Gerrit W. Gong, an Asianist who held many positions in universities and the US government, once said that “The Cold War’s thaw brought not an end of history, but its resurgence.” What Gong forgot to add was that resurgent history was in no small part expansionist fantasy.

During the 1930s, it was well established in Chinese minds that Taiwan lay outside of China. The thinking behind Mao’s famous comment that the Koreans deserved help breaking the chains of Japanese imperialism, as did the Taiwanese, was widely echoed across both Communist and Nationalist elites and was transmitted by them to the young.

Today we know terms like “united front” in the context of Chinese imperialism and expansionism, but in the 1930s the term had another meaning: it encapsulated the desire of Asians struggling to form a “united front” against external imperialism. Lan Shi-chi (藍適齊) identifies several publications aimed at Chinese youth in the 1930s that forwarded this concept (“The Ambivalence Of National Imagination: Defining ‘The Taiwanese’ In China, 1931-1941,” The China Journal, No. 64, July 2010).

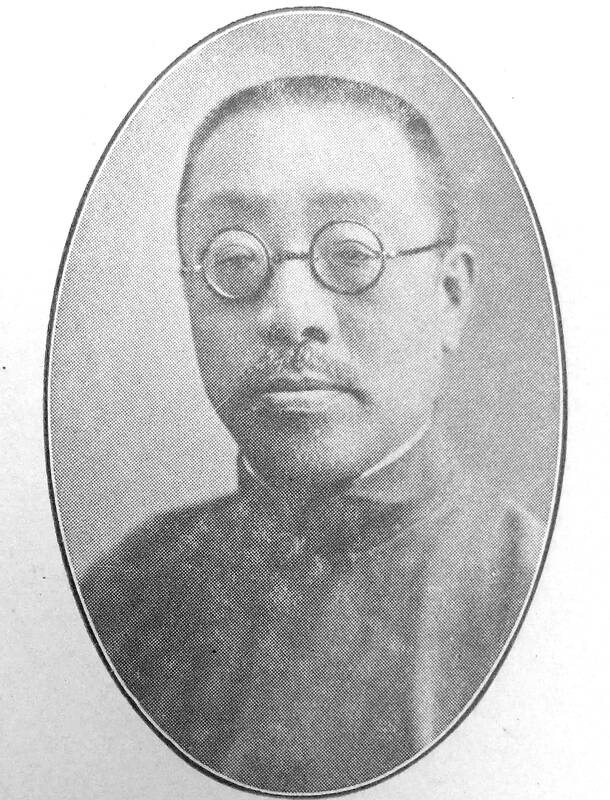

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

For example, Lan observes, a book aimed at young people entitled The Issue of Weak and Small Nations of the World had 14 chapters describing different nations, including Taiwan. Lan quotes the text as saying that Chinese may have forgotten the day they lost their nation, “but the Taiwanese will never forget (it) unless (their) nation is liberated (and) their independent autonomy movement succeeds.”

Another book series Lan instances discusses national liberation movements around the world. It locates Taiwan among its examples of national liberation movements in Asia, and says of Taiwan’s activities against Japanese rule since 1895 that: “… these national liberation struggles were all pointing their spears against Japanese imperialism and fighting for Taiwan’s independence and freedom.”

