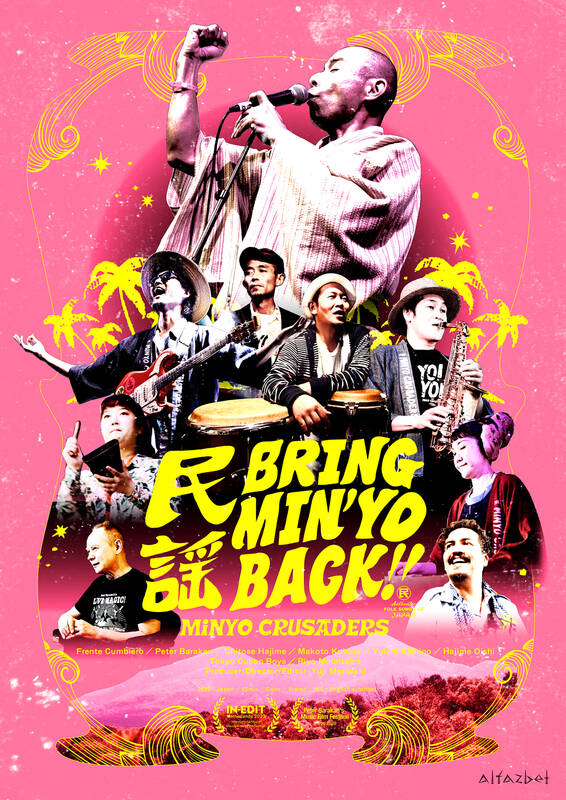

In this age of universal connectivity, the cross-mixing of global musical cultures continues to spawn new and unexpected chimeras. One of the more recent is Japanese cumbia, which in the hands of a Tokyo band called the Minyo Crusaders has brought about the fusion of pre-World War II Japanese folk music and Latin cumbia rhythms. Their story is told in Bring Minyo Back, a new documentary by director Yuji Moriwaki, which screens tomorrow as part of the International Labor Film Festival in Taipei.

Moriwaki’s film is not only a delight to watch and will likely leave audiences tapping their feet in the aisles, it is also a fascinating portrait of how disparate cultural elements combine into new musical forms, a process involving revival movements, the scouring of archives and global information flows.

The Minyo Crusaders, who formed in 2011 and include eight to 10 or more members (depending on the gig), saw their first international release in 2019’s Echoes of Japan. The record quickly claimed the top spot in the Transglobal World Music Chart and propelled the band on to perform at some of the globe’s top world music showcases, including major festivals in Europe, Australia and throughout Asia. They even won a fan in Ry Cooder, who described them as “the best band I have heard in many years.”

Photo courtesy of International Labor Film Festival

On stage, band members dress in an eclectic mix of traditional kimonos and the hipster chic of aloha shirts and fedora hats.

BANANA HOUSE

Their story began in a communal pad called the Banana House in the Tokyo suburb of Fussa, the former site of a US air base. Infused with American influence during the 1960s and 1970s, Fussa became a minor hotbed of pop culture, producing musicians like Eiichi Ohtaki and Haruomi Hosono –– a heritage that band members are aware of and actively cherish.

Photo courtesy of International Labor Film Festival

The group’s musicians came from a variety of backgrounds, but found a common mission in their unique and hybrid brand of folk revival. Lead vocalist Freddy Tsukamoto started out as a jazz singer, while female vocalist and pianica player Meg trained in opera. Other members came via reggae, ska, afro-beat and Latin rhythms. Yet somehow they all shared a fascination with the scratchy sounds of minyo and a desire to see it not completely lost to the popular imagination.

Minyo literally translates as “folk songs” and is a cognate for the Chinese minyao (民謠), which has the same meaning. Yet as with all long-lived musical genres, the character of Japanese minyo shifted from decade to decade. At the earliest, it designated the harvest festival chants and fisherman’s songs of a pre-industrial, agrarian Japan. It was full of regional dialects and locally famous singers, and film’s map animations dot the location of local varieties all up and down Japan, from the north of Honshu down to the southern islands of Okinawa.

Much of Japan’s pop music of the 1950s and 1960s is now retroactively dubbed minyo. Though vocal lines of this pop music often stuck to traditional techniques that produce quavering, nasal melodies, this music of the post-war years incorporated more American and international influences than earlier, more traditional Japanese folk songs. It began to feature brassy horn fills and the swinging rhythms of jazz. The post-war years also saw early examples of minyo-Latin fusion in groups like the Tokyo Cuban Boys and singers like Eri Chiemi, who performed with a number of Western big bands including the Count Basie Orchestra.

