One might wonder why an exhibition about time would be in a railway museum, but as one display states: “Passengers must board the train on time, and operators need to know the exact position of each train at every moment. As the frequency of trains got denser and the division of time became more exact, the idea of ‘punctuality’ became a necessity.”

But the fascinating “Debating Modern: Inscription of Time (異論現代:銘刻時間)” display at Taipei’s Railway Department Park (鐵道部園區) is more than just about trains. The exhibition details how the concept of time took root and evolved in Taiwan during the Japanese era, and how it permeates every aspect of our lives in ways we might not think of.

For example, one section details how the idea of “free time” gave rise to tourism, which in turn led to the development of mountainous areas, disrupting the rhythm of life for the indigenous inhabitants that was already eroding from colonialism.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

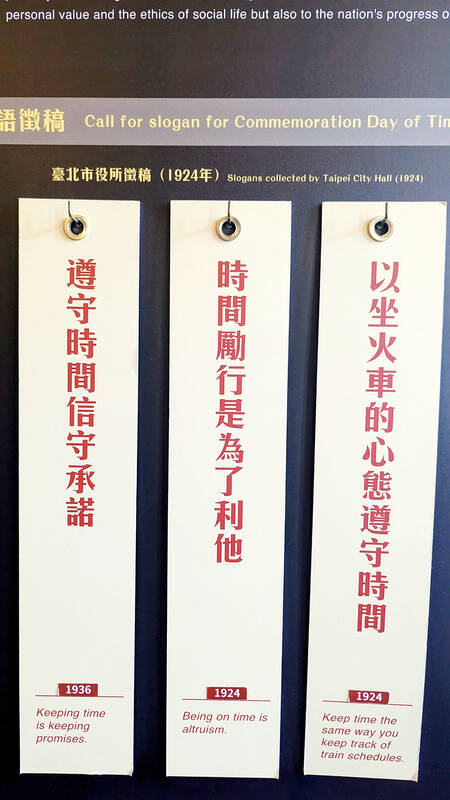

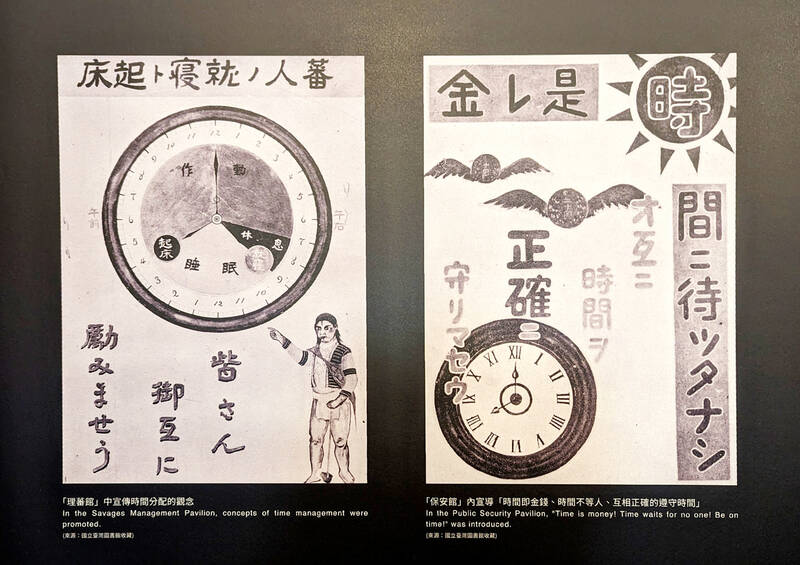

The exhibition occupies two rooms of the historic complex, the first tracing how indigenous people told time through changes in their natural environment, to how the Japanese colonizers instilled a sense of standardized, mechanized time into society that was synchronized with that of Japan. Early methods of reminding the public included the firing of “noon cannons” and regular morning calisthenics broadcasts. Curious items such as a chart dictating the daily schedule of indigenous people are displayed (wake up at 4am, work until 7pm, rest until 9pm and sleep), as well as entries from a punctuality slogan contest to mark “Time Commemoration Day.”

“A society which doesn’t not value time ultimately fails,” one warns.

The most creative part is the “24 Hours in Taipei” display, which follows a typical day in the capital during the 1930s to highlight interesting developments in the urban social fabric as routine schedules took hold. From the morning markets to office workers taking their mid-day break in a park to the burgeoning nightlife, time drove everything forward.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

This section goes beyond just describing what happened during certain hours, it also looks through historic texts and novels to delve deeper. The part on markets includes a news article on people climbing into the Central Market to clash with city staff who dictated that other markets follow their opening times, and the park section features an excerpt from a novel about unemployed men who gather in a corner of the park at noon to “experience the entertainment of the leisure class.” It’s a clever way to organize a large amount of information about varying topics in a succinct and easily digestible way.

