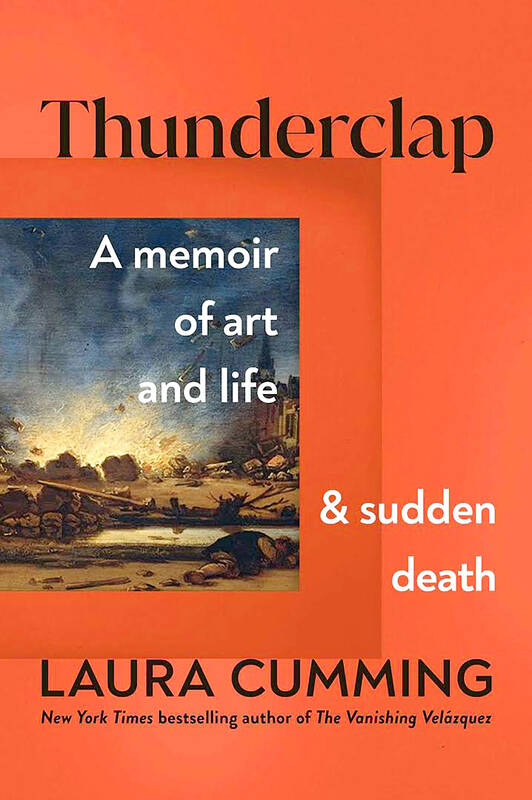

For Laura Cumming, Dutch art is a placid paradise with the countdown to a cataclysm ticking away in the background. The immaculately swept streets and waxed floors in the paintings, the thin ice that supports a crowd of skaters in a frozen winter, the churches that are containers for mellow light and silence — all are instantly annihilated by the big bang of the book’s title.

The Delft Thunderclap in 1654 was the detonation of 40 tonnes of gunpowder, stored for the city’s defence in the cellar of a former convent and probably set alight by a spark when a guard turned his key in a rusty lock or swung his lantern carelessly. Buildings imploded, and numberless people were crushed by the rubble. As if still reeling from an aftershock, Cumming is left trying to balance the safety or sanctity of art against the accidental violence of life, both on that day in the 17th century and in her personal experience of rupture and irreparable loss.

Among those killed by the thunderclap was Carel Fabritius, the painter whose eerily calm A View of Delft in the National Gallery steadied Cumming during her “volatile and confused” early days in London.

The book begins with her declaration of love for the painting, which she remembers visiting almost daily before she drifted off to trysts with someone she admits she did not love. Her actual boyfriend paled before Fabritius’s “darkly handsome” musician, who lolls beside his lute and viol, and Cumming wished herself out of clamorous, chaotic London into serenely empty Delft.

Dutch art still consoles her by holding out the hope of “a perfectible world.” During the nervy COVID lockdowns, she kept a reproduction of Vermeer’s The Little Street pinned to a wall beside her desk as a pacifier. The apertures in Vermeer’s gabled facade invited her into “a next-door microcosm for the mind and eye,” subduing her to a stillness like that of the figure in the painting who sits hunched over some needlework inside her house.

The images Cumming studies so raptly stop time, in an “optical act” that works like hypnosis. The water in Jan van Goyen’s landscapes forgets to flow, and clouds pause above their reflections in the mirrored surface of a river. That reverie turns beatific in Vermeer’s View of Delft, where Cumming calls the stepped roofs of the houses “stairways to heaven;” even more mystically, she says that the bucket carried by a maid in a painting by Pieter de Hooch is “blessed by the sunlight.”

This kind of appreciative attention slows down the flickery eye and extends its range, and as Cumming maintains her vigil she sees beyond the moment framed on the wall and glimpses a kind of eternity. The hat of a brewer in a Frans Hals portrait becomes “so large it has its own planetary halo,” while some peaches painted by Adriaen Coorte are “side-lit in deep darkness like two phases of the moon in outer space.”

In a detour, Cumming discusses the paranormal phenomenon known in the Outer Hebrides as second sight. During his time in the 1940s in a croft on the Isle of Lewis, her father, James Cumming, painted one of these prophets, a misty figure with a witch’s adder stone as his extra eye. Cumming has her own verbal equivalent to the seer’s visionary gift. Described by her, a group of prickly shells in a still life by Coorte performs a stationary ballet, and she even elicits music from the mouth of a pearly conch in the group.

“The eye sees,” she says in an enchanted hush, “and it hears.”

Such magical charms fail to muffle the thunderclap, which resonates ominously throughout the book. Cumming pictures the “mushroom cloud” of dust it produced, then compares it to the collapse of the World Trade Center and to the unsafe cargo of ammonium nitrate that tore apart the Beirut port in 2020.

With silent stealth, the explosion recurs in a sunburst that rendered Cumming’s daughter instantaneously colourblind, and in the unseen growth of a tumour that killed her father. But the blast is also defused and startlingly diverted into a series of aesthetic epiphanies. To compensate for the thunder, Cumming finds a “lightning strike of geometry, symmetry and sheer verticality” in an avenue of alder trees by Hobbema.

Another “lightning flash” of yellow shines from a bird’s wing painted by Fabritius, and she is dazzled by Vermeer’s “pinpricks of luminous paint that crackle and glow”.

Yet Cumming keeps helplessly circling back to the stark clash between art’s composure and the catastrophe of the thunderclap, never entirely satisfied by her own quest for a “redemptive grace” that is dispensed by light and by the brushstrokes of painters. Then, on the final page, as she gazes at Fabritius’s The Goldfinch — his most tender and painful image, in which the tethered bird hops as near the end of its perch as its chain will allow — she resolves the dispute in a small miracle of perception. Her eye, probing the surface, uncovers ballistic evidence that explains why this fragile picture survived when Fabritius’s house collapsed on it.

I won’t spoil the deductive climax, except to say it gives off a brilliant flash of imaginative ignition as the book’s two opposed ideas electrically connect. When I read Cumming’s last paragraph, the baleful rumble of the Delft disaster became an outburst of delighted, admiring laughter.

On Jan. 17, Beijing announced that it would allow residents of Shanghai and Fujian Province to visit Taiwan. The two sides are still working out the details. President William Lai (賴清德) has been promoting cross-strait tourism, perhaps to soften the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) attitudes, perhaps as a sop to international and local opinion leaders. Likely the latter, since many observers understand that the twin drivers of cross-strait tourism — the belief that Chinese tourists will bring money into Taiwan, and the belief that tourism will create better relations — are both false. CHINESE TOURISM PIPE DREAM Back in July

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

Could Taiwan’s democracy be at risk? There is a lot of apocalyptic commentary right now suggesting that this is the case, but it is always a conspiracy by the other guys — our side is firmly on the side of protecting democracy and always has been, unlike them! The situation is nowhere near that bleak — yet. The concern is that the power struggle between the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and their now effectively pan-blue allies the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) intensifies to the point where democratic functions start to break down. Both

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in