Photo courtesy of International Labor Film Festival

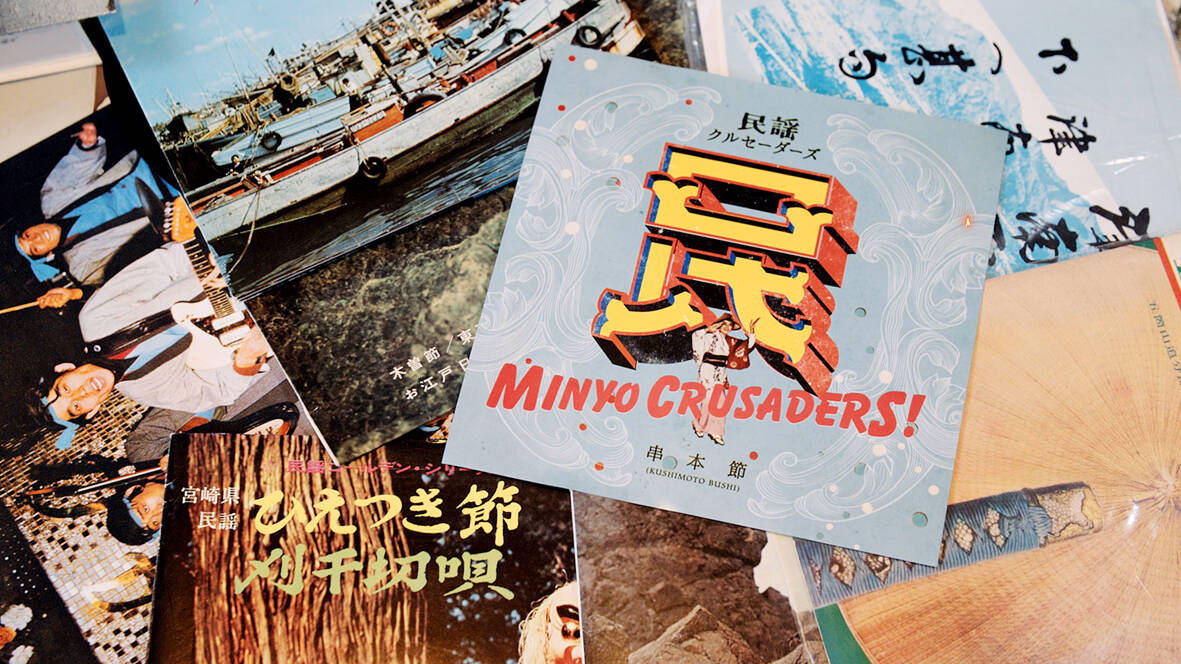

The documentary renders these voyages into the musical past by following the Minyo Crusaders’ hipster crew to buy armfulls of these old records in junk shops, as even used record stores no longer bother to sell them.

Minyo more or less died, the film claims, by the 1980s, that decade of the profusion of cassette tapes, synthesizers and a globalized pop culture. As a result, the musical form devolved from a living form to a museum piece, surviving under state-sponsored competitions and stiff organizations for formal singing. One elder musician laments that there are no young people to replace his like in the traditional performance troupes.

‘BRING MINYO BACK’

Photo courtesy of International Labor Film Festival

Sensing this crisis of traditional culture, Minyo Crusaders band members profess a fervent desire to “bring Minyo back.” Yet at the same time, they are fully cognizant that tradition must be updated if it is to find favor with contemporary audiences.

Their bizarre but wonderful solution is to create a fusion music of traditional Japanese songs with cumbia and other Latin and afro-caribbean styles.

How they arrive at this formulation is not completely made clear in the film, but one gets the sense of musicians confronting the global glut of information in which everything is everything, and then, as they examine the question of identity and ask, “Who am I really?”, they turn back to the roots of their own culture.

One expert describes foreign rhythms and genres as “fashions” that more or less come and go, while one’s own traditions, he claims, are “akin to a religion or cultural lifeblood.”

Cumbia then becomes a sort of globally circulating meme that allows them to reinvent their own tradition. And though Japanese cumbia perhaps sounds like an odd juxtaposition, other similarly odd folk revivals are now happening all throughout Asia. The Korean reggae of NST & Soul Sauce, the Indonesian folk-electronica of Bottlesmoker and the Buddhist metal of Taiwan’s Dharma are just a few examples.

Cumbia’s passage in Japan is not fully dealt with in the film, but it is an interesting one.

CUMBIA ORIGINS

According to Tokyo-based music promoter Shogo Komiyama, from the 1980s and 1990s, cumbia began to emerge in Japan’s scatalogical music underground through disparate trickling channels, which have lately converged to form a river.

“Now in Tokyo, everyone is a cumbia DJ,” he grimaces.

Komiyama was born to Japanese parents in Argentina and recalls listening to his father’s collection of cumbia and chamame, a kind of Paraguayan polka, which was played around the house every weekend.

In 1986, he emigrated to Japan, and in 1999 began importing Latin musical performances through his promotional groups Japonicus and Radical Music Network. Almost from the very start, he also began working with the Fuji Rock Festival, Japan’s largest international showcase, which over the last 25 years has become a major platform introducing cumbia and other Latin music.

“Nobody knew about cumbia when I came over. So I started burning CDs and giving them to ska and reggae DJs, who began mixing the songs into their sets,” said Komiyama, reached by phone at his home in Tokyo.

Komiyama found a like minded aficionado of cumbia in Fuji Rock’s British music director, Jason Mayall, son of the famed blues guitarist John Mayall.

Mayall had since the 1980s been digging cumbia 45s in Colombia, then bringing them back to London and spreading them around on cassette mix tapes. In the 2007 documentary, Joe Strummer: The Future is Unwritten, Mayall is filmed presenting one of these mixtapes to the Clash frontman Strummer himself, who, kissing the cassette, declares, “We love it. We play it all the time.”

In recent years, Mayall has DJed at Fuji Rock under the moniker “The Cumbia Kid.”

The Minyo Crusaders tapped into Japan’s cumbia infusion just over a decade ago, combining it with Japanese folk to make music in their own unique formula.

One of the more fascinating parts of the film is its latter section, in which the Minyo Crusaders take their Japanese cumbia back to Columbia where they collaborate with like-minded revivalists, the Bogota band Friente Cumbiero.

Here we learn that in Columbia, cumbia saw its peak as pop music in the 1960s, only to be replaced by more recent forms of Latin pop. Today, its threads continue to be woven through Colombia’s musical culture as electronic dance beats and traditionalist players.

This section of the film is essentially a concert video, a montage of performances and jam sessions, but the music is just tremendous and a joy to watch.

Bring Minyo Back is one of 21 film programs in the 2023 International Labor Film Festival (國際勞工影展). The festival runs online until Nov. 14, with physical screenings today and tomorrow at the Eslite Art House Cinema in Taipei’s Songshan Creative Park.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the