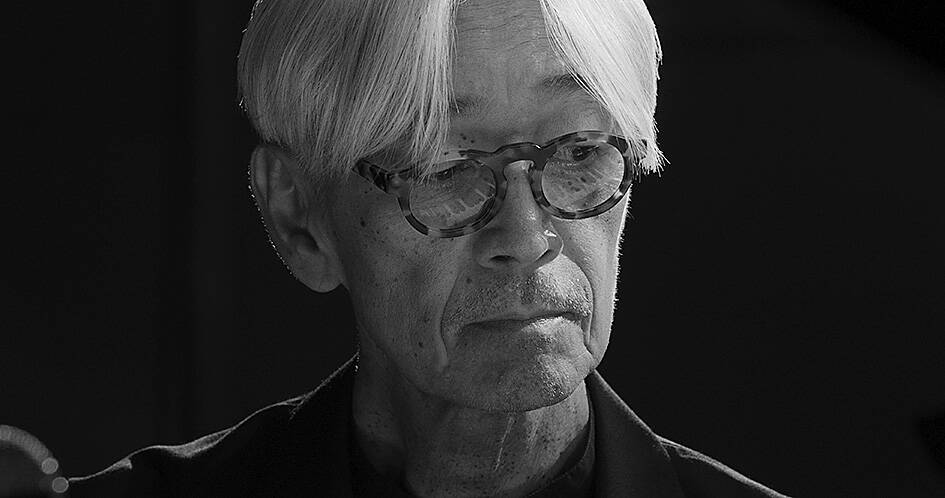

Sitting alone before a grand piano in a stark studio, Ryuichi Sakamoto takes the listener on a journey of his life, playing 20 of his compositions.

Shot entirely in black and white, on three 4K cameras, the film Opus, directed by Neo Sora, is the Japanese composer’s farewell, poetic yet bold, and deeply heartfelt.

Its world premiere is set for the Venice International Film Festival this month. The filming took place over several days, just a half year before his death on March 28 at 71.

Photo: AP

Sakamoto had been battling cancer since 2014, and could no longer do concert performances, and so he turned to film.

He plays pieces he had never performed on solo piano. He delivers a striking, new slow-tempo arrangement of Tong Poo, a composition from his early days with techno-pop Yellow Magic Orchestra that catapulted him to stardom in the late 1970s when Asian musicians still tended to be marginal in the West.

“I felt utterly hollow afterward, and my condition worsened for about a month,” Sakamoto says in a statement.

Photo: AP

He speaks only a few lines in the film.

“I need a break. This is tough. I’m pushing myself,” he says barely audibly in Japanese, about midway through the film.

He also says, “let’s go again,” indicating he wants to play a sequence again.

For the rest of the nearly two-hour film, he lets his piano do the talking.

The notes resonate from his fingers, lovingly shot in closeups, sometimes slowly, one pensive note at a time. Other times, they come jamming in those majestically Asian-evocative chords that have defined his sound.

After each piece, he lifts his hands up from the keys and holds them there in the air.

Opus is a testament to Sakamoto’s legendary filmography. He composed for some of the world’s greatest auteurs, including Bernardo Bertolucci, Brian DePalma, Takashi Miike, Alejandro Inarritu, Peter Kominsky and Nagisa Oshima.

The film is also evidence he remained active until the very end. He performs an excerpt from his meditative final album 12, released earlier this year.

By the time Sakamoto starts playing the melody from Bertolucci’s 1987 The Last Emperor, the emotions are almost overwhelming. The soundtrack, which also included musician David Byrne, won both an Oscar and a Grammy.

Sora, the director, who was raised in New York and Tokyo, says he and the crew were determined to capture the sense of time and timelessness, so crucial in Sakamoto’s art, in what everyone knew might be his final performance.

All the sounds that usually get taken out in post-production, rustling clothing, clicking nails or Sakamoto’s breathing, were purposely kept, not minimized in the mix.

“Part of the reason why we decided to shoot in black and white was because we thought that also highlighted the physicality of his body, with the black and white keys of the piano,” said Sora, named one of the 25 New Faces of Independent Film by Filmmaker Magazine in 2020.

Sakamoto first came up with a set list, and the filmmakers worked out with him in advance a detailed plan for a visual narrative and concept.

Designed as a film from the get-go, not just a documentary of a performance, the work features the lighting design, artful long takes and Zoom-lens closeups concocted by Bill Kirstein, the director of photography.

“We were able to get shots of hands and keys that we were never able to get before,” said Kirstein, comparing the film’s imagery to a drawing.

Hundreds of pounds of weights were laid on the floor so the camera dolly could move silently without creaking.

A memorable moment comes toward the end when Sakamoto plays Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, from the 1983 Oshima film bearing the same title and starring David Bowie and Golden Lion-winner Takeshi Kitano.

Sakamoto also acted in the film, portraying a World War II Japanese soldier who commands a prisoner-of-war camp. He was young, barely in his 30s. Yet in so many ways he remained unchanged as that frail silver-haired bespectacled man, crouched over his piano.

As the film moves to the final tune, Sakamoto has disappeared, gone to that other world that some call heaven. The piano, under a spotlight, is playing on its own, a reminder his music is eternal, and still here.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on