In late 1909, the Ho family faced a dilemma. Mired in arrears on the rent for their modest rice patch in Tanwen village (談文), present-day Miaoli County (苗栗縣), the tenant farmers received a modest proposal: their son in exchange for a clean slate. They accepted, and the boy was adopted by Ho Chai-wu (何宅五, no relation), a wealthy merchant from Hsinchu City (新竹).

Sixty years later, the adoptee — who had become an acclaimed painter in Japan — would lament the circumstances that saw him torn from his family and, ultimately, his homeland.

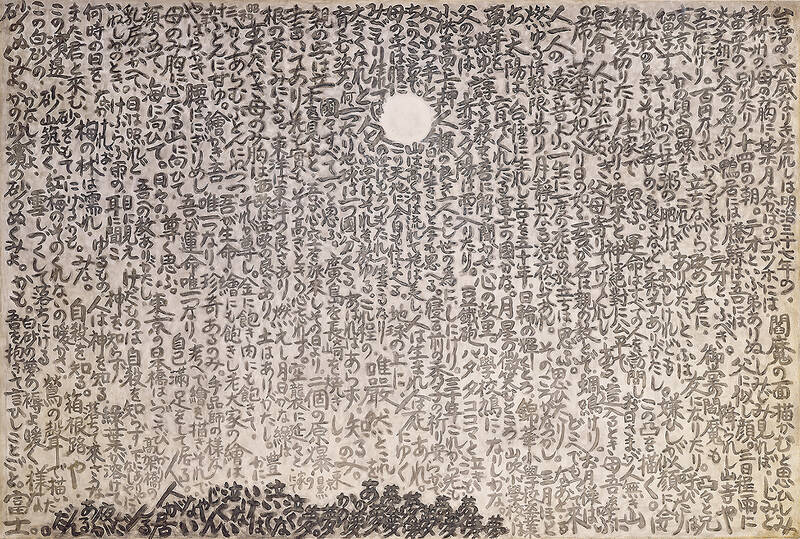

“Born in Taiwan,” begins the text on Fifty-Five Waka Poems (五十五首歌), a painting by Ho Te-lai (何德來) that features in the artist’s first Taiwan retrospective in almost 30 years. “Mother painfully had me adopted away at age six; sent off to study in Tokyo at age nine.”

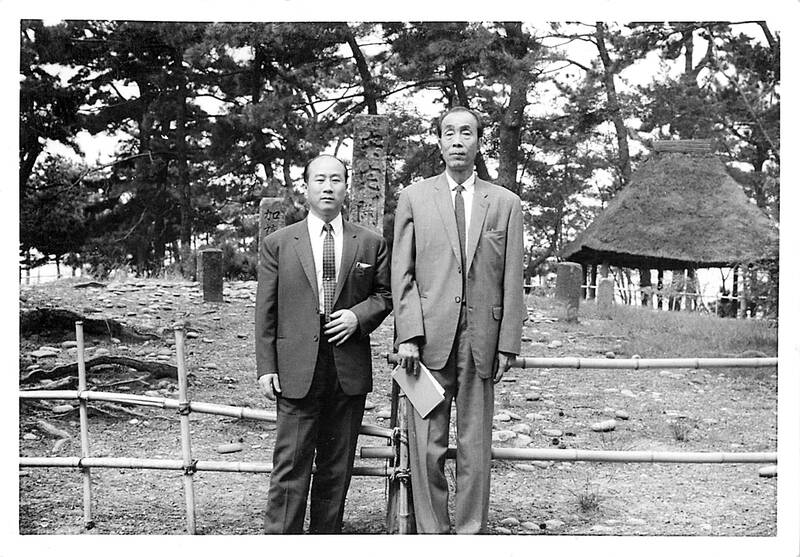

Photo courtesy of Ho Han-chiang

Such plaintive reflections on a traumatic dislocation pervade the exhibition, which runs at Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM) until Oct. 22. Unlike Ho’s previous retrospective at the museum in 1994, this one, titled “Keeping to My Path,” uses his Japanese name, Ka Tokurai.

This was a calculated decision. “It shows his two identities,” Jane Chan (詹美倫), who provides English-language tours of the exhibition on Thursdays and Saturdays, says. “While he lived most of his life in Japan, he was always thinking of Taiwan. This is reflected in his work.”

The most obvious example of this yearning is the painting Mother and Son (吾之生) from 1958, which is executed in an almost naive style. The rounded contours of the central characters and objects and the soft golden hue of the peasant abode, dimly illuminated by a glowing oil lamp, communicate comfort, shelter and contentment. Perched on the mother’s knee, clutching her arm, the pudgy, oversized infant is lost in distant contemplation. The Chinese character for happiness, doubled up for emphasis, (囍) can be seen on the child’s bib. On either side of a window, through which a farmer can be seen half-immersed in flooded paddy, two traditional red scrolls are emblazoned with entreaties to “love friends” (愛友) and “respect the gods” (敬神).

Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

The view from the window looks more like painting than a real scene, and Chan notes the overall dreamlike quality of the work.

“It’s unreal, like an idealized version of happiness,” she says. “Maybe that was his way to heal the grief he felt.”

FAMILY CONNECTION

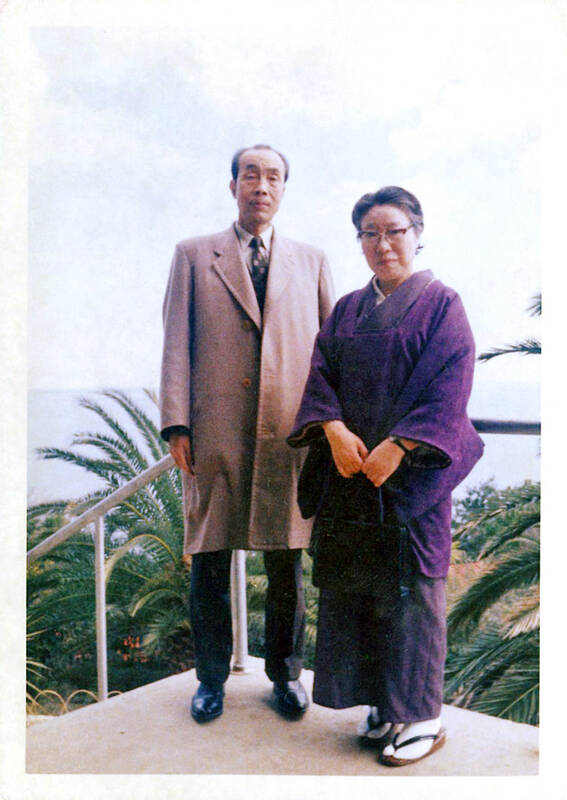

Photo courtesy of Ho Han-chiang

I first encountered Ho’s work circa 2002 at an exhibition on Japanese-era painters in Taipei. On my return to Miaoli, where I then lived, I was astonished to discover the painter — who remains little-known to the Taiwanese public — was the biological great-uncle of my soon-to-be father-in-law Ho Han-chiang (何漢強). He told me the little he knew about his talented relative, as the family had maintained tenuous and intermittent contact with the relatives of Ho Te-lai’s adoptive father, Ho Chai-wu.

“He was childless,” Ho Han-chiang says of the merchant. “It might seem sad, but it was common in those days [to give your child up for adoption]. Great-uncle never forgot his blood family.”

Over the years, I pieced together the backstory, trawling photo archives at Ho Han-chiang’s home in Jianshan village (尖山) on the outskirts of Toufen (頭份) in Miaoli; visiting nearby Tanwen, the artist’s birthplace, and most importantly, speaking to Ho Teng-ching (何騰鯨), the painter’s nephew who died in his mid-90s in 2020.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Ho Te-lai was sent to Tokyo for elementary school and returned later to Taiwan, graduating in 1921 from Taichung Municipal First Senior High School (台中一中), established six years earlier by Taiwan’s gentry as the first high school for Taiwanese children under Japanese colonial rule.

EXPERIMENTAL SOUL

As the first Taiwanese to top the entrance exam for Tokyo Fine Arts School — now Tokyo University of the Arts — Ho enrolled in the Western oil painting program, but graduated with poor grades and a reputation for nonconformity. Embarking on his professional career, he joined the Shinkouzou movement, a loose-knit collective of experimenters.

Photo courtesy of Ho Han-chiang

While the group worked to Western-influenced standards dominating Japanese (and, in turn, Taiwanese) oil painting in the 1930s, it emphasized freedom in form and content. Ho’s work is a testament to this. From his earliest known painting in 1920 — a trio of veiled nuns beckoned by a cherub, entitled The Sacred Maidens (聖女們) — to the en plein air period of his twilight years, Ho showed remarkable eclecticism.

