On the opening night of the Cannes film festival the guests gather for the premiere of Jeanne du Barry, a historical romp. It is the tale of a courtesan (played by the film’s director, Maiwenn) who catches the eye of a libidinous king and thereby flies in the face of propriety and good taste. The palace, we learn, is a place thick with intrigue, byzantine protocols and ridiculous rules that make no discernible sense. “It’s grotesque,” says one character. “No, it’s Versailles,” says another.

The royal court has its troubles — and so too does Cannes, where the traditional grand unveiling was all but derailed by the arrival of Johnny Depp, a Hollywood star dogged by allegations of domestic abuse whose performance as King Louis XV is his first leading role in a little over three years. Most critics were outraged but the festival was unmoved. Cannes shrugs off cancel culture and tends to lean into a fight. It figures that controversy is good for business and keeps us all on our toes.

“I first came to Cannes in 1992, accidentally,” Depp told reporters after he had toured the red carpet. “And it was an absolute circus like nothing I’d ever seen. And it remains that today — which is a good thing, I think.”

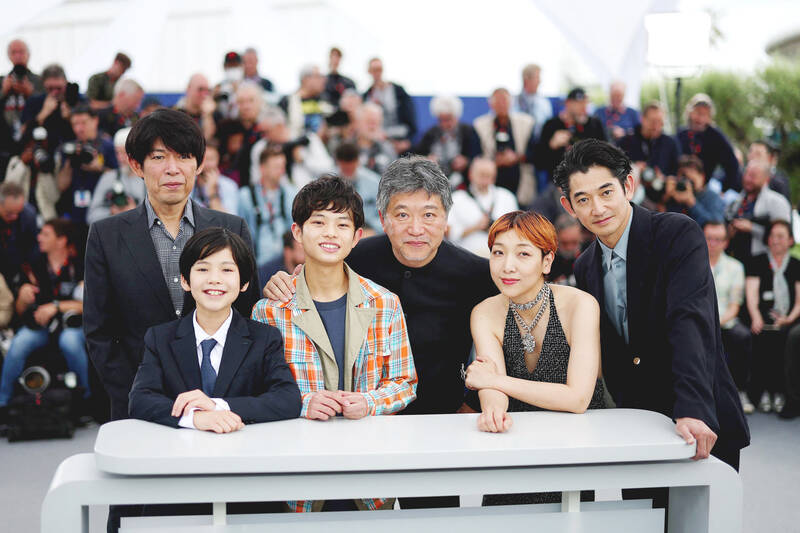

Photo: Reuters

If we applaud complexity in our films, why shouldn’t we require that of our film festivals, too?

Peer from one Croisette balcony and the place is a palace. Peer from another and it’s Barnum and Bailey’s big top, with all of the clowns falling out of their car and the elephant dung piled high, center stage. Some people detest it, which is a perfectly valid response, because it’s chaotic, enraging and wilfully perverse. But it is also bracing and challenging and quite often sublime. I love it, I hate it: sometimes within the same breath. It’s always struck me as amusing that Cannes once clutched its pearls and kicked out Lars von Trier. If Von Trier were a festival, he’d be this one right here.

The first days are a gallop. The guests are toiling to keep pace. The schedule seems at pains to cater to every taste, every time frame. Those with a spare four hours on their hands can immerse themselves in Steve McQueen’s Occupied City, a monumental, cross-cutting portrait of Amsterdam which shows the ghosts of the war years still haunting the canalside streets and picnic spots of today. Those on a stopwatch are better served by Pedro Almodovar’s Strange Way of Life, a 30-minute queer western. Dancing in the shadow of Brokeback Mountain, this casts Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal as ill-starred lovers in the one-horse town of Bitter Creek.

Photo: AP

This year’s jury president is the Swedish director Ruben Ostlund, a two-time Palme d’Or winner for 2017’s The Square and 2022’s Triangle of Sadness. He tells me that Cannes is unique in the way it’s able to balance both sides of the industry: the multiplex and the arthouse, the large with the small.

“So you have this big commercial presence here on the Croisette. But then you also get the small Iranian film shot on a cheap DV camera — and the organizers will give it the exact same amount of attention.”

No doubt Ostlund’s right. A random glance at the program throws up some wild juxtapositions. On the first Friday, for instance, blockbuster fans happily fill their boots at the premiere of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, in which 80-year-old Harrison Ford prepares to join battle with a band of ex-Nazis. Anyone requiring a more shaded and troubling film on a similar subject, though, would be advised to beat a path to Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, a romantic drama that incongruously plays out on the edge of Auschwitz. Turn one way, you’re in heaven. Turn the other, it’s hell.