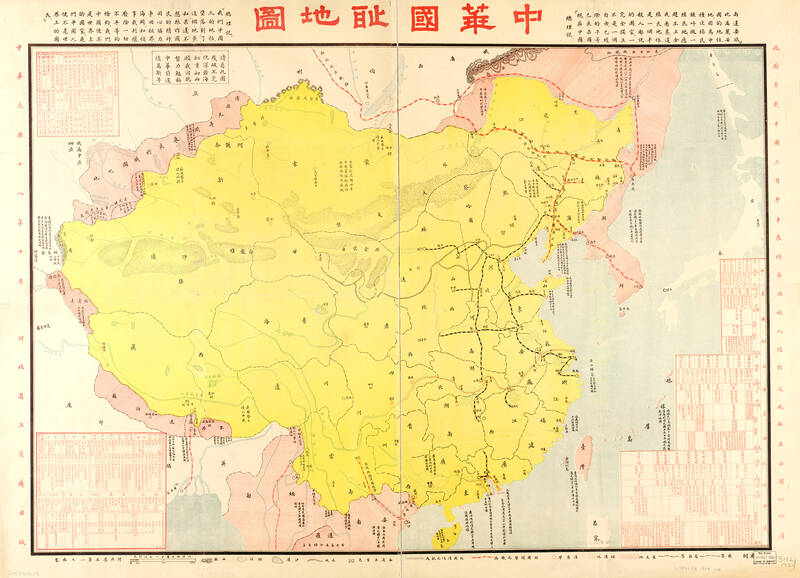

MAPS OF HUMILIATION

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

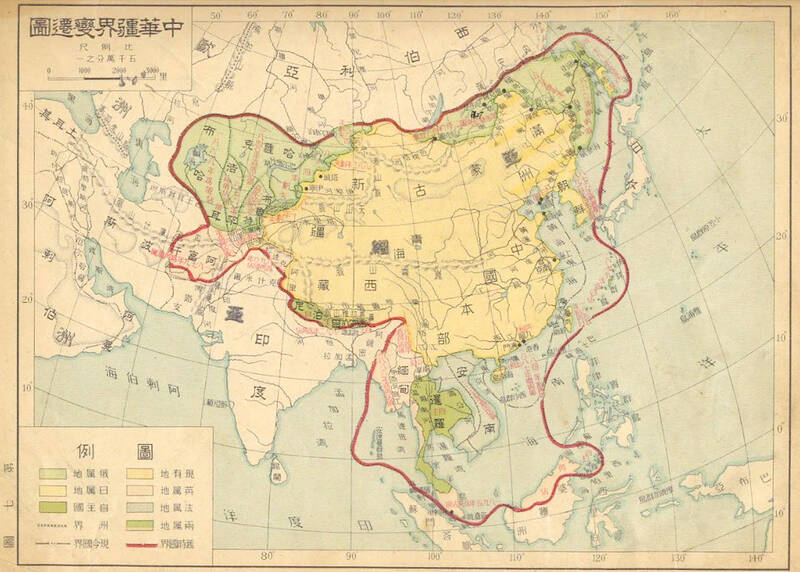

At the same time as elites were following a long tradition of mentally locating Taiwan outside China, a burgeoning private movement to get elites to see China’s borders as both expanding and expansive was occurring. According to scholar and research Bill Hayton, cartographer Bai Mei-chu (白眉初) began developing the existing idea of “maps of national humiliation” (國恥地圖), which purported to show territories “lost” to China.

These maps represent expansionist fantasies in cartographic form. Depending on the mapper, they might show that all of Siberia, or Malaysia, or Thailand and many other places in Asia are territories that China once owned, but have now been lost. Simply searching the text string in Chinese above will turn up many examples of them, including some apparently used in classrooms in the late 1930s.

These maps showed a Chinese world that resembles, in many ways, the expansionist ideology contained in the phrase “Russkiy mir,” familiar since the Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine.

