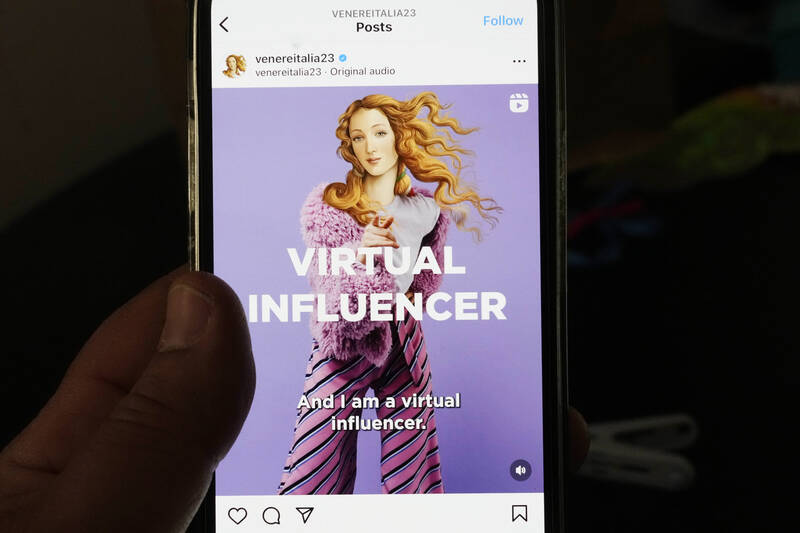

The Italian tourism ministry thought it had a sure-fire way to bring travelers into the country: turning a 15th century art icon into a 21st century “virtual influencer.”

The digital rendition of Venus, goddess of love, based on Sandro Botticelli’s Renaissance masterpiece Birth of Venus, can be seen noshing on pizza and snapping selfies for her Instagram page. Unlike the original, this Venus is fully clothed. The influencer claims to be 30, or “maybe just a wee bit (older) than that.”

But the new ad campaign is facing significant backlash — with critics calling it a “new Barbie” that trashes Italy’s cultural heritage.

Photo: AP

The tourist campaign “trivializes our heritage in the most vulgar way, transforming Botticelli’s Venus into yet another stereotyped female beauty,” Livia Garomersini, an art historian and activist with Mi Riconosci, an art and heritage campaign organization, said in a response to the project last month.

The yearlong campaign, produced by national tourism agency ENIT and advertising group Armando Testa, is estimated to have cost nine million euros (about US$9.9 million), according to ENIT CEO Ivana Jelinic.

Jelinic said that the campaign was designed for overseas markets to attract younger tourists. The online Venus launched in Italy on April 20 and made her international debut in Dubai at the Arabian Travel Market earlier this week.

Photo: AP

“We liked the idea that it would be a work of art that is timeless,” Jelinic said, adding that Botticelli’s Venus “seemed to us like a immortal icon who could represent Italy well.”

Already the new Venus has been memed mercilessly online, appearing among trash bins, alongside Mafia boss Matteo Messina Denaro and in other less-than godly places.

The criticism extends beyond the use of a masterpiece to the manner in which the campaign was orchestrated, including its use of stock images and other gaffes like a promotional video featuring a winery in Slovenia, used as a stand-in for Italy.

An even greater sin for many is the campaign’s slogan, “Open to Meraviglia” (Open to Wonder), because it mixes English into an Italian tourist campaign even as the country’s government seeks to protect the Italian language as a pillar of its culture.

There are other language faux pas.

On the campaign’s Web site, an automatic translator turned Brindisi, a southern Italian port town, into its literal English definition: “Toast,” according to Matteo Flora, a professor at the University of Pavia. That part of the Web site has now been obscured.

“Let’s not talk about the creativity point of view,” said Flora, “You may like (the campaign) or not, but on a technical point of view, it has been... a sort of avalanche of problems.”

That includes a failure to secure domains, allowing anyone to snatch the material and mock the project with it.

Flora said the campaign also wasted money. The campaign’s creative team chose to use the “intelligence of human creativity,” rather than artificial intelligence, to build the virtual Venus — but Flora showed how he could quickly come up with a similar campaign using AI at a cost of 20 euros. His social media posts have been shared by thousands of people.

The use of a likeness of Botticelli’s masterpiece has been lambasted by art historians as well, who say it vastly diminishes the beauty and mystery of the 15th century original.

“Perhaps Botticelli would not be happy about this,” said Massimo Moretti, a professor of art history at the University of Rome, Sapienza.

Any use of an iconic image like the Birth of Venus risks striking a cultural nerve, marketing experts say.

“The more you try to alter something that’s historic, probably the greater the outcry,” said Larry Chiagouris, professor of marketing at Pace University’s Lubin School of Business.

“People are going to say, ‘You’re changing the culture. You’re changing who we are, because it’s part of our history,’” Chiagouris added.

“I didn’t like the fact that they used the Botticelli Venus like that, since it is a piece of art,” Riccardo Rodrigo, a high school student in Rome, said. “They made it something social friendly to amuse Gen Z, I think it was unnecessary since it can be used just like it is and not modified like they did.”

The Uffizi Galleries, which houses Botticelli’s Birth of Venus in Florence, declined to comment on the campaign.

For the creators of the campaign, however, any press is good press.

“It has become so viral,” said Jelinic of ENIT, adding that “Web users have made her come alive” even when placing the new Venus in unglamorous places.

“I find (it) interesting in terms of social communication,” Jelinic said. “Our campaign is more appealing than (critics) want to admit.”

Tourism officials plan to expand the campaign through the use of billboards as well as video screens in airports and railways.

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled