I well remember from over 10 years ago, a man of around 30 walking into my Taipei apartment with three books he’d like considered for review in the Taipei Times.

It transpired he was a Canadian professor of literature teaching in the National Central University in Chungli. We got talking, and he indeed had an extraordinary tale to tell, of drunken orgies, fights and at least one death. His area, he said, was nothing like well-mannered Taipei. The Taipei Times eventually ran my conversation with him as an interview with “a professor with a fighting chance.”

The books proved fascinating, but very strange. I reviewed two of them, and others were to follow. I decided he was talented but eccentric and called him Taiwan’s Samuel Beckett.

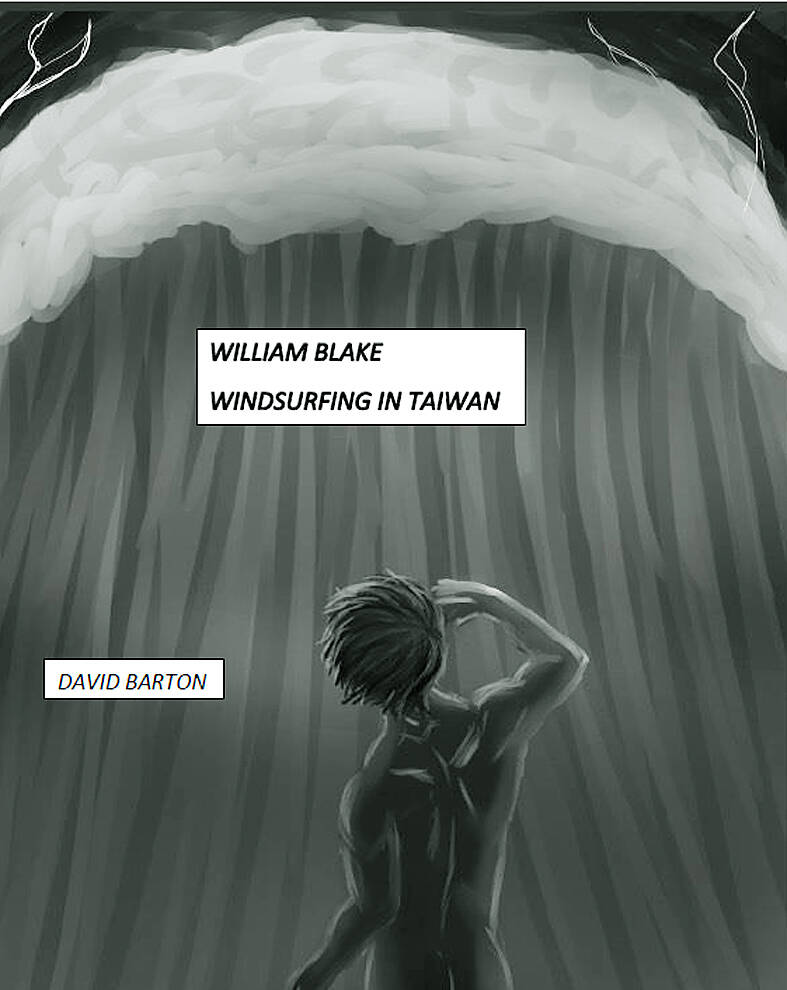

His name is David Barton and he has now come up with another book, this time based on the “prophetic books” of the English Romantic poet William Blake. These are works that have baffled even the most erudite Blake scholars, so much so that they are frequently omitted from accounts of the poet. They can be seen under the titles Jerusalem, Milton, The Four Zoas, and more.

The poet John Milton, incidentally, was something of a hero in the Romantic era in which Blake lived — a champion of free speech and of republicanism. Blake’s own views were paradoxical by any standards, opposing 18th century rationalism (“the Enlightenment”) and a believer in a Christianity of a very unusual kind.

Barton’s book begins with windsurfing in Guanyin on Taiwan’s northwest coast, and elaborate references to the 50 pages of illustrated text of Milton and the 100 pages of Jerusalem. People are seen as having been taken over by a scientific objectivity, whereas Blake preferred a world dominated by angels (“elohim”).

“When the sun rises, do you not see a round disc of fire, somewhat like a guinea?” “No! No!” replies Blake. “I see an innumerable company of the heavenly host crying ‘Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God almighty.”

Blake was considered mad, and that he wasn’t locked up was largely due, writes Barton, to the intercession of uncomprehending friends.

This is a wonderful idea for a book, combining the wild loneliness of windsurfing and the one-of-a-kind eccentricity of William Blake.

“Blake is a windsurfer of this oldest Chaos, the Ocean, as was his teacher, John Milton” writes Barton. “For Taiwan, China is that spectral illusion, Satanic and looming. Grotesque Giant or Snake looking for its Taiwan to swallow.”

Unfortunately, the Taiwan Strait (the ‘Black Strait’) is now brown and nearly dead. Blake windsurfs in a nasty chemical wash, a toilet bowl of toxic mud where one avoids a razor-sharp dead reef that shows its teeth at low tide.”

Barton in fact creates his own Guanyin mythology, complete with a contempt for reason, plus the Ocean and the Big Bang 14 billion years ago.

This is undoubtedly Barton’s best book. Teaching Inghelish in Taiwan (2001) was funny, and Saskatchewan (2010) had its own special atmosphere. But this new book has the huge advantage of combining two apparently irreconcilable subjects, to magnificent effect.

This is not to say I understand it all. But the same could be said of Blake’s prophetic books, though not of Milton.

“I was brought to windsurfing in Taiwan by the wreckage and chaos of a previous life, my first 15 years in Taiwan, a professor of 17th and 18th century literature and a bar owner.”

This being Barton, there’s a wide range of literary references, combined with doodles and abstract or impressionist paintings. There are also aphorisms galore — the ocean as a raging alcoholic, Nietzsche showing the way to Lao Tze, Blake’s Fleas that suck the life out of the Fly (and windsurfers), Rumpelstiltskin and a riddle in chemicals, copper and ink.

Meanwhile Barton is plagued by a giant wolf spider, “about hand size,” when four-meter waves keep him from windsurfing. But Los, one of Blake’s heroes, will be out there whatever the weather.

Barton follows in the tradition of seeing Milton as of the Devil’s party without knowing it: “Milton’s City in Hell, Pandemonium, is far more believable than anything the great poet could imagine in Heaven.”

Los was, in Blake, the embodiment of inspiration and creativity, whereas Urizen was reason and, hence, science and industrialism.

The view that Milton’s God was a bully was adopted by the great critic William Empson in Milton’s God (1961).

Barton doesn’t lay out his Blakean world in any formal way. Instead, you have to piece it together from Barton’s impressionistic fragments, often inspired though they are. “Tell me that Blake isn’t Darwinian,” Barton writes. “But funnier.”

In some ways this book is an anthology of fragments from some of Barton’s favourite creative intellects — Wallace Stevens, Iggy Pop, Bob Marley, Monty Python, Alexander Pope, David Lynch, Jimmy Hendrix and Charlie Parker.

A word needs to be said about the illustrations. Some squiggles, other photographs of the shoreline, or of monstrosities such as the Linko Power Station, coal-fired and “a massive beast.”

It appears Barton was given a year’s university sabbatical to write this book. Don’t read it if you want to understand all of Blake or all of Barton, though some information can be gleaned. Both authors could be considered a little mad on an uncharitable view. But as Barton puts it, “which of Blake’s Visions is not a pathological hallucination?”

Barton is a cultural guru to his fingertips, though he aspires to be something else as well.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the