The Tory xenophobes who police our coasts should watch their words. The so-called English language is actually a multicultural hubbub, jumbling together classical derivations, Anglo-Saxon roots, local dialect, fancy continental imports and souvenirs of further-flung territories: the innocuous term “breeze,” for instance, is borrowed from Portuguese colonists in India, who used it to define a cooling afternoon wind in the tropics. English is happily borderless, and the same is true of the Oxford English Dictionary which, as Sarah Ogilvie says, set out in the mid-19th century to trace words back to “their natural habitat,” wherever that may be.

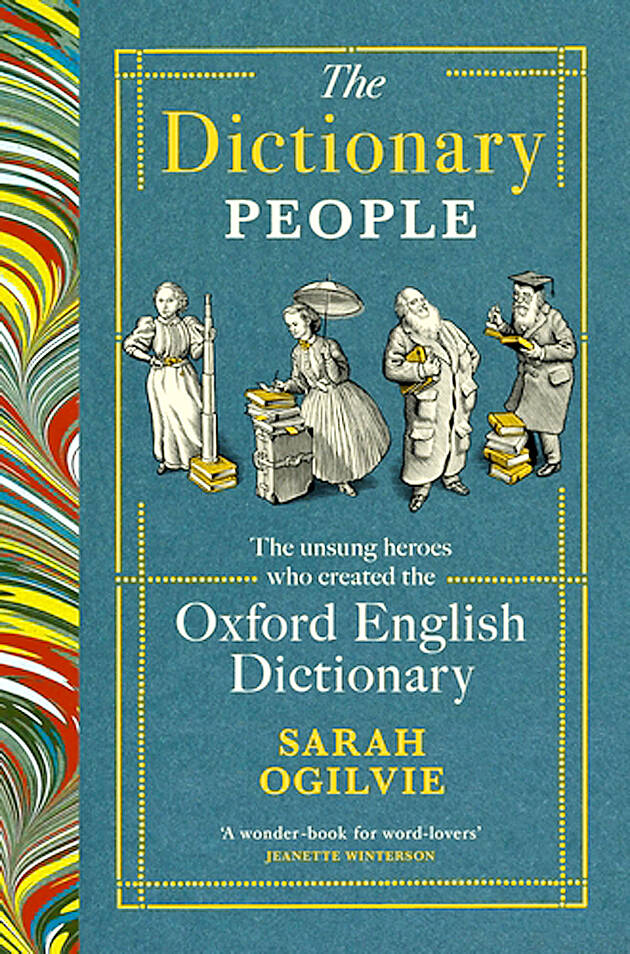

Officially, the first headquarters of the OED was an iron shed in a north Oxford garden, grandly designated a “scriptorium” by the lexicographers who toiled inside it, often solemnly costumed in academic gowns and mortar boards. But from the beginning this was a crowdsourced project, and Ogilvie, tracking down leads from an address book kept by one of the earliest editors, has unearthed hundreds of anonymous volunteers on all five continents who collected recondite words or trawled unreadable books for illustrative quotations.

LURID CHARACTERS

A few of Ogilvie’s dictionary people are lurid characters: she identifies three murderers, one cannibal and several institutionalized lunatics. Noting that “overeducation” was the official reason for confining one unfortunate woman in 1895, she wonders whether the OED can be held responsible for the diagnosis of madness; on reflection she admits that the habit of reading not for overall meaning but to pick out single words suits “quite a few of us who are neurodiverse, or who present on the autism spectrum.”

Google nowadays searches texts in the same way, but there is no standard of sanity for electronic brains. Mostly, however, Ogilvie’s obsessives are harmless academics, hoarders of arcane information that passes for knowledge. She visits one Oxford household whose occupants have to sleep in the kitchen because everywhere else is stuffed with papers.

Another dotty boffin perambulates in a coat whose 28 pockets store letters, books and philological offprints along with a clanking armory of nail clippers, a knife-sharpener and a corkscrew, not to mention a scone that he carries for emergencies.

Ogilvie concludes with a touching diptych in honor of two very different devotees, both proudly self-taught. In 1915, James Murray, a draper’s son who was snubbed by collegiate Oxford during his decades editing the OED, composes his own envoi . After elegiacally deciding on a definition for twilight, he puts down his pen, removes his scholar’s cap, takes to his bed with pleurisy and promptly dies, his mission complete.

Then in 2006, on a return trip to her native Australia, Ogilvie meets Chris Collier, who over the course of 35 years sent the dictionary 100,000 quotations from a Brisbane tabloid, all carefully cut and pasted in what he called his office, which was a park behind a pub; he posted them to Oxford wrapped in cereal packets with a residue of crumbled cornflakes and tufts of dog hair.

Having reconstructed the lives of countless defunct dictionary people, Ogilvie at last meets one of these “unsung heroes” in the flesh — though she is grateful that Collier, an unkempt naturist who was renowned locally for mowing his lawn stark naked, squeezes himself into “a pair of very short shorts” before she arrives.

QUIRKY LANGUAGE

Eccentric as Ogilvie’s people often are, the language they grapple with is even quirkier and kinkier, and its oddities enliven her book. I’m sad that I’ll probably never have a chance to use the verb absquatulate, which means to abscond. But words are not only for nerds: they can have an erotic charge, and one Victorian reader who specialized in the vocabulary of flagellation amassed a collection of porn so bulky that he needed a purpose-built bachelor pad at Gray’s Inn to house it. Potent without being aphrodisiac, other words serve as magic spells. Pharmacy, I was delighted to learn, originally referred to potions used in divination or witchcraft.

Some etymologies are hopelessly irregular. Condom, defined as “a contrivance used by fornicators,” caused problems that were geographical as well as moral. The reader who proposed it in the 1880s assumed, since “everything obscene comes from France,” that it was named after a French town called Quondam; he packaged his submission in its own equivalent of a french letter, marked “PRIVATE” and sealed in a separate envelope with a note warning that the word should probably be left out of the dictionary, which it was.

Suffragists — not suffragettes, which is diminutive and therefore condescending — took their name from a Middle English term for intercessory prayers. Although the word has nothing to do with suffering, the fortuitous echo lent an aura of martyrdom to Emmeline Pankhurst’s followers when they were force-fed during their hunger strikes in prison.

English, like the communities in which it circulates, remains a gloriously impure mess, and all the OED can do is impose alphabetical order. Ogilvie dismisses 19th-century schemes to invent an artificial language, variously called Spelin, Spokil or Mundolingue. The best known of these ideal projects is Esperanto, which remains merely aspirational: the word means “the hopeful one.” But we hope in vain for a universal idiom that will pacify the world, and what we have instead is the differently accented versions of English in which we speak, shout, argue and sometimes sing, using words that continue to proliferate, accumulate new meanings and tantalize would-be definers. We like to think that language is our creation; the truth is that it created us, and we are its babbling mouthpiece.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the