In Taiwan’s English-speaking circles, quite a few people are familiar with the names Clarissa Wei (魏貝珊) and Ivy Chen (陳淑娥). California-born Wei has been writing about local food and other subjects for several years. Among expats and tourists, Chen is a go-to teacher of Taiwanese and Chinese cuisine.

Both women live in Taipei, but as Wei explains early on in Made in Taiwan: Recipes and Stories from the Island Nation both have roots in the south of the island. Wei’s parents immigrated to the US from Tainan. Chen was brought up in a small town a short distance north of the former capital.

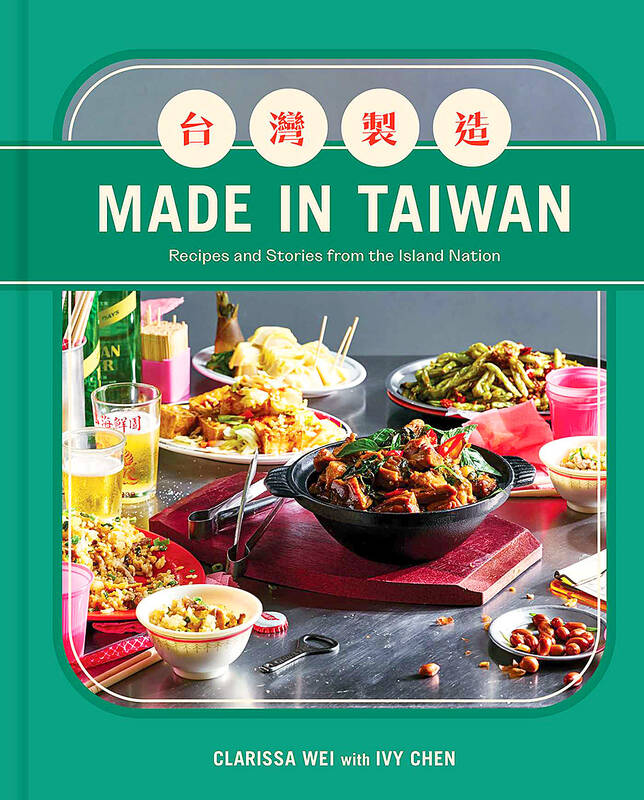

Like every supporter of Taiwan, this reviewer welcomes any English-language book about the country that’s reasonably accurate, especially if it has some potential to attract the interest of people overseas who wouldn’t normally spare a thought for this island. Made in Taiwan certainly has that. It’s very well written and, as far as I can tell from the electronic version I received, it’s filled with good photographs. But if you’re an apolitical foodie in London or Vancouver, you just might put it down before getting as far as Chen’s recipes.

The only text on the frontispiece is a “what makes a nation?” quote from Peng Ming-min’s (彭明敏) A Taste of Freedom. (That book isn’t about food, despite “taste” being in the title.) Before you reach the end of the first paragraph of the introduction, you know exactly where Wei stands on the Taiwan/China issue. Turn the page, and she’s reminding you of Beijing’s crimes against the Tibetans and the Uighurs. In all of this, there’s nothing I disagree with. It’s just that I wonder if it might not have the desired effect on bookstore browsers.

Actually, there is one thing that grates. Wei explains that “the whole point of this book is to tell the story of Taiwan as best as we can before it’s too late. Unfortunately, the odds are not in our favor.” I’ve always believed that steely confidence is an essential response to Chinese Communist Party (CCP) claims that unification is inevitable. Before I’d got to any food descriptions, this defeatism had left a bad taste in my mouth.

The following section, on Taiwan’s culinary history, is brief yet engaging. Without telling us why certain crops grow well here — there’s nothing about average temperature or rainfall, or at what elevation aiyu (愛玉, jelly fig) grows — Wei outlines how each wave of arrivals broadened the food spectrum.

I didn’t know that some researchers think deep-frying may have been introduced by the Dutch during their mid-17th century occupation. I’m not convinced by her assertion that Taiwan’s mountainous topography is why “the pig — which doesn’t need a lot of space — is our de facto protein.” The country lacks large areas of grazing land, that’s true, but pigs are among the few large animals that can endure lowland summers without artificial cooling, and until recently they didn’t require massive feed imports. I still can’t quite believe that the Hakka were, according to Wei, “some of the first people to raise domesticated pigs” in Taiwan.

In the subsection titled “A New Taiwanese Identity (1980-Today),” there’s nothing about the hundreds of thousands of Southeast Asians who’ve become citizens and who cook meals for their Taiwanese spouses, children and in-laws. Is it too early to say something about the foodways they’ve brought to the country? Perhaps.

If you plan to make proper Taiwanese dishes, the segments that explain what equipment you’ll need and what items you should have in your pantry are essential reading. Even if you don’t — but you happen to be living in Taiwan and are curious about what goes into the food you eat every day — you’ll likely find the descriptions of the various pastes, sauces, starches and vinegars highly interesting. Some Westerners speak of MSG as if it’s kryptonite; the authors of Made in Taiwan are agnostic on the issue.

Wei points out that lard is “the core ingredient many swear on for flavor’s sake.” This matches my understanding of traditional cooking in Taiwan, and it’s a major difference between Ivy Chen’s recipes and the lard-free versions in Cathy Erway’s 2015 cookbook The Food of Taiwan. Erway has done a lot to popularize Taiwanese cuisine outside the country, but when it comes to lard, I think Chen and Wei take the right approach.

Predictably, Made in Taiwan tells us how to make beef noodle soup (紅燒牛肉麵) and tofu with century egg (皮蛋豆腐). The authors have included a slew of night-market favorites like oyster omelet (蚵仔煎) and (for this I admire their audacity) black pepper steak and spaghetti (鐵板牛排麵). Vegan blood cake (智慧糕) isn’t a concession to those who’ve sworn off animal foods, but an alternative crafted “because it’s really difficult for the average home cook to get access to fresh blood.” Indigenous and Hakka dishes are here, as they should be.

Chen’s recipe for fried shrimp rolls (蝦捲) is sure to satisfy old-schoolers, because it sets out the option of wrapping the rolls in caul fat rather than tofu sheets. The pan-fried noodle cake (麵線煎) especially intrigued me, as I think this is something I’ve never seen, let alone eaten, in my three decades in Taiwan.

The people we meet through this book — such as the “pickling queen” in Yunlin County and an octogenarian maker of scallion pancakes (蔥油餅) — are treasures who deserves to have their stories told. And they’re not all old-timers about to leave this world and take their knowledge with them. The rapper who sells braised minced pork on rice (肉燥飯) and the couple who’ve chosen to specialize in rice-based pastries known as kueh (粿) are among reasons to believe local cuisine has a bright future.

These profiles, the in-recipe asides and the feature articles that tread familiar ground, are what really make this book an enjoyable and very worthwhile read. Even if you’ve no intention of firing up your stove.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,