It has been rare in the past decade for multiple books in a Taiwanese manga series to be translated into French, but The Lion in Manga Library (獅子藏匿的書屋) by Xiaodao (小島) is one of the few exceptions.

As of Sept. 8, all three books in the award-winning series have been published by the Lyon-based startup publisher, Komogi Editions.

Although the series’ revolvement around the board game “go” suggests it would mainly be of interest to a niche reader base, the 34-year-old manga artist hopes the deeper message of her story will appeal to a wider range of people.

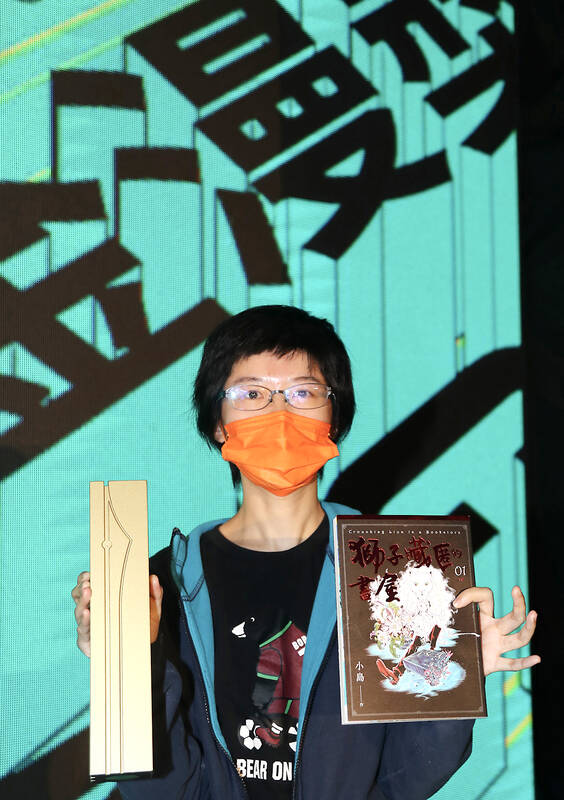

Photo: CNA

Xiaodao shared how the theme of love threads her narrative together, how she explores the challenging dynamics of parent-child relationships in Taiwan and how these themes will play out as the series draws to an end.

TRAUMATIC CHILDHOODS

Set in Taiwan in 2020, the The Lion in Manga Library series (hereafter referred to as Lion) begins with a reunion of two go players — the main characters — who share a common experience of dealing with traumatic parental relationships.

Photo: courtesy of Taiwan Creative Content Agency

Fang Hsia-sheng (方夏生), a 16-year-old Go prodigy who recently won his first pro major title in Taiwan, has managed to escape his mother’s grip and seek temporary refuge in a rental bookstore run by his former go teacher Winter Yuan (元冬季), a 24-year-old former pro master who has not placed stones for a long time.

As the story unfolds, readers soon learn that Yuan and Fang are battling similar demons.

Often given the cold shoulder by her mother during her childhood, Yuan has been plagued by a psychosomatic disorder which led to her pro career coming to an abrupt halt a few years earlier.

The relationship that the two develop is considerably different from the parent-child relationships they endured during their youth, “as different as the black and white stones on the board,” according to Xiaodao.

By the beginning of the third book — which was published in Chinese and French this year — the two have cultivated a romance and are working together to conquer the challenge posed by a go AI developed by Fang’s older brother in order to release the teenager from his family’s grip.

“If those of our generation (around 30) look closely at the relationship they have with their parents, most of them will have [inevitably] experienced similar problems ... because of the suffering that generation endured while growing up,” Xiaodao said when asked about why she chose to focus on this in the series.

The exploration of love, as well as the inclusion of AI and Taiwan’s declining rental bookstore industry, is what differentiates Lion from the go manga classic Hikaru no go by Yumi Hotta and Takeshi Obata, Xiaodao said.

The series by the Japanese manga artists was such a masterpiece that her work would never be able to compete, she added.

However, Xiaodao said it was only when looking back on her work that she realized just how present and significant the theme of love was in her books.

CONDITIONAL LOVE

Originally, Xiaodao said her main idea was to create a story about two individuals brought together by the board game. But as she continued drawing, the scars and shadows plaguing the two characters continued developing.

“Asian parents’ love for their children is based on a kid’s social value,” she said. “How much love you receive depends on how successful you are at school or in society. They’re lying if they say they will love you regardless of what grade you score on a test.”

This means that things like income, job position and relationship status are thrust into the spotlight on occasions like school reunions after people enter their 30s, because people are used to earning love and recognition from others based on their level of success as defined by wider society, Xiaodao added.

These social values led to the conflicts Xiaodao experienced with her family while pursuing her dream of becoming a manga artist.

She said the particularly fierce fights were with her mother, who has never stopped asking her when she was going to get a “proper job,” even after she won the grand prize of the 2021 Golden Comic Awards, the most prestigious manga honor in Taiwan.

“They (mom and dad) had never even heard of it until I won it. Why would they recognize it as an achievement?” she said.

Yet, the cartoonist said she is one of the lucky ones in Taiwan society. Some of her friends had their work torn into pieces by their parents.

Describing these conflicts as common in Northeast Asia, Xiaodao said relentlessly brutal parenting is to blame, but that she could also understand why parents could be like this, “because no one is obliged to back another’s dream.”

Xiaodao said she feels most encouraged when fans tell her how much they appreciate her work. She has no regrets about her career decision, even though that means working as a part-time go teacher and physical therapist to supplement her income.

DREAM JOB CONTINUES

Late last month, Xiaodao revealed that the Ukrainian translation of the first volume of Lion had been completed. She said that she looks forward to meeting her Ukrainian fans and hopes that Kyiv will be victorious in the war.

Although Xiaodao said she is still focusing on the series finale and has no concrete plans for her next work, she was inspired by the performance of professional go player Hsu Hao-hung (許皓鋐) at the Asian Games this year.

Hsu, who was ranked 35th according to the unofficial Go Ratings, upset the world’s top three players in the men’s individual competition in Hangzhou, China on Sept. 28, winning Taiwan’s first Asian Games gold in the board game.

Describing Hsu’s feat as “more dreamlike than manga,” Xiaodao said she would consider modeling her next story on the Hangzhou Asian Games — but only after she completes the Lion series.

“If I do draw the Asian Games, I expect it to be closer to a documentary manga,” she said.

Editor’s note: ‘The Lion in Manga Library’ is the title for the French version of the series, whose original English title was ‘Crouching Lion in a Bookstore’. The first episode in English can be accessed for free at the Books From Taiwan platform.

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislative caucus convener Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) and some in the deep blue camp seem determined to ensure many of the recall campaigns against their lawmakers succeed. Widely known as the “King of Hualien,” Fu also appears to have become the king of the KMT. In theory, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) outranks him, but Han is supposed to be even-handed in negotiations between party caucuses — the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) says he is not — and Fu has been outright ignoring Han. Party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) isn’t taking the lead on anything while Fu

Feb 24 to March 2 It’s said that the entire nation came to a standstill every time The Scholar Swordsman (雲州大儒俠) appeared on television. Children skipped school, farmers left the fields and workers went home to watch their hero Shih Yen-wen (史艷文) rid the world of evil in the 30-minute daily glove puppetry show. Even those who didn’t speak Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) were hooked. Running from March 2, 1970 until the government banned it in 1974, the show made Shih a household name and breathed new life into the faltering traditional puppetry industry. It wasn’t the first

US President Donald Trump’s threat of tariffs on semiconductor chips has complicated Taiwan’s bid to remain a global powerhouse in the critical sector and stay onside with key backer Washington, analysts said. Since taking office last month, Trump has warned of sweeping tariffs against some of his country’s biggest trade partners to push companies to shift manufacturing to the US and reduce its huge trade deficit. The latest levies announced last week include a 25 percent, or higher, tax on imported chips, which are used in everything from smartphones to missiles. Taiwan produces more than half of the world’s chips and nearly all