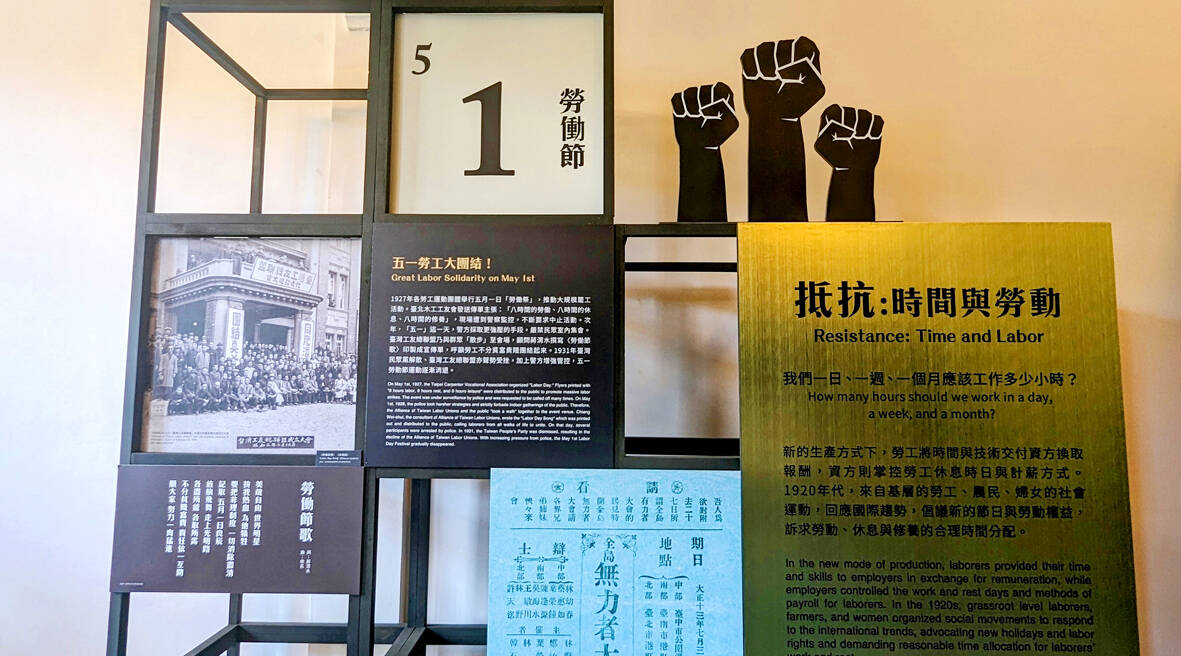

As mentioned earlier, the strictness of time gave rise to the demand for “time off.” In 1935, a women’s magazine published a piece by housewife Toyoko Shibata detailing the rigors of her 14-hour schedule with no respite as she has to watch the children on weekends. “Housewives need a day off too,” she laments. The next section, “Shapes of Time,” looks at the different meanings people assign to time, beginning with labor protests for better working hours.

It’s surprising to see that as early as 1927, laborers took to the streets on International Workers’ Day, as they still do today, to demand “eight hours work, eight hours rest and eight hours leisure.” Holidays, anniversaries, annual observances and debate over the use of different calendars are discussed here.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The most memorable part of this section, however, is a series of daily schedules without any extra information on them; the viewer can guess who it was designed for. For example, who gets up at 6:30am everyday, only gets 10 minutes of outside activity time every two days after lunch, and must go back to their room by 4:50pm? Lift up the schedule to find out the answer.

The end of the show abruptly transports visitors back to the present, with all of its modern conveniences, positing one final question: “Has technological progress brought more ample and quality time?”

FORESTRY HISTORY

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The other special exhibition at Railway Department Park on forestry railways is also worth checking out. The smell of cypress is noticeable even before one enters the room, and this is a more information-based overview of Taiwan’s forests, the development of its forestry industry and the railways constructed to transport timber down from the mountains during the Japanese era.

The first part is a bit text-heavy, but the next room provides visualizations of the various ways humans managed to move the giant trees of Alishan to the plains, showing different route designs and transportation methods such as aerial cableways. There’s a tiny model where visitors can experience how two train cars carrying a large log can traverse a bend, and a cable car that simulates a ride over the wooden landscape.

Personal stories from the workers can be found, as well as captivating scenes from daily life in the logging camps, including weddings, school activities and religious ceremonies. One image that stands out is a color photo of a worker performing a Zhongyuan Pudu (中元普渡) ceremony complete with a flayed pig on the train tracks.

The tale starts with the local indigenous people, whose traditional ways of life were severely impacted by these activities, and it concludes with a modern photo of Tsou elders blessing the reconstruction of the Alishan Forest Railway’s tunnel 42, which collapsed due to Typhoon Morakot in 2009 and Typhoon Dujian in 2015. The tunnel is for tourism, and unlike when the railway was built 110 years ago, the Tsou people participated in the planning and hope to benefit economically from it.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the