Soon after he was elected as a Conservative MP, Rory Stewart tried to sit down next to a party colleague.

“This seat is reserved,” the MP growled at him.

Stewart pointed out there was no “prayer card” in the brass holder at the back of the seat, meaning it was free. The unnamed Tory glowered.

“Why don’t you just fuck off,” he told Stewart.

Subsequently, piqued by Stewart’s election to the foreign affairs select committee, the same MP threatened to punch him on the nose.

DYSFUNCTIONAL GOVERNMENT

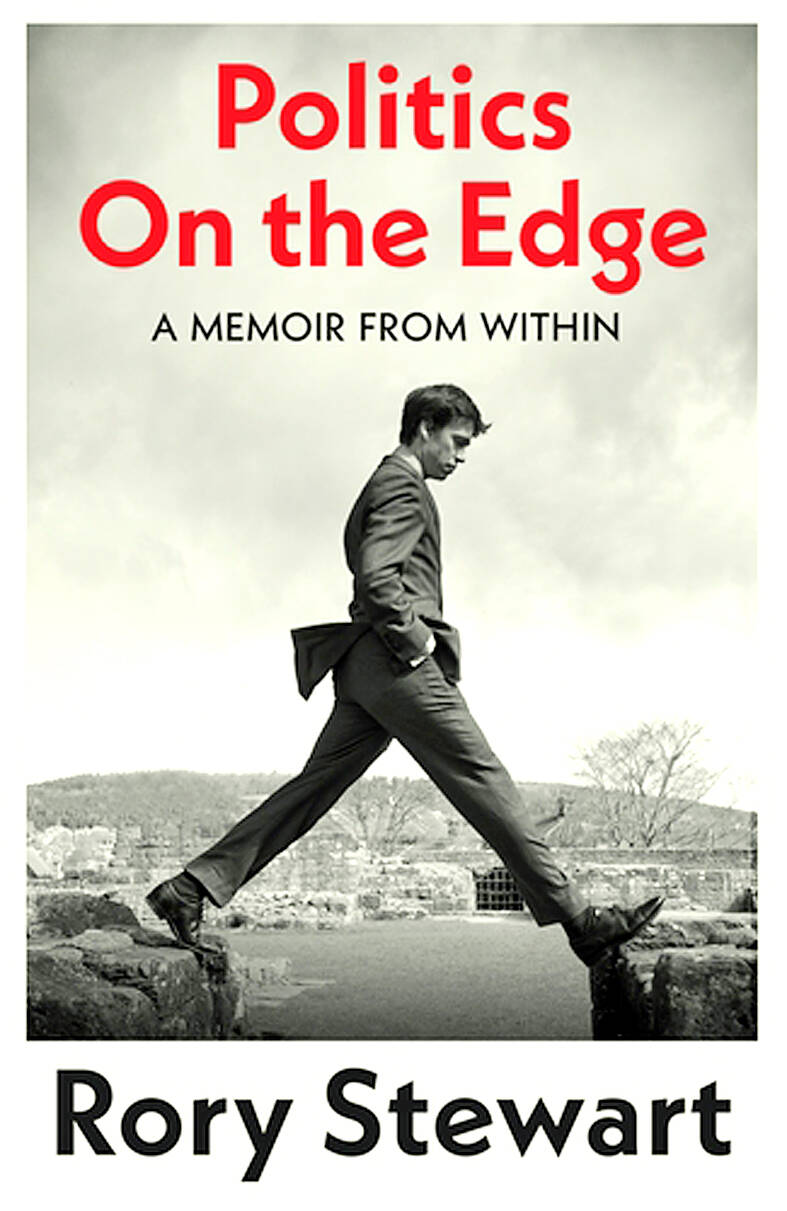

Stewart’s memoir of his nine years in British politics is filled with similarly grim and darkly amusing episodes. It is an excoriating account of a dysfunctional governing system. At every level — backbench MP, senior minister, permanent secretary — Stewart finds shallowness where there should be depth, vapidity instead of seriousness. His book is a brilliant insider portrait of a nation in decline, penned by an exasperated modern Boswell.

Educated at Eton, and the son of a British spook, Stewart governed an Iraqi province after the US-UK led invasion. He set up a charity in Kabul and took up a chair at Harvard. In 2009, filled with the idea of public service, he decided to stand for parliament. He was selected for the rural constituency of Penrith and the Border. The following year he was elected, a newbie politician with a closeup view of David Cameron’s coalition government.

Disillusionment was swift. MPs were uninterested in policy, he discovered. Instead they were obsessed with scandal. He found “impotence, suspicion, envy, resentment, claustrophobia and Schadenfreude.” Cameron made speeches about diversity. But he filled his private office with white-shirted old Etonians, drawn “from an unimaginably narrow social group.”

