The bodycam footage of police shooting undocumented Vietnamese migrant worker Nguyen Quoc Phi nine times isn’t the most harrowing scene in And Miles to go Before I Sleep (九槍) — it’s the ensuing moments, which feels like a suffocating eternity, where Nguyen is left naked on the ground to bleed out.

An ambulance arrives and inexplicably takes a person who was punched in the nose by Nguyen to the hospital first, while officer Chen Chung-wen (陳崇文) repeatedly tells those at the scene not to approach the seriously injured Nguyen because he’s dangerous.

This controversial case from 2017 touches upon numerous topics, from appropriate use of police force to migrant worker mistreatment and racism. Nguyen, who was allegedly on drugs, refused to comply with police and attempted to steal a patrol car. He later succumbed to his wounds, while Chen was convicted of negligent manslaughter. He avoided jail time and settled with Nguyen’s family out of court. Meanwhile, the Hsinchu County Police Bureau was censured for “inadequate training” leading to the use of excessive force, delay in getting medical help and tampering with crime scene evidence.

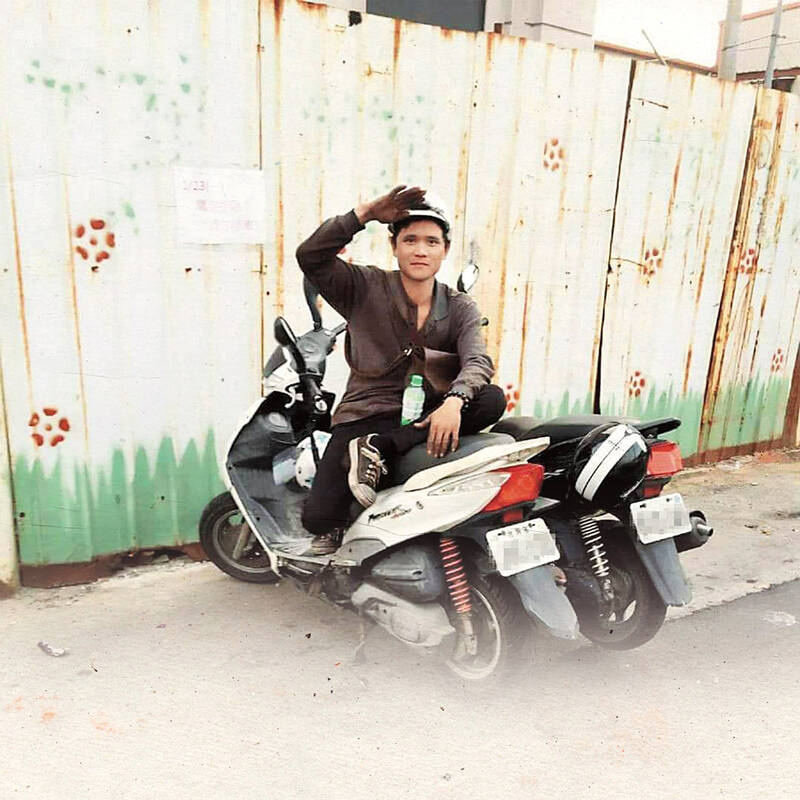

Photo courtesy of And Miles to go Before I Sleep

Both sides have their supporters. Chen reportedly already used pepper spray and his baton on Nguyen before pulling his firearm, and police reluctance to use their guns for fear of such repercussions has been a point of contention whenever an officer is killed by a suspect. To Chen’s family and advocates, Nguyen was a drug-addicted criminal who attacked first, and Chen should not be punished for simply for doing his job.

This perspective is only slightly touched upon in the film, as it mostly avoids getting into the argument of who’s right or wrong. The shooting mostly serves as a vehicle to humanize Nguyen and explain the complicated circumstances that drove him and countless others to desperation.

As director Tsai Tsung-lung (蔡崇隆) said in an interview: “What killed Nguyen Quoc Phi wasn’t merely those nine shots.”

Photo courtesy of And Miles to go Before I Sleep

Tsai interviews Nguyen’s family in Vietnam, speaks to his coworkers in Taiwan and intersperses emotional excerpts from Nguyen’s Facebook posts about his hardships in Taiwan, his hopes for the future and his yearning for his family. Context is provided through interviews with lawyers, brokers and agencies involved in the hiring of migrant workers, as well as scenes of the various incidents and tragedies involving migrant workers over the years, as well as protests held against their exploitation and abuse.

Mixing calm, atmospheric shots with interviews and news footage, And Miles to go Before I Sleep weaves together a sympathetic, but not overly sentimental portrait of Nguyen and others who have suffered similar fates. These workers don’t run away for no reason. In Nguyen’s case he was ripped off by his broker and paid significantly less than promised, leading him to flee for better opportunities. Tsai doesn’t go into detail, but provides just enough context to give the viewer a general idea of the issue.

One element that’s largely missing is a discussion about racism toward Southeast Asians. For example, how did it play a part in the police’s seemingly callous actions, especially after the shooting? Endemic discrimination toward migrant workers are briefly mentioned, but the viewers are left to draw their own conclusions.

Photo courtesy of And Miles to go Before I Sleep

Chen’s conviction doesn’t change the fact that there are still more than 80,000 undocumented migrant workers in Taiwan living under often hazardous and abusive conditions. Like the experts in the film say, major systemic changes are needed, but that has been slow to happen.

Regardless of whether discrimination played a role in the actions of the police, the ongoing debate over appropriate gun use among Taiwanese police officers is also worth exploring, especially after the killing of two officers last August. But that’s a topic for another documentary.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern