The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests were one of the biggest news stories of its era, but it was global real-time coverage that arguably gave the story its massive impact. And this was the result of an unexpected quirk of history.

Less than a month before the June 4 crackdown, from May 15 to 18, China had arranged a historic summit with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in Beijing. The meeting represented an historic rapprochement between the two communist superpowers after the relationship deteriorated badly during the later Mao Zedong (毛澤東) years.

China was eager to show off the meeting to the world and the international press was just as hungry for the story. So beginning in April 1989, China began granting unprecedented access to Western media, just as the student democracy movement was beginning to unfold.

In April and May, Government ministries directly assisted CNN and other networks in setting up satellite feeds to beam images from the rostrum on the Gate of Heavenly Peace in an era when live TV still required considerable advance preparation. China also issued scores of journalist visas, including 57 visas to just a single US network, CBS.

But when the US networks began filming on May 15, Gorbachev’s official reception had to be moved to Beijing’s airport and reporters saw “that the students had literally occupied the stage where Chinese leaders were to welcome Gorbachev,” recalls Mike Chinoy, then CNN’s Beijing bureau chief.

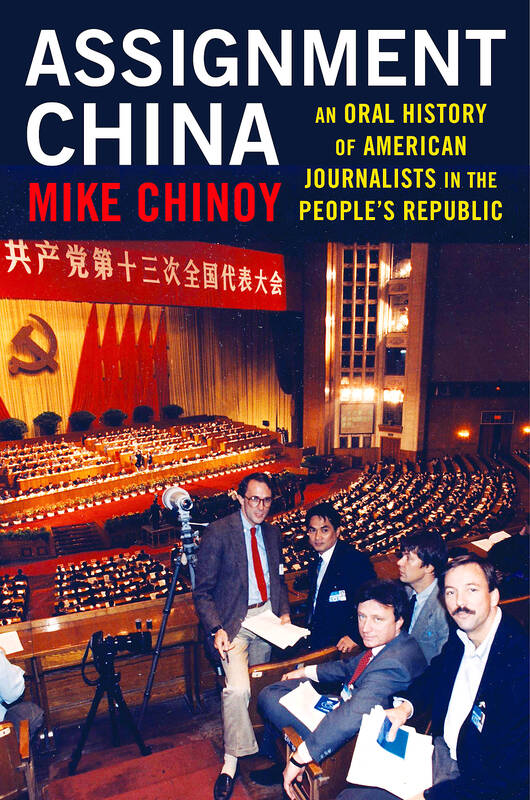

In a new book Assignment China: An Oral History of American Journalists in the People’s Republic, Chinoy relates this and other inside-the-media stories, offering a systematic account of more than 80 years of covering China. A fantastic read, the book is nothing short of a news junkie’s fantasy.

Beginning with freewheeling war correspondents running between communist and Nationalist armies in the civil war of the 1940s, the book moves on to describe “China watching” from Hong Kong during the Cold War years, the first Beijing bureaus following the resumption of formal diplomatic ties between the US and China in 1979, and the first ever one-on-one television interview with a Chinese leader — Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平) on the CBS news program 60 Minutes — in 1986, and other major firsts and trends of China coverage. Accounts continue right up through the appearance of female and Chinese-American reporters in a more inclusive, post-1990s press corps and on to COVID-19 and China’s recent 2020 expulsions of Western journalists.

These stories come directly from the mouths of top China correspondents, which were captured by Chinoy in more than a hundred video-taped interviews. They include major TV news personalities like Dan Rather, Ted Koppel and Diane Sawyer as well as generations of in-the-trenches reporters from the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal and major wire services.

Chinoy’s goal with this record is to lay bare the processes of how news from China has been covered, and also how the media itself became an active player in unfolding events.

‘CNN EFFECT’

Tiananmen coverage, he contends, was a major turning point in the dynamic of news as a driver of policy. As fresh reports of the Tiananmen massacre were hitting TV screens around the world, CNN interviewed US Secretary of State James Baker on air and asked him point blank if unfolding events would prompt a US reaction. Baker was caught off guard and later said, “Tiananmen was the first example of… the power of media to drive policy,” and “there’s no doubt this was the first example of this phenomenon.”