His output during the 1950s and 1960s demonstrates such breadth that it is hard to believe it came from the brush of a single artist. A rendering of Mount Fuji, its slopes delineated with thick pink strokes, reveals Fauvist influences; early self-portraits and still-lifes are rendered in classical representational fashion. And pieces such as the serene, minimalist At Dawn (黎明), from 1962, look more like woodcut prints than oil works.

CALLIGRAPHIC MASTERPIECE

While Ho didn’t really have “periods,” recurring motifs emerge: mortality, as in the 1951 work Temptation of Death (死之誘布); light representing life, exemplified in a series of blazing suns with scintillating rays painted over a 10-year period from 1957, and threats to and from humanity through impending Malthusian catastrophe and war.

These last two themes are tackled in The Overpopulated Earth (人滿為患的地球) and Post War (戰後), both from 1950.

Text and calligraphy are incorporated into works, particularly Japanese waka poetry, of which there are several forms, all — like Haiku — comprising units with lines of 5 and 7 syllables. Considered by many his masterpiece, Fifty-five Waka Poems is the example par excellence. Here, the biographical calligraphy creates a gray backdrop with darker characters forming a hillside at the bottom of the painting. A circular gap in the text lets in a shimmering moon.

“Go write some poetry!” Ho told his Shinkouzou associates as they searched for inspiration. He often began painting sessions by penning verse.

LOST LOVE

One of the most important themes is Ho’s love for his wife Hideko, a noted shaminsen (three-stringed lute) player who he lost to cancer in 1973. An expressionist, slightly mournful portrait of Hideko in the traditional kneeling pose adopted to play the instrument is displayed toward the back of the gallery, and the exhibition’s name is taken from a collection of poems Ho dedicated to her.

Ho returned intermittently to Taiwan, including a three-year stint in the early 1930s when he established the Hsinchu Art Research Society (新竹美術研究會) with acclaimed watercolorist Lee Tze-fan (李澤藩). A sketch in the opening room of the exhibition, which Ho had given to his friend, was donated to the museum by the Lee family. Works depicting Ho’s family home and the Hsinchu countryside from this period also feature.

Yet, the recognition Ho gained in Japan was not replicated in his homeland. Nearly 60 Japanese flew to Taiwan for the opening of the 1994 exhibition, where Shinkouzou members spoke reverently of the old maestro. Meanwhile, a smaller retrospective was held at the Taiwan Cultural Center in Tokyo in 2018 to coincide with an exhibition for the 90th anniversary of the Shinkouzou group.

JOYFUL RETURN

Like most Taiwan-born individuals from the colonial era, Ho was a Japanese subject, and following decades of residence in Japan, he was eligible for full citizenship. His decision to forego naturalization stemmed from his attachment to Taiwan, his nephew Teng-ching, who had dual nationality, said. “He always felt Taiwanese at heart.”

Teng-ching had also sailed for Japan as a youngster, though under very different circumstances, absconding almost penniless after a family row. Starting as a lowly kitchen hand, he eventually made his fortune operating Pachinko parlors.

Having maintained relations with his birth family, Ho Te-lai formed a close bond with his nephew. The pair were physical opposites — Te-lai, beanpole tall and austere-looking; Teng-ching, soft and diminutive. Appearances and age gap aside, the relationship was was fraternal. “Van Gogh had his Theo, and I my Teng-ching,” runs another line from Fifty-five Waka Poems.

Unlike Theo, Ho Te-ching professed to understand little about art; yet he knew the stock his uncle place in his work. Upon Ho Te-lai’s death in 1986, Teng-ching inherited his uncle’s oeuvre and instructions that nothing should be sold — a life-long principle for the painter.

Teng-ching recalled the time a collector offered a princely sum for a small painting of a toad. The night before the sale, the amphibian confronted the artist in a dream, pleading not to be sold. The miniature features in this exhibition.

In 1994, following lengthy discussions, Teng-ching donated most the collection to TFAM.

“I knew they would be cared for and my uncle would have been happy,” Teng-ching said. “It was like he’d finally returned home.”

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislative caucus convener Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) and some in the deep blue camp seem determined to ensure many of the recall campaigns against their lawmakers succeed. Widely known as the “King of Hualien,” Fu also appears to have become the king of the KMT. In theory, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) outranks him, but Han is supposed to be even-handed in negotiations between party caucuses — the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) says he is not — and Fu has been outright ignoring Han. Party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) isn’t taking the lead on anything while Fu