In one vote Stewart rebelled over an amendment on mountain rescue by hiding in the loo. No one noticed.

Stewart sympathized with some of the leadership’s causes, such as gay marriage and international development. In other respects, Cameron turned out to be a disappointment. Cabinet discussion was cursory. The prime minister was uninterested in Afghan strategy, and oblivious to looming populism. Stewart likens then chancellor George Osborne to an “18th-century cardinal,” “capable of breathtaking cynicism,” but also bright, engaged and self-mocking.

‘SHAMEFUL STATE’

In an author’s note, Stewart acknowledges that his former top colleagues will be angry with him for revealing their private conversations. He justifies this betrayal by citing the “shameful state” to which parliament has fallen — a “horrifying decline,” as he puts it, which can only be fixed by transparency. He omits the names of junior civil servants and a few backbenchers. Most are easily guessable, with the reader invited to play a game of spot-the-bastard.

All of which makes for a superbly readable book. After his unexpected 2015 election victory, Cameron made Stewart a junior environment minister, serving under Liz Truss. Truss prized “exaggerated simplicity” above “critical thinking,” “power and manipulation” over “truth and reason.” Stewart observes that this “new politics” offered “untethered hope” and “vagueness” instead of accuracy.

Truss was allergic to “caution and detail,” he adds.

Stewart is the author of three previous nonfiction works, including a bestselling travelogue, The Places in Between, about his journey through Afghanistan, part of a 6,000-mile solo walk across Asia. Here, he deploys his literary skills in the manner of a superior assassin. Truss is weird, Michael Gove silkily duplicitous, and Boris Johnson an “egotistical chancer.” Stewart recalls visiting Johnson in his foreign secretary’s lair — a red-cheeked figure whose eyes radiated “furtive cunning.”

He is kinder about Theresa May. After the Brexit vote and Cameron’s resignation, May made Stewart development minister, followed by prisons, and then promoted him to cabinet as secretary of state for international development. Unusually for a front-rank politician, she had a “private personality.” Stewart supported her EU withdrawal agreement, as hardline Brexiters plotted her overthrow, and the party lurched into magical thinking.

Stewart praises David Gauke, his justice secretary boss, as a person of moderation and decency. There was an “ironic, cavalier lift” to one of Gauke’s eyebrows. It hinted at a “warmth and irreverence unusual in our rickety political world,” Stewart writes. But the one-nation faction that both men represented failed to get its act together when May announced her departure. The Conservatives coalesced around Johnson. Sensible colleagues who despised him offered their endorsement.

SELF-CONTEMPT

The book has several moments of self-contempt.

At one point Stewart thought about killing himself. He brooded in the middle of the night and often experienced disgust. Politics, he came to think, was a “rebarbative profession.”

“In London, I felt increasingly exhausted and ashamed,” he admits. He developed migraines and kept going by taking painkillers. Despite all this, his idealism and love of country — his stated reason for joining the Tories — never quite left him.

Stewart relates his own doomed campaign to become Conservative party leader with brutal honesty. There were high points. He bypassed the rightwing pro-Johnson media by holding open meetings and walks — a strategy that saw his ratings rise with the public. He did well in the first Channel 4 debate. But in the next BBC encounter he bombed, crowded out by his more polished rivals. Exasperated, he took off his tie.

“I felt like a satellite falling out of orbit,” he records.

Along the way there were compensations. Stewart enjoyed being a constituency MP. He writes with lyrical fondness about Cumbria and its rustic voters. Surprisingly, he relished his time as prisons minister, managing to reduce drug and violence figures in 10 jails. He got better at politics, and at overcoming the inertia of civil servants. They tended to view ministers as ignorant and ephemeral and often spoke in corporate jargon. His warnings about Johnson — the politician and the man — were right.

It is hard to disagree with any of Stewart’s conclusions, about the dire state of our politics, and the strange and empty character of its representatives. I was left wondering if he would have had a less bruising time as a Labour MP. In 2019 Johnson purged leading remainers and Stewart quit both the Tories and his seat. Last year he reinvented himself as one half of a hugely successful current affairs podcast, The Rest Is Politics, co-hosted with Alastair Campbell.

After a memoir of such blistering frankness, there is no way the Conservative party will have Stewart back. Westminster is poorer without him, a wanderer turned prime minister manque. The world of ideas and letters is richer.

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislative caucus convener Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) and some in the deep blue camp seem determined to ensure many of the recall campaigns against their lawmakers succeed. Widely known as the “King of Hualien,” Fu also appears to have become the king of the KMT. In theory, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) outranks him, but Han is supposed to be even-handed in negotiations between party caucuses — the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) says he is not — and Fu has been outright ignoring Han. Party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) isn’t taking the lead on anything while Fu