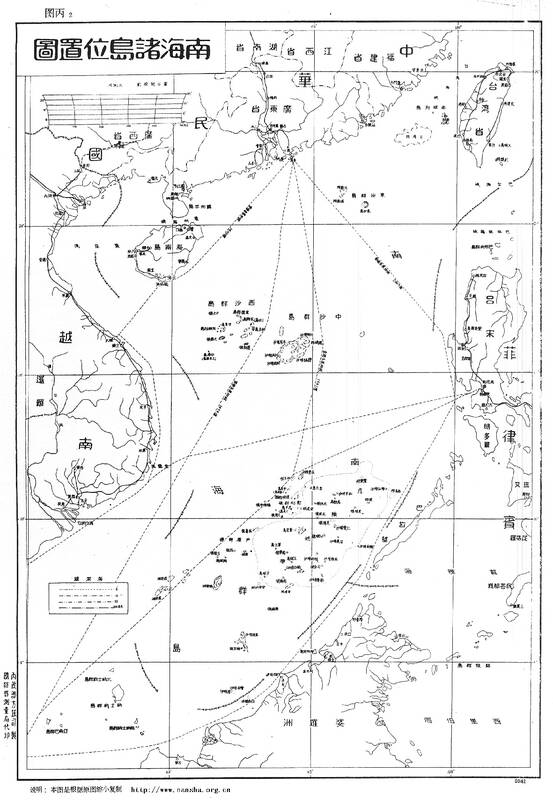

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Bai drew a line around the South China Sea and declared that it was lost territory. It was completely unknown to the Manchus, whose imperial borders ended at Hainan Island until 1900. As Hayton notes, in 1909 the governor of Guangdong Province sent a boat out to the Paracel Islands (Xisha Islands, 西沙群島) but because no Chinese pilot knew the area, they had to borrow German captains from a local trading firm. The islands finally appeared on Manchu maps that same year.

The first Republic of China (ROC) map was issued in 1912. It showed not only Taiwan but also northern Vietnam and Korea as “lost territories” awaiting return, and its borders were not defined. In fact, the term “renegade province” was originally used largely in southern China to refer to north Vietnam. It was applied to Taiwan later, and by outsiders first.

As Lan notes, it was Korea, not Taiwan, that was “usually represented as more significant to the Chinese and China as a nation than were the Taiwanese.” He examples the patriotic song “Ten Great Hatreds,” (十大恨) which said that the worst pain inflicted by the Treaty of Shimonoseki was the war indemnity paid to Japan, followed by the independence of Korea. Only then did Taiwan appear.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

INFAMOUS LINE

In the 1930s, even as Chinese elites were making comments about Taiwan’s independence and separateness from China that later Taiwan independence supporters would seize on, another strain of imagining was taking hold of China. Bai’s lines were taken up by other commentators, and eventually, the state. Late in 1946 the ROC would issue the first of the infamous 11-dash line maps showing that the South China Sea belonged to China.

Chinese interest in the South China Sea was stimulated by France’s move to grab the islands there as part of French Indochina. The ROC, which had no idea of the islands’ existence, sent for maps from Manila. Hence, the early ROC maps simply use the English names for the islands since there were no official Chinese names. ROC cartographers were so clueless that subsurface features, such as James Shoal, were reimagined as islands.

This second strain of expansionist imaginings was largely a private sector initiative picked up by the government in the late 1930s. It was inherent in the decisions made late in the 19th century to inflate the next Han-led state out to the borders of the Manchu empire and redefine all the neighboring peoples as “Chinese.”

Prior to 1942, as Alan Wachman observed in Why Taiwan? Geostrategic Rationales for China’s Territorial Integrity, both the Nationalist and Communist leaderships were indifferent to Taiwan during the interwar period. This changed only after the US entered the war and Chinese elites began to imagine what they could grab after the war, including Taiwan.

Many centuries of Chinese thinkers somehow missing that Taiwan was a core Chinese interest thus came to a sudden end.

FALSIFYING HISTORY

This desire to annex Taiwan led to the deliberate falsification of history later in the war by the Nationalists to construct an argument for incorporating Taiwan as a Chinese holding, as Steven Phillips has chronicled in Between Assimilation and Independence: The Taiwanese Encounter Nationalist China, 1945-1950. The discourse that recast annexation as “return” would be taken up by the People’s Republic of China when it came into power, and further developed with new absurd claims, such as the idea that the Yizhou (夷洲) chronicled in a third century text was Taiwan.

The arbitrary nature of Chinese claims is also highlighted by the status of Mongolia. Lan points to Chinese government survey reports on Taiwan and Mongolia. The Mongolians, despite acknowledged differences in language and appearance, are nevertheless presented as Chinese. The Taiwanese, who could have been criticized for learning Japanese language and culture, were admiringly presented as foreigners who were benefiting from Japan’s modernizing hand, Lan observes.

The discourse of the Japanese as evil colonialists despoiling a Chinese province, causing its people to adopt independence thinking, is entirely a postwar invention.

This is the ultimate and tragic contingency of Taiwan’s history: Taiwan could have gone the way of Vietnam and Korea and been recognized by the ROC as an independent state. Japan’s imperial dreams died at Midway and Guadalcanal, and with them, the prospect of Chinese acceptance of an independent Taiwan.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she