June 19 to June 25

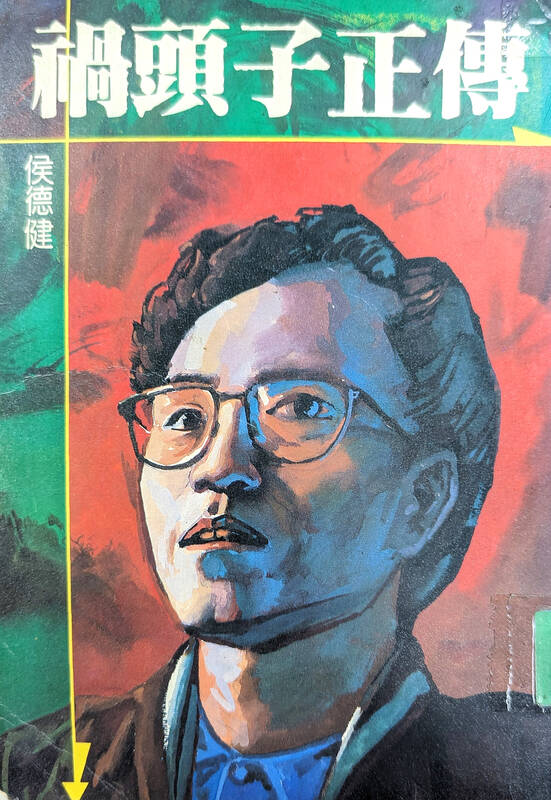

The nation was shocked when promising songwriter Hou Dejian (侯德健) illegally moved to Beijing in 1983. Hou was allegedly unhappy that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was trying to alter his lyrics and pressure him to write propaganda songs, but he writes in his autobiography, True Story of a Troublemaker (禍頭子正傳), that he really just wanted to see the place where his parents were born, and felt that he would find more creative inspiration there. His family, including his wife and young son, didn’t know about his plans.

“I felt like I couldn’t find satisfaction or surpass myself in Taiwan’s music scene,” he said in October 1988 during his first interview with the Taiwanese media since his departure. “I wanted to discover a new path.”

Photo courtesy of Taipei Public Library

Hou had his ups and downs in China, but he managed to release two acclaimed albums and was invited to perform in the 1989 CCTV New Year’s Gala. Things were finally looking up, he told the media.

But less than a year later, Hou found himself as one of the “Four Gentlemen (四君子) of Tiananmen Square” who led a hunger strike during the final days of the student demonstrations. He was eventually deported (or in his words, half-coerced and half-tricked by the authorities into smuggling himself) back to Taiwan.

His return on June 20, 1990, was just as unexpected as his departure. After paying a fine for illegal entry, he released his autobiography and an album before emigrating to New Zealand, saying that he felt unwelcome in Taiwan due to negative media attention.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Most Taiwanese are probably familiar with at least one of the few hits Hou penned before taking his talents to China, especially Any Empty Bottles for Sale? (酒矸倘賣無) sung by Su Rui (蘇芮).

ETERNAL GUEST

Hou grew up in a military dependents village in Kaohsiung’s Gangshan District (岡山) to parents from Sichuan and Hunan provinces. He writes that he felt like a guest no matter where he went.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute

“When people asked about my background, I always said I’m Sichuanese. But when they asked where my home was, I said without hesitation, Chiyuan Village (致遠) in Gangshan,” he writes, adding that he never felt any contradiction between the two.

Attending school with mostly Taiwanese kids, he writes that although there was discrimination, he mostly got along with them and was one of the few Mainlander students fluent in Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese). But he felt deeply hurt during one incident while visiting a friend in Kaohsiung. After enjoying a fun afternoon in the fields, the conversation turned political — and his pal suddenly turned against Hou, calling him a “Mainlander pig” and telling his friends not to speak to him.

In China, however, Hou was still an outsider as a “Taiwanese compatriot,” and even at the Tiananmen Square protests, he recalls being ostracized by some. During the hunger strikes and negotiations with the military, Hou says he just did what he was told to do — as a guest, he did not feel the right to be too proactive and opinionated.