First off the rank in hunt for the Palme d’Or comes Catherine Corsini’s Homecoming, a decent bantamweight contender, uncovering buried family trauma on the island of Corsica. It’s crisply performed and engagingly handled, gently tackling themes of gender, race and class politics. All the same, I fear that Corsini’s picture may finally be too tasteful and underpowered to properly trouble the judges.

Monster, meanwhile, boasts a robust constitution. Hirokazu Kore-eda’s film hinges on an altercation between a troubled student and a callow schoolteacher; an event that quickly threatens to consume everybody involved. But having initially established the crisis, Kore-eda pulls back; repositions. He frames the action from the perspective of the mother, the child and the teacher, so that his intimate human drama takes on the properties of a procedural thriller. Who’s lying, he’s asking. What is the real story here? Monster is at its most powerful during its fraught opening half, when we’re lost in the thicket, trying to make out the woods from the trees. Arguably it becomes less charged and successful when it belatedly steps in to explain. Sometimes the great mysteries are the ones that remain unresolved.

Out on the press terrace, writing this piece, I’m waylaid by an amiable, wiry man by the name of Sy Sabata. Sy explains that he’s of Romany heritage and a former Mr Universe, in town to raise funds for a big-screen biopic. He’s come to discuss the project with a Norwegian producer but he’s not exclusive and besides, the deal’s not yet set in stone. He sizes me up and makes a snap decision. He says: “Would you like to write the story of my life?”

I’ve covered Cannes for years and I still can’t pin it down. Great movies reveal fresh layers of mystery every time we see them. The best characters surprise us; that’s what makes them so compelling. And if we applaud complexity in our films, why shouldn’t we require that of our film festivals, too? Screenings thunder by like stampeding wildebeest on the plain. The scrum is so thick, I’m smelling 10 different armpits. This event contains multitudes. It contradicts itself and keeps going. It’s dreadful and it’s gorgeous. It’s grotesque, it’s Versailles.

A white horse stark against a black beach. A family pushes a car through floodwaters in Chiayi County. People play on a beach in Pingtung County, as a nuclear power plant looms in the background. These are just some of the powerful images on display as part of Shen Chao-liang’s (沈昭良) Drifting (Overture) exhibition, currently on display at AKI Gallery in Taipei. For the first time in Shen’s decorated career, his photography seeks to speak to broader, multi-layered issues within the fabric of Taiwanese society. The photographs look towards history, national identity, ecological changes and more to create a collection of images

In 2020, a labor attache from the Philippines in Taipei sent a letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanding that a Filipina worker accused of “cyber-libel” against then-president Rodrigo Duterte be deported. A press release from the Philippines office from the attache accused the woman of “using several social media accounts” to “discredit and malign the President and destabilize the government.” The attache also claimed that the woman had broken Taiwan’s laws. The government responded that she had broken no laws, and that all foreign workers were treated the same as Taiwan citizens and that “their rights are protected,

A series of dramatic news items dropped last month that shed light on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) attitudes towards three candidates for last year’s presidential election: Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲), Terry Gou (郭台銘), founder of Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密), also known as Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), and New Taipei City Mayor Hou You-yi (侯友宜) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It also revealed deep blue support for Ko and Gou from inside the KMT, how they interacted with the CCP and alleged election interference involving NT$100 million (US$3.05 million) or more raised by the

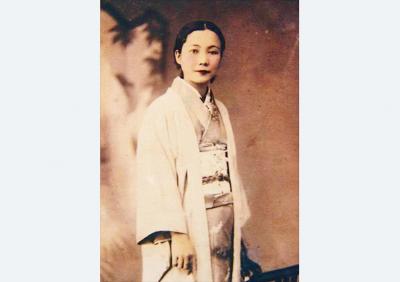

March 16 to March 22 In just a year, Liu Ching-hsiang (劉清香) went from Taiwanese opera performer to arguably Taiwan’s first pop superstar, pumping out hits that captivated the Japanese colony under the moniker Chun-chun (純純). Last week’s Taiwan in Time explored how the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) theme song for the Chinese silent movie The Peach Girl (桃花泣血記) unexpectedly became the first smash hit after the film’s Taipei premiere in March 1932, in part due to aggressive promotion on the streets. Seeing an opportunity, Columbia Records’ (affiliated with the US entity) Taiwan director Shojiro Kashino asked Liu, who had