This trend became known as the “CNN effect,” which CNN anchor Bernard Shaw explained saying “reactions and decisions are made based on events as they’re happening in real time.”

Unlike Tiananmen, not every big China story was able to reach international audiences. In January 1976, Chinoy was in Hong Kong working for CBS news radio when a massive earthquake in the Tangshan region, 175km east of Beijing, was believed to have killed almost a quarter of a million people. Despite the disaster’s staggering scale, few photos and no video of the disaster ever surfaced, so the story barely registered internationally.

“I recall going every day to the Hong Kong train station to meet trains coming from the mainland in a fruitless effort to find a foreign traveler who might have taken some home movies,” wrote Chinoy. But his search was fruitless, and the story remained underreported.

SPONTANEITY VS CONTROL

The big picture one finds in Assignment China is a constant oscillation of tightening and loosening, a cat and mouse game between Chinese officials and Western reporters. As early as the 1970s during Nixon’s first visit to China, CBS News producer Irv Drasnin noted a fundamental difference between the two societies: “We believe in spontaneity. The Chinese believe in planning. We want to discover reality, get as close to it as we can. The Chinese want control,” he said.

Often what drove the restrictions were perceived losses of face by the Chinese leadership when Western media revealed embarrassing truths about poverty, repression or corruption. As early as 1973, Canada’s Globe and Mail correspondent John Burns was summoned to China’s Foreign Ministry for the familiar rebuke, “You have insulted the leadership of the People’s Republic of China!”

One is also struck by stories of iconic scoops and images that might have never made it to press. Images of Tiananmen’s famous “tank man” were only captured by two sources, but by that time all the Western networks’ live feeds had already been shut down by Chinese authorities and soldiers had been instructed to shoot anyone on the streets with a camera. The photo of the scene by AP photographer Jeff Widener, still on a roll of film, was carried in the underwear of a foreign exchange student across town to the satellite link at the AP office. CNN’s video tapes were meanwhile sent to Beijing’s airport and smuggled to Hong Kong by a tourist.

The book contains only a few oblique mentions of Taiwan. The first of these is the friendship between Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and Time-Life founder Henry Luce, who was Chiang’s greatest publicist. In the early 1950s, Time reporter Stanley Karnow sat in on a dinner interview between Luce and Chiang at Taipei’s Grand Hotel and described it as “absolutely idiotic.”

Chinoy also describes the 1972 Shanghai Communique –– which established the “one China” policy that continues to determine America’s official view of Taiwan as a non-nation –– as rushed out in deep secrecy by only two men, US National Security Advisor Henry Kissenger and President Richard Nixon, who believed it was a diplomatic coup and could only be pulled off by circumventing the entire State Department. Many historians however argue Nixon was hoodwinked in the deal, a sentiment summed up at the time by a headline in the Detroit Free Press: “They Got Taiwan. We Got Eggrolls.”

Assignment China is packed full of such wonderful anecdotes, all delivered in conversational speech of reporters on the scene, state department officials and Chinese government personnel. I found myself tearing through the pages. For the modern China bookshelf, this is absolutely required reading. But even for casual news watchers, it’s a highly accessible and utterly engrossing history. It’s never less than fascinating the way Chinoy pulls back the curtain on how the news was reported from China.

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions

There is a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) plot to put millions at the mercy of the CCP using just released AI technology. This isn’t being overly dramatic. The speed at which AI is improving is exponential as AI improves itself, and we are unprepared for this because we have never experienced anything like this before. For example, a few months ago music videos made on home computers began appearing with AI-generated people and scenes in them that were pretty impressive, but the people would sprout extra arms and fingers, food would inexplicably fly off plates into mouths and text on

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

US President Donald Trump’s threat of tariffs on semiconductor chips has complicated Taiwan’s bid to remain a global powerhouse in the critical sector and stay onside with key backer Washington, analysts said. Since taking office last month, Trump has warned of sweeping tariffs against some of his country’s biggest trade partners to push companies to shift manufacturing to the US and reduce its huge trade deficit. The latest levies announced last week include a 25 percent, or higher, tax on imported chips, which are used in everything from smartphones to missiles. Taiwan produces more than half of the world’s chips and nearly all