Hou was part of the “campus folk” movement of the 1970s, and the first song he sold, Catch the Loach (捉泥鰍), is still a children’s classic. The 1978 Descendents of the Dragon (龍的傳人), which expressed pride in being Chinese, was a huge hit in both Taiwan and later China. He wrote it in response to the US severing relations with Taiwan, and intended for it to lament the plight of the Chinese and express his hope for them to be strong again. It was one of the songs sung in unison during the Tiananmen Square demonstrations, and it gained newfound popularity when Wang Leehom (王力宏) covered it in 2000.

That song is not as popular today due to the shift in the political climate and rise in Taiwanese identity, but most people can probably recite the chorus to Any Empty Bottles for Sale?, which was the theme song for the 1983 movie Papa, Can You Hear Me Sing? (搭錯車). It was remade into a musical in 2018, most recently shown in Taipei last November.

MOTIVES FOR LEAVING

Hou writes that former Government Information Office head James Soong (宋楚瑜) added a few propaganda lines to his song during a speech to military recruits, and his office later pressured the record company to re-record it with the new words. Hou refused.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t like Mr. Soong’s lyrics, or that I didn’t agree with them … I just didn’t want to become a propaganda tool,” Hou writes.

This led to some public backlash against his song in an era where patriotism was top priority.

Hou was later invited to pen a song for the Alliance for China’s Reunification under the Three Principles of the People (三民主義統一中國大同盟), and his friends urged him to accept the offer for the sake of his future. Hou writes that he was struggling financially at that time as he was notoriously difficult to work with.

“I didn’t have the courage to directly refuse them, but I decided to temporarily leave Taiwan,” he writes. “This was not the root cause of why I went to China, but why I began considering leaving.”

In May 1983, Hou headed to Hong Kong to promote his first album, which wasn’t selling well. By early June, he was in Beijing. He was branded a traitor and his songs were banned in Taiwan until martial law was lifted in 1987.

Some question the true motives behind his decision, as censorship and government bureaucracy in China was even worse there. Hou eventually ran afoul of a high-ranking official, who caused him much headache for the next few years; he was even undocumented for a while and was unable to earn any money.

THE PROTESTS

Hou watched the Tiananmen Square demonstrations unfold in 1989. To him, he writes, they were less about democracy, more about “speaking out against one’s dissatisfactions, resisting oppression and breaking free of all shackles.”

Shortly after returning from performing at the Concert For Democracy In China in Hong Kong, Hou was invited by Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波), Gao Xin (高新) and Zhou Duo (周舵) to join their hunger strike on June 2. The situation began worsening the following day, and when the news of troops killing demonstrators around Tiananmen made it to the monument where they sat by June 4, the four decided to evacuate the square.

As a celebrity, Hou helped negotiate with the troops to let the students leave in peace, and writes that he tried hard to convince the students to save their own lives. He watched the last group leave and later sought refuge at the Australian embassy. In August, he told an international documentary crew that he did not personally see anybody get killed within the square. He is often vilified for his comment, but insists that he was just telling the truth.

Gao corroborates this claim in a testament published in 1990 by the Washington Post: “Just as no one needs to exaggerate, or try to alter the fact that there had been huge, bloody confrontations outside the square in other parts of Beijing, it is also a fact that there was no one killed in the square.”

Hou remained in Beijing until May 1990, when he, Gao and Zhou wrote an open letter to the government, calling for the release of Liu and other protestors. The day before the letter was presented, Hou was arrested and given the choice of either going to jail or returning to Taiwan.

The authorities assured him that they would handle all technical issues on the Taiwan side, and several days later escorted him home to pack up. On the morning of June 18, Hou was put on a coast guard boat, which transferred him to a Taiwanese fishing vessel that night. Only then did he find out that the Taiwanese authorities knew nothing about his arrival, and that he was about to face charges of entering illegally.

After going home to see his family, Hou turned himself in. His return received widespread media coverage, much of the opinion of him unfavorable. He eventually left for New Zealand, but in 2011 he surprised the public again by appearing in Beijing and singing Descendants of the Dragon at the Bird’s Nest.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of