A group of Uyghur friends are having a late-night chat. “I wish the Chinese would just conquer the world,” one says suddenly. “Why do you say that?” another asks, surprised. “The world doesn’t care what happens to us,” the first man replies. “Since we can’t have freedom anyway, let the whole world taste subjugation. Then we would all be the same. We wouldn’t be alone in our suffering.”

It is an understandable outburst of bitterness. The Uyghurs are a Muslim minority who live mainly in China’s north-western Xinjiang region. They have long faced discrimination and persecution. Since 2016, the repression has greatly intensified, with mass detention, forced sterilization and abortion, the separation of thousands of children from their parents, and the razing of thousands of mosques. Yet support for Uighurs has been equivocal, not least from Muslim-majority countries, many of which are outraged by the burning of a Koran in Sweden but remain silent about the detention of more than 1 million Uighurs in Xinjiang, for fear of upsetting Beijing.

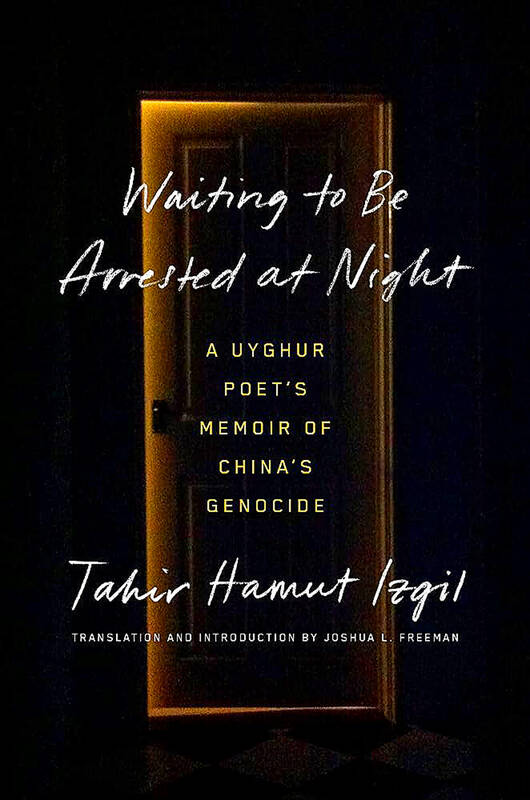

Tahir Hamut Izgil’s Waiting to Be Arrested at Night, which recounts that conversation, is not, however, a bitter book. It is suffused, rather, by a deep sense of sadness, and of despondency even amid hope.

“Yet our words could undo nothing here,/even the things we brought to be,” as one of Izgil’s poems laments.

A poet and film-maker, Izgil is famed for bringing a modernist sensibility to Uighur poetry. He did not set out to be a political activist. The very fact of being a Uighur, though, in a country that seeks to erase Uighur existence, both culturally and physically, turns everyday life into a political act. And for a poet living in a culture within which “verse is woven into daily life,” writing is necessarily also an act of witness and of resistance.

Despite the subtitle of the book — “A Uyghur Poet’s Memoir of China’s Genocide” — there are no depictions here of genocide, or of torture, or even of violence. We know all these things are happening, but off-page. Izgil’s memoir is a story about how to survive in, and to negotiate one’s way through, a society in which repression has become routine, and the power of the state is unfettered. The book’s restraint is also its strength. The tension in the narrative flows from the dread captured in the title — the dread of waiting to be arrested, to be vanished into detention, a dread no Uighur can escape.

Beijing’s strategy has been, over the past decade, to cut Uighurs off from the rest of the world and from one another, too. When censorship and surveillance made it impossible to link to the Internet beyond the Chinese firewall, many Uighurs took to keeping in touch with the outside world through shortwave radios. Until, that is, the government banned the sale of such radios and organized mass raids into people’s homes to confiscate them.

“We suddenly found ourselves living like frogs at the bottom of a well,” Izgil observes.

Beijing seeks to cut off Uighurs from their past and their traditions, too. Qur’ans are seized and history books banned, including many previously authorized by the state. Even personal names become part of the assault on Uighur culture. Beijing’s list of prohibited names tells Uighurs what they cannot call their children. Some names are apparently too “Muslim” — Aisha, Fatima, Saifuddin; others, such as Arafat, too political. When the list was first introduced, newspapers carried announcements such as: “My son’s birth name was Arafat Ablikim. From now on he will be known as Bekhtiyar Ablikim.”

The greatest dread is of the physical repression wreaked upon Uighurs: mass detentions, torture, violence. We get a glimpse of the horror when Izgil and his wife, Marhaba, attend a police station to have their biometric details collected — fingerprints, blood samples, facial scans. Along a basement corridor, they see a cell fitted out with iron restraints and a notorious “tiger chair,” used to force detainees into agonizing stress positions. On the floor are bloodstains.

People start disappearing, first in small numbers, eventually up to 1 million. They are taken to “study centres” — the code for mass detention camps — though nobody knows which one.

“They simply vanished,” Izgil writes.

The police knocked on the door when “your name was on the list.” There was, though, “no way to know if or when your name would show up on the list. We all lived within this frightening uncertainty.” It spawned a climate in which people feared one another as much as they feared the authorities.

Eventually, Tahir and Marhaba realize that their only option is to leave China. Emigration, though, is fiendishly difficult, especially for Uighurs, whose passports are held by the authorities. Somehow, they manage to negotiate the hurdles — though only after bribing doctors to certify one of their daughters as suffering from a form of epilepsy that has to be treated abroad. They escape to America to claim political asylum.

Relief at escape from tyranny is interwoven with the anguish of exile and of survivor’s guilt: “While we know the joy of those lucky few who boarded Noah’s ark, we live with the coward’s shame hidden in that word ‘escape.’” There is a sense of bleakness that bursts out in What Is It, Izgil’s first poem written after his escape to America: “These days/are crowded with shattered horizons,/shattered!” It is the pain of knowing that too many remain crushed by tyranny.

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions

In the run-up to World War II, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence service, began to fear that Hitler would launch a war Germany could not win. Deeply disappointed by the sell-out of the Munich Agreement in 1938, Canaris conducted several clandestine operations that were aimed at getting the UK to wake up, invest in defense and actively support the nations Hitler planned to invade. For example, the “Dutch war scare” of January 1939 saw fake intelligence leaked to the British that suggested that Germany was planning to invade the Netherlands in February and acquire airfields

The launch of DeepSeek-R1 AI by Hangzhou-based High-Flyer and subsequent impact reveals a lot about the state of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) today, both good and bad. It touches on the state of Chinese technology, innovation, intellectual property theft, sanctions busting smuggling, propaganda, geopolitics and as with everything in China, the power politics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). PLEASING XI JINPING DeepSeek’s creation is almost certainly no accident. In 2015 CCP Secretary General Xi Jinping (習近平) launched his Made in China 2025 program intended to move China away from low-end manufacturing into an innovative technological powerhouse, with Artificial Intelligence