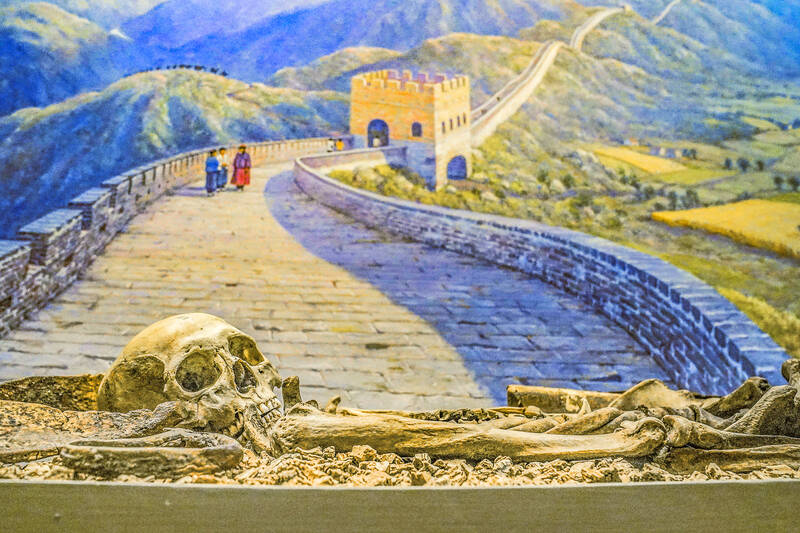

There are stories in the human bones at the American Museum of Natural History. They tell of lives lived — some mere decades ago, others in past centuries — in cultures around the world.

But the vast collection of thousands of skeletal parts at one of the world’s most visited museums also tells a darker story — of opened graves, disrupted burial sites and collecting practices that treated some cultures and people as objects to be gawked at.

The New York museum announced this month that it is pulling all human remains from public display and will change how it maintains its collection of body parts with the aim of eventually repatriating as much as it can and respectfully holding what it can’t.

Photo: AP

The museum now holds around 12,000 sets of remains, including the bones of indigenous people and enslaved black people, often amassed in the 19th and 20th centuries by researchers looking to prove theories about racial superiority and inferiority through physical attributes.

Some of the other remains are people — likely poor or powerless — whose bodies had once been used at medical schools before they were given to the museum as recently as the 1940s.

American Museum of Natural History President Sean Decatur, who in April became the museum’s first black leader, said that for the most part, the remains in the collection were acquired without clear consent of the dead or their descendants.

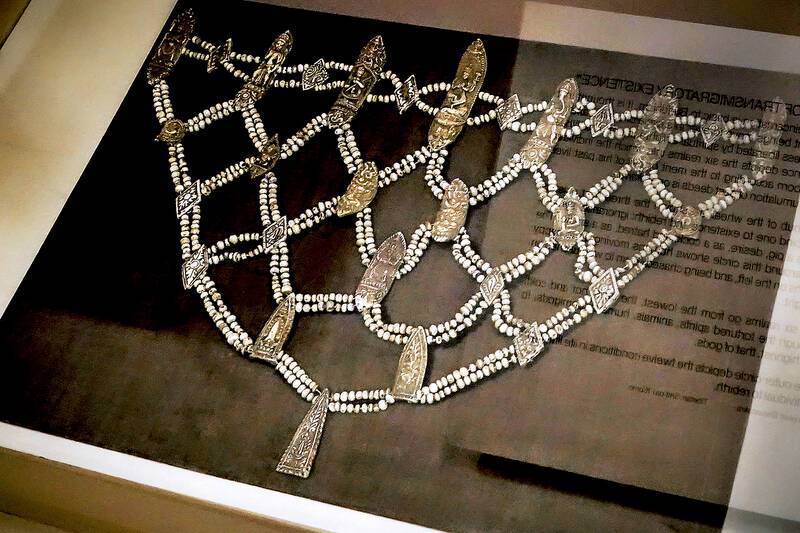

Photo: AP

“I think it’s fair to say that none of these people set out or imagined that their resting place would be in the museum’s collection,” he said. “And in most of the cases, there also was a clear differential in power between those who were collecting and those who were collected.”

