suited workers in Hsinchu’s semiconductor fabs. An adjacent gallery holds Naddim Abass’s Pilgrim in the Microworld, a large installation of a maze-like arrangement of stainless-steel-sided sandboxes and channels of fluorescent yellow liquid; when one mounts the stairs to view it from above, one discovers that it resembles a printed circuit board.

Also in the same gallery is Patricia L. Boyd’s Operator, a video from a camera rig programmed to automatically scan some unknown surface, which I at first mistook for the surface of an asteroid though it revealed itself to be the floor of some institutional space. Either way, the video work is about a type of mechanical seeing that has nothing human about it at all. It is merely a way of collecting data.

On another wall of the same gallery are a long row of photographs from Paul Virilio’s series Bunker Archeology from the 1950s and 1960s. Virilio, who died in 2018 and was known primarily as a philosopher of technology, in the post-war years took black and white photographs of abandoned Nazi bunkers along France’s Atlantic coast, later exhibiting them and publishing a book of essays also using the same title. Though the bunkers were once a part of the Nazi war machine and Fortress Europa, he only ever personally experienced them in their state of obsolescence and abandonment. For him, their archeology revealed a history of a certain technology –– mechanized warfare –– that pushed itself to its limit and ultimately burned itself out, leaving only these haunting, discarded reminders.

Photo: David Frazier

This sentiment of the promise and ultimate failure of technology serves as the Biennial’s most primary substrate.

‘RESISTANCE TO SCALE’

One solution of the curators of “Small World” offer is a “resistance to scale” –– and by this they clearly intend a critique of the idea of “scalability” so universally championed in Silicon Valley. Specifically, this is the idea that any innovation worth developing should hold the potential to be rolled out at unlimited scale so that it may influence (and be sold to) all humanity.

In opposition to such enforced homogenization, the curators look to find strength in close-knit groups, underground scenes and other communities rooted in particular circumstances and local realities.

Examples here include Filipino artist Pio Abad’s collection of poetry in Ivatan, a dying language of islands in the northern Philippines closely related to the indigenous tongue still spoken on Taiwan’s Orchid Island. One of these poems is exhibited in letters made of earth, filling one of the galleries.

Another is Hostbuster series of music happenings hosted by Indonesian musicians Julian Abraham “Togar” and Wok the Rock. Over a month, they will reach out to the hundreds of thousands of Indonesian migrant laborers in Taiwan –– who already have formed numerous bands and even their own music festival –– and invite them into the museum for jam sessions, karaoke parties, radio broadcasts, concerts and hangouts.

In very real terms, this represents the radical inclusion of a marginalized Taiwanese population into one of its more esteemed institutions. At present, Indonesian laborers in Taiwan are mainly visible in west coast factory towns and on Sundays in the hidden restaurant shacks near Taipei Main Station. I very much look forward to them coming to play grindcore in the Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern