July 10 to July 16

Not even the construction of fortified stone walls in 1826 could convince Fongshan County (鳳山) administrators to move back to the old government seat of Singlong Village (興隆莊).

They had been working from the more prosperous and convenient settlement of Pitou Street (埤頭), about 10km away, and seemingly had little interest in returning, writes Tu Chien-feng (杜劍鋒) in Nostalgia for the 180-year-old Old Fongshan City (鳳山縣舊城建城180年懷舊).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The economic disparity between the two towns only widened over the years, and by 1847 Singlong’s population had dwindled to about 500 households while Pitou had more than 8,000. And the officials were still working out of Pitou, which was only protected by a fence of sharp bamboo sticks.

As a result, the fortified Singlong Village — now known as Old Fongshan City (鳳山舊城) in today’s Zuoying District (左營) in Kaohsiung, was never really used for its true purposes, although near the coast, it did have military value. Old Fongshan City holds the title of Taiwan’s first walled village as an earthen wall was built around it in 1721 due to local unrest, but stone fortifications were forbidden by Qing rulers until the 1820s. Pitou’s (New Fongshan City) walls weren’t erected until 1854.

Old Fongshan City was just far enough out of the way to avoid the destruction of its walls by the Japanese, and three of its four gates remain. After World War II, part of it became a military base, while the rest of it was at one point occupied by more than 100,000 refugees from China in makeshift structures. Little attention was paid to protecting it until 1988, when it was declared a first class historic site. Today, it’s one of the best preserved walled cities in Taiwan and a tourist attraction. (see ‘Taiwan’s first walled city, then and now,’ May 14, 2021 for travel details).

Photo courtesy of Open Museum

FIRST WALLED VILLAGE

The Qing established Fongshan County in 1684, and around 1694 designated Singlong Village as its administrative seat. It was chosen for strategic and transportation purposes as it was near the ocean and flanked by Turtle and Snake mountains. Prospects for further development and agricultural expansion were due to the lack of flat land, and over the years the center of commerce for the region was at Pitou Street.

Old Fongshan City grew quickly, and within 10 years of its designation it boasted most of the facilities, temples and buildings needed for a county seat. Like many towns during that time, it was fortified with a fence of sharpened bamboo and thorny vines.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Qing forbid Taiwanese from building walled villages, citing earthquakes, lack of money and the fear that these cities would become a hotbed for pirates and bandits who would threaten the southeast coast of China.

However, as the Han settlers increased and spread out to find arable land, so did their conflicts with indigenous groups and bandits. The settlers petitioned the Qing to let them build stone walls around their settlements, but were refused.

Old Fongshan City was captured during the 1721 uprising led by “Duck King” Chu Yi-kuei (朱一貴), finally changing the Qing’s attitude. In 1722, construction of the earth walls began. Wooden fences were also allowed around that time, but stone walls were still forbidden. In 1734, three layers of sharp bamboo fences were added outside the walls along with four cannons.

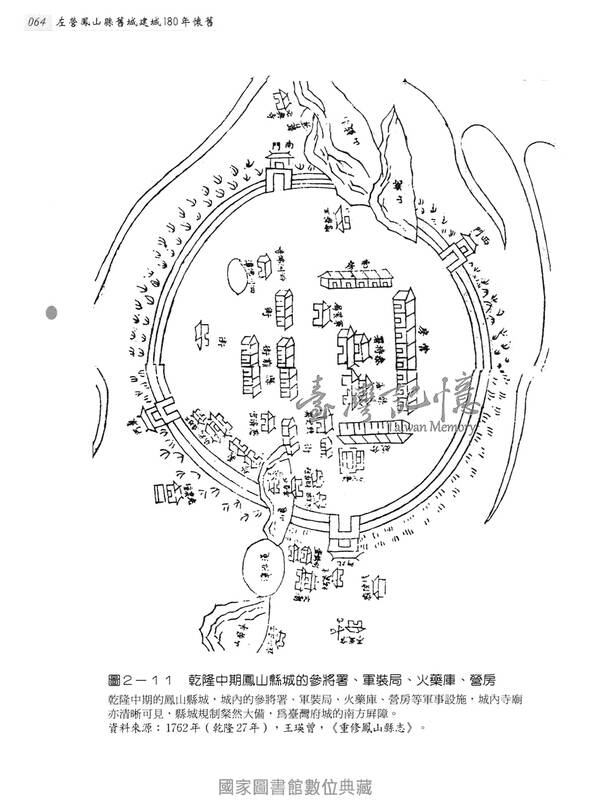

Photo courtesy of National central Library

There were already requests to move the county seat to Pitou then, but Lan Ting-yuan (藍鼎元), who came to help pacify the rebellion, argued that Old Fongshan City was a more strategic and vital location that should be fortified even more. Lan suggested the use of stone walls, but was ignored.

STONE WALL DILEMMA

However it seemed that these defenses were not enough, as the city was again taken during the Lin Shuang-wen (林爽文) rebellion of 1787-1788, the largest under the Qing. Most “fortified” towns in the area fell within the first two months of the unrest.

Photo courtesy of Open Museum

In 1787, the Qianlong Emperor decreed that stone walls would be allowed after the quelling of the uprising, acknowledging the deficiencies of bamboo and earthen walls. However, once the war was over, he changed his mind, only allowing stone walls for Chiayi and Tainan due to budget concerns.

Qing general Fukanggan stayed in Taiwan to oversee the reconstruction and assessed Fongshan’s situation. He proposed that the administrative seat be moved to Pitou, while keeping Old Fongshan City as a military fortress. It was inevitable as Pitou was much more bustling and better connected to the rest of Fongshan’s communities, and it was also inconvenient for officials to run back and forth between the two locales. The move was made official in 1788.

Pirates led by Tsai Chien (蔡牽) ravaged the area in 1805, sacking Pitou and killing the magistrate. Instead of rebuilding Pitou, officials suggested moving the administrative seat back to the strategically defensive Singlong and building a stone wall around it.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

However, officials continued working from Pitou because they felt that Singlong wouldn’t be safe without stone walls. After another attack on Pitou in 1823, the government and local elite raised enough funds to start building the walls, completing them in 1826.

This wall was poorly planned, as it included Turtle Mountain within its enclosure, causing frequent flooding within the city. Few people wanted to settle there, and plans for it to become a county seat were officially scrapped in 1847. As such, the monumental stone city was “reduced to a tiny military stronghold in the northwest corner of the Kaohsiung Plain,” Tu writes.

Locals blamed the downfall to fengshui — by caging the turtle, the area’s fate was sealed. However, a few settlements nearby on the main road to Tainan remained prosperous, especially with the opening of Kaohsiung to foreign trade in 1863.

DECAY AND RESTORATION

Unmantained, the walled city weathered the elements and vandalism but because of its remote location it survived the dismantling of city walls by the Japanese in other towns. However, parts of it were still demolished in the 1920s and 1930s to make way for roads and a train station, and in 1939 the west gate and the adjacent wall were torn down for a military base. The east gate was in pretty bad shape by the end of the Japanese era.

Military dependent settlements sprung up in the area after the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) arrived, at one point more than 100,000 people lived in crude bamboo and clay dwellings within the walls. As Zuoying became an important industrial area in the 1970s, new roads were built through and around the old city, completely changing the landscape.

Fortunately, the remaining three gates still stood, although buried in concrete and metal structures. The first act to protect them was in 1961 — since the north gate was still occupied by squatters and the east gate was inside a military base, the city built a roundabout around the south gate and protected it from traffic with a metal fence.

A 1980 report shows that only the walls around the east gate were intact. Taiwan passed its cultural protection law in 1982, and the old city was listed as a first-grade historic relic in 1985. Renovations began in 1988 and were completed in 1993.

While the government recovered the plaque of the demolished west gate, there was no indication where exactly it once stood. Kuo Chi-ching (郭吉清), a teacher at nearby Haiqing Vocational High School spent over a decade trying to solve the mystery, finally in 2001 discovering a 1933 map that showed the four gates while preparing an exhibition for the Kaohsiung Museum of History.

Because the landscape had totally changed, he had to cross-check maps from various eras, matching them one by one until he found a possible site. After years of painstaking work, they finally determined the location, revealing the news in a special exhibition in October 2004.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

In recent weeks the Trump Administration has been demanding that Taiwan transfer half of its chip manufacturing to the US. In an interview with NewsNation, US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick said that the US would need 50 percent of domestic chip production to protect Taiwan. He stated, discussing Taiwan’s chip production: “My argument to them was, well, if you have 95 percent, how am I gonna get it to protect you? You’re going to put it on a plane? You’re going to put it on a boat?” The stench of the Trump Administration’s mafia-style notions of “protection” was strong

Every now and then, it’s nice to just point somewhere on a map and head out with no plan. In Taiwan, where convenience reigns, food options are plentiful and people are generally friendly and helpful, this type of trip is that much easier to pull off. One day last November, a spur-of-the-moment day hike in the hills of Chiayi County turned into a surprisingly memorable experience that impressed on me once again how fortunate we all are to call this island home. The scenery I walked through that day — a mix of forest and farms reaching up into the clouds

With one week left until election day, the drama is high in the race for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair. The race is still potentially wide open between the three frontrunners. The most accurate poll is done by Apollo Survey & Research Co (艾普羅民調公司), which was conducted a week and a half ago with two-thirds of the respondents party members, who are the only ones eligible to vote. For details on the candidates, check the Oct. 4 edition of this column, “A look at the KMT chair candidates” on page 12. The popular frontrunner was 56-year-old Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文)

“How China Threatens to Force Taiwan Into a Total Blackout” screamed a Wall Street Journal (WSJ) headline last week, yet another of the endless clickbait examples of the energy threat via blockade that doesn’t exist. Since the headline is recycled, I will recycle the rebuttal: once industrial power demand collapses (there’s a blockade so trade is gone, remember?) “a handful of shops and factories could run for months on coal and renewables, as Ko Yun-ling (柯昀伶) and Chao Chia-wei (趙家緯) pointed out in a piece at Taiwan Insight earlier this year.” Sadly, the existence of these facts will not stop the