RETURNING TAKEN ARTIFACTS

The process of pulling human remains from public display will impact six of the museum’s galleries. Objects being removed include a musical instrument made from human bone, a skeleton from Mongolia that is more than a thousand years old and a Tibetan artifact that incorporates bones.

The idea that human remains and artifacts taken from other cultures should be returned is not new. A US law passed in 1990 created a legal process for some Native American tribes to recover ancestral remains from museums and other institutions. In a letter to museum staff, Decatur said about 2,200 sets of remains at the museum fall under that category.

Other museums and institutions are grappling with the issue as well. At the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, for example, more than 100 human remains have been returned to the relevant communities. The museum is working to return four other sets of remains that don’t fall under the federal law’s purview.

“Fundamentally, we have a responsibility to do more than acknowledge the harm caused by historical collecting practices that treated peoples and cultures as objects of scientific study,” Chris Patrello, curator of anthropology at the museum, said in an E-mail.

As of last year, an estimated 870,000 Native American artifacts, including remains that should be returned to tribes under federal law are still in possession of colleges, museums, and other institutions across the country.

But its not just indigenous remains being in museum collections that are troubling.

Decatur said some of the remains in the museum are believed to be of five black people whose bones were removed from a northern Manhattan burial ground during a road construction project at the start of the 1900s.

“Enslavement was a violent, dehumanizing act; removing these remains from their rightful burial place ensured that the denial of basic human dignity would continue even in death,” Decatur said in his letter to the museum staff.

Historically, black graves have been subjected to robbery, said Lynn Rainville, a professor of anthropology at Washington and Lee University. They have also been covered over or disrupted in construction and development projects.

MEDICAL CADAVERS

Decatur said the American Museum of Natural History’s holdings also include about 400 bodies that came from four New York medical schools in the 1940s, even though there’s no obvious process by which bodies used for medical training in anatomy should have ended up in a museum.

One of the medical schools no longer exists; the others were connected to Columbia, Cornell and New York University. Columbia’s medical school had no comment. The other two did not respond to E-mails seeking information. Museum officials said they were talking with the schools and as far as they had been able to determine, the bodies had not come to the institution in any nefarious way.

“It’s one of those things that is jarring and sort of ... hits closer to home than an archaeological expedition that’s looking at things that are a thousand-plus years old. But it’s a practice that was incredibly common” at the time, Decatur said.

Susan Lederer, professor of medical history and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin’s medical school, said that as the number of medical schools increased in the 19th century and dissection became an essential part of training, schools needed to find more cadavers.

States passed laws making unclaimed bodies, mostly of very poor people, available to medical schools.

“It reflects longstanding assumptions about the differences between middle-class and either working-class or underclass people” that it was deemed acceptable to turn certain bodies over but not others, she said.

The practice at most medical schools shifted in the second half of the 20th century for a number of reasons, including more people in the US being willing to donate their bodies after death, she said.

The museum’s process of figuring out how to handle those and other remains in storage will take some time, Decatur said. Officials will need to determine what can be returned and to whom, as well as how to properly care for any remains that stay behind.

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions

In the run-up to World War II, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence service, began to fear that Hitler would launch a war Germany could not win. Deeply disappointed by the sell-out of the Munich Agreement in 1938, Canaris conducted several clandestine operations that were aimed at getting the UK to wake up, invest in defense and actively support the nations Hitler planned to invade. For example, the “Dutch war scare” of January 1939 saw fake intelligence leaked to the British that suggested that Germany was planning to invade the Netherlands in February and acquire airfields

Taiwanese chip-making giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) plans to invest a whopping US$100 billion in the US, after US President Donald Trump threatened to slap tariffs on overseas-made chips. TSMC is the world’s biggest maker of the critical technology that has become the lifeblood of the global economy. This week’s announcement takes the total amount TSMC has pledged to invest in the US to US$165 billion, which the company says is the “largest single foreign direct investment in US history.” It follows Trump’s accusations that Taiwan stole the US chip industry and his threats to impose tariffs of